YORKTON - It is always fascinating – at least to this writer – when a book about a sport such as baseball – is entwined with the broader history of the world around the game at the time.

In Yorkton This Week I recently wrote about one such book with The Gas and Flame Men: Baseball and the Chemical Warfare Service during World War I by Jim Leeke.

And now it’s another story of baseball again wrapped tightly in the story of WWI.

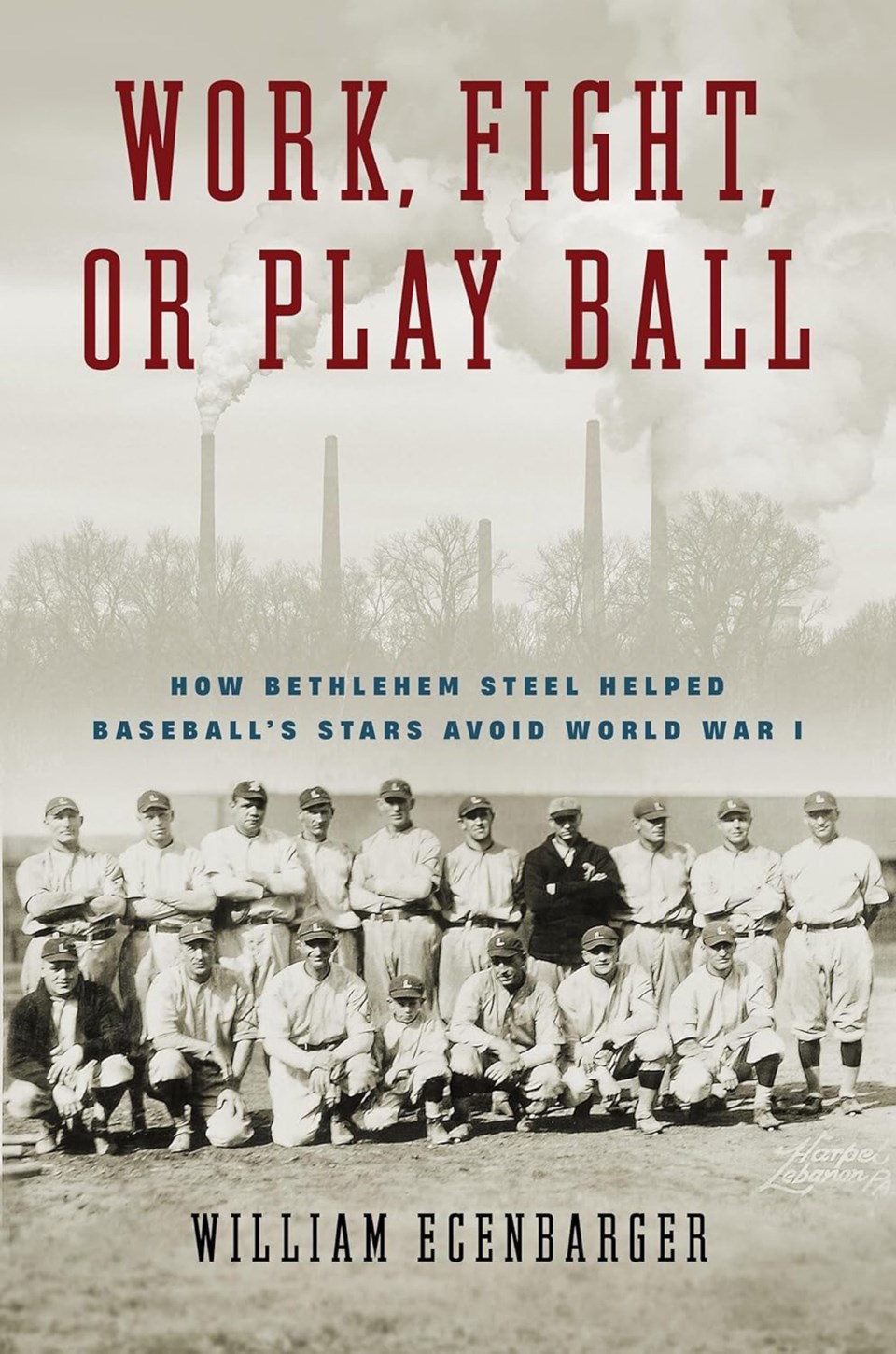

In Work, Fight, or Play Ball: How Bethlehem Steel Helped Baseball's Stars Avoid World War I author William Ecenbarger looks at the baseball leagues that emerged out of the steel mills and shipyards of the era.

Company-based teams and leagues weren’t new at the time, but because young men could avoid being conscripted to serve on the front by taking jobs that were deemed essential, many Major League players of the time were eager to take such jobs.

Of course most focused far more on playing baseball than smelting steel or building ships as companies sought the game as a diversion for workers, a way to make extra cash and of course garner glory.

From the publisher’s website (www.tupress.temple.edu); “in 1918, Bethlehem Steel started the world’s greatest industrial baseball league. Appealing to Major League Baseball players looking to avoid service in the Great War, teams employed “ringers” like Babe Ruth, Rogers Hornsby, and Shoeless Joe Jackson in what became scornfully known as “safe shelter” leagues. In Work, Fight, or Play Ball, William Ecenbarger fondly recounts this little-known story of how dozens of athletes faced professional conflicts and a difficult choice in light of public perceptions and war propaganda.

“Some players used the steel mill and shipyard leagues to avoid wartime military duty, irking Major League owners, who saw their rosters dwindling. Bethlehem Steel President Charles Schwab (no relation to the financier) saw the league as a means to stave off employee and union organizing. Most fans loudly criticized the ballplayers, but nevertheless showed up to watch the action on the diamond.

“Ecenbarger traces the 1918 Steel League’s season and compares the fates of the players who defected to industry or continued to play stateside with the travails of the Major Leaguers, such as Christy Mathewson, Ty Cobb, and Grover Cleveland Alexander, who served during the war.

“Work, Fight, or Play Ball reveals the home field advantage brought on by the war, which allowed companies to profit from Major League players.”

It’s a fascinating, albeit short-lived, piece of baseball history, one author Ecenbarger said he stumbled upon decades ago walking his dog.

“I used to walk my dog in an abandoned amusement park in Philadelphia,” he told Yorkton This Week.

As dogs tend to do, it pooped in an adjacent field, a field with a sign that said it was once the site of Babe Ruth Field.

Ecenbarger said he became curious calling the local historical society asking about the field noting Ruth never played in Philly.

But he had with one of the steel teams.

That germ of an idea was planted some 35 years ago, said Ecenbarger, adding “it stuck with me.”

Initially it was a long newspaper article written three decades ago, and Ecenbarger said at that point he never considered it might grow into a book.

“But, it was a really interesting story with a lot of big baseball starts involved,” he said.

The idea was shelved in his mind for years, but it was still there.

Ecenbarger has written other books, but not one on the game, and it was something he longed to do.

“I’m a baseball fan and I always wanted to write about baseball,” he said.

So last year he went back to the long held idea, and dug into the history in greater depth.

While the leagues are from decades ago, Ecenbarger said he found lots of information, most by digging into old newspapers.

“Number one back then baseball was the biggest sport at that time,” he said.

And it was the days before radio and TV.

“The only source was newspapers,” he said adding reports were detailed including things such as how many attended or who might of argued with an umpire that day.”

It was so much information Ecenbarger ultimately included many of the details in the book appendix rather than having too much game day detail within the main text.

That was good plan as the story could have bogged down under the weight of too much detail of games that were individually not the greatest interest of this book.

The book was one Ecenbarger said was a pleasure to create.

“This one was fun to write,” he said, adding “. . . Baseball’s a great game.”

Certainly, Ecenbarger’s passion for the game is evident here, simply by undertaking to write a book on a rather obscure piece of baseball/WWI history. It is the obscurity revealed here that makes this one worth reading at only about 165 pages.