WESTERN PRODUCER — Greg Stewart is different from most innovators in Canadian agriculture.

People that start ag companies are often plant scientists, agronomists or experts in farm machinery. Stewart has a master’s degree in applied mathematics from Dalhousie University and a PhD in control engineering from the University of British Columbia.

“A controls engineer ensures that an organization can create high-quality products in the most efficient manner possible,” says coursera.org. “There are many different types of control systems, but each one serves the same purpose: to control outputs.”

Stewart, who lives in Vancouver, has used his expertise in a range of industries, including pulp and paper, automotive powertrains, semiconductors and designing brakes for airplanes.

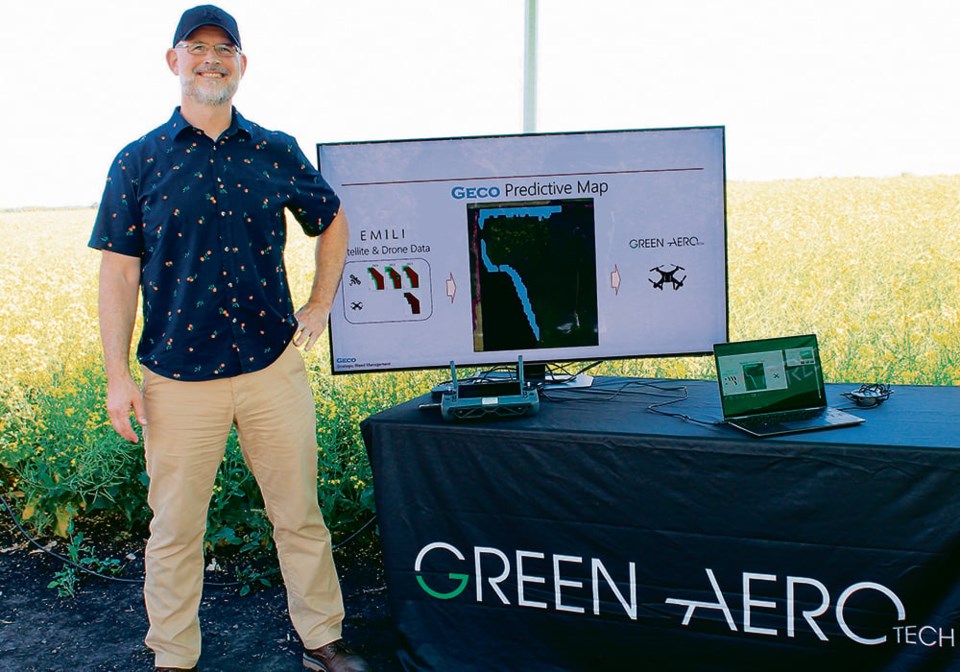

He is the founder of Geco Engineering, which has turned its attention to crop production.

“My passion is in developing and deploying advanced machine learning (or AI), control, and automation technologies … to address meaningful problems,” says his UBC profile page.

“I’m fascinated by the challenges and opportunities posed by agricultural problems.”

Right now, he’s focused on the problem of weed management.

Most farmers apply a single herbicide or multiple herbicides across an entire field to control weeds. Stewart has developed a technology that creates predictive weed maps so farmers can use herbicides more strategically.

“We’re making predictions about where weeds will emerge. The technology is a combination of AI (Artificial Intelligence) and agronomic modelling,” Stewart said. “We’re looking at what the weed population has been doing over the last five years… Then we’re able to make a prediction about where they will appear next year.”

Stewart’s technology is different from spot spray, where cameras on a sprayer boom can detect a weed and apply a precise shot of herbicide.

Geco’s predictive model relies on satellite images of a field and uses those images to calculate where weeds will likely appear.

“You (can) get maybe 250 images (per year) that you can use,” he explained. “The cost is very cheap. It’s historical data. And it’s on 100 percent of the farms.”

A single, satellite image of a wheat field in southern Saskatchewan isn’t that helpful, because it’s very difficult to see the weeds. Geco’s machine learning technology relies on dozens of images of that field.

“If you could take the satellite images over an entire growing season, then you could parse out what is a weed and what is a crop,” said Stewart.

Geco uses five years of satellite images to predict where weeds will grow. If the weed prediction map is for 2024, it would rely on images of that field from 2019-2023.

The prediction map is converted into a file and uploaded to a sprayer equipped with GPS.

“From there, it automates the process,” Stewart said.

“As the sprayer moves around the field … it will drop herbicide on the areas where we (are predicting weeds) and will put none on the areas where we are predicting there won’t be weeds.”

Stewart said the technology is suited for soil applied herbicides, possibly a granular product.

“Someone will put down a soil applied herbicide … either in the fall or in the spring. The weeds are not yet germinated and they (farmers) want to know where to put this stuff down,” said Stewart, who has also developed technology to predict when diseases will appear in greenhouse crops.

A soil-applied herbicide introduces another mode of action, reducing the likelihood of herbicide resistant weeds. However, the products are relatively expensive.

“As a result, farmers are reluctant to use them,” Stewart said. “If we could cut down the per acre price by 50 percent (by targeting the areas that need it), that suddenly becomes more feasible.”

Predictive weed maps could be used to:

- Apply the same herbicide across the field but with higher rates where weeds are likely to appear; and

- Add another chemistry and spray the additional product on potential weed hot spots.

Geco has been testing its technology north of Winnipeg at Innovation Farms, a 5,500 acre smart farm managed by EMILI, a non-profit with a mandate to help Canada become a leader in digital agriculture.

Agronomists and technicians have used drones and satellites to collect imagery on kochia and wild oat as part of the Innovation Farms collaboration with Geco.

Stewart has also processed satellite images from 24 farms across four provinces.

“Somewhere between 30-40 individual fields,” he said.

The predictive weed model will improve with more data so it can accurately predict the emergence of different weed types in different crops.

As for the Geco business model, the company will charge farmers a fee per acre, or likely offer a subscription for the weed prediction service.

Stewart plans to attend farm shows across Canada this winter to spread the word about Geco and its weed prediction technology.

Bookmark SASKTODAY.ca, Saskatchewan's home page, at this link.