CANORA — It's one thing to observe Truth and Reconciliation Day. It's something quite different to actually learn what happened to residential school students.

Canora Composite School students completed an array of projects including artwork, individual projects, posters, song writing, and novel studies in the week leading up to Truth and Reconciliation Day (Sept. 30).

“I learned we had to acknowledge what has happened in the past in order to come to peace with each other," said Meekah Unick, Grade 9.

CCS Staff members made bulletin boards, read Truth and Reconciliation books to their classes, and introduced lessons on reconciliation.

All students from Grade 5-12 attended a presentation on Truth and Reconciliation, led by Jennifer Bisschop, CCS library technician. Following is her presentation:

Residential schools

In Canada, the Indian Residential school system was a network of boarding schools for Indigenous peoples. Residential schools were established by the Canadian Government and administered by the Roman Catholic, Methodist, Anglican, Presbyterian, and United churches. The schools operated in Canada from 1831 to 1996.

During this time over 150,000 children attended the schools. Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their family homes and sent to live in these boarding schools, completely alienated from their families. The purpose of residential schools was to educate and convert Indigenous youth and to assimilate them into Canadian society.

Residential schools were underfunded and overcrowded; they were rife with starvation, neglect, and physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, often including isolation from normal human contact and nurturing. Students were forcibly removed from their communities, homes and parents, and frequently forbidden to speak their Indigenous language and perform traditional music and dance.Residential schools caused immeasurable damage, disrupting lives, disturbing healthy communities and causing long-term problems.

For more than 100 years, the Canadian government supported residential school programs that isolated Indigenous children from their families and communities. Under the guise of educating and preparing Indigenous children for their participation in Canadian society, the federal government and other administrators of the residential school system committed what has since been described as an act of cultural genocide. As generations of students left these institutions, they returned to their home communities without the knowledge, skills or tools to cope in either world. The impacts of their institutionalization in residential school continue to be felt by subsequent generations. This is called intergenerational trauma.

Unmarked graves

It is estimated that over 6,000 Indigenous children may have died at residential schools. Many of the children died from disease such as: tuberculosis, malnourishment, abuse, neglect, accident, suicide, drowning, or trying to run away.

Many of the children who died in residential schools were far from home. The long distances meant that families weren’t always notified when their children died. The official policy on burials was: "Ordinarily the body will be returned to the reserve for burial only when transportation, embalming costs and all other expenses are borne by next of kin.” Most indigenous families couldn't afford these costs. When children couldn’t be returned to their parents, responsibility for their burial fell to the schools, which didn’t always have the money to make proper funeral arrangements. Those that were given funerals were often placed in plots with no markers. These are the graves that are just being found now at former residential school sites.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission was officially established on June 1, 2008, with the purpose of documenting the history and lasting impacts of the Canadian Indian Residential School system on Indigenous students and their families. The Commission took six years and interviewed over 6,500 survivors of residential schools.

In 2013 the TRC made 94 calls to action. The calls to action are recommendations and improvements for such things as child welfare, education, reconciliation, youth programs, equity in legal system, museums and archives, etc. As of today only 17 calls have been completed.

Reconciliation

Webster's defines Reconciliation, “as to restore friendship or harmony."

Bisschop asked the students, "What does reconciliation mean to you?"

Here are some of the words the students came up with to describe reconciliation:“Respect, heal, education, friendship, listening, peace, kind, TRC, Canada, experiences, honour, fair, impact, future, improvement, relationships, apologize, acknowledgement, recommendations, knowing, harmony, culture, actions, participate, impact, knowing, history, share, change, learn, understand, aware.”

Truth and Reconciliation Day

The federal government recently passed legislation to make Sept. 30 a federal statutory holiday called the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

“The day honours the children who never returned home and survivors of residential schools, as well as their families and communities. Public commemoration of the tragic and painful history and ongoing impacts of residential schools is a vital component of the reconciliation process."

Orange Shirt day

Orange Shirt day is also Sept. 30 and was started By Phyllis Webstad in recognition of the harm the residential school system did to children's sense of self-esteem and well-being, and as an affirmation of a commitment to ensure that everyone around us matters. Orange shirt day is an opportunity for First Nations people and non-First Nations people to come together in the spirit of reconciliation and hope for generations of children to come.

Orange Shirt Day was created out of Phyllis’ story. In 1973, when Phyllis (Jack) Webstad was six years old, she was sent to the Mission School near Williams Lake, B.C. Her first memory of her first day at the Mission School was that of having her own clothes taken away – including a brand-new orange shirt given to her by her grandmother. In 2013, Phyllis attended the St. Joseph Mission (SJM) Residential School (1891-1981) Commemoration Project and Reunion events that took place in Williams Lake. At this event, Phyllis shared her story with those in attendance – and Orange Shirt Day was born.

Discussion

Bisschop followed her presentation with a class discussion of the meaning of reconciliation to the students, and how “we as individuals” can work towards reconciliation.

"The students at CCS were respectful, engaged and had great discussion questions," said Bisschop.

“Reconciliation means regaining friendships and moving forward,” said Latifah Severight, Grade 12.

The Grade 9 classes partook in a GSSD poster completion on "What does reconciliation mean to you?"

Grade 9 student Mataya Ball chose to do a water colour on her interpretation of reconciliation.

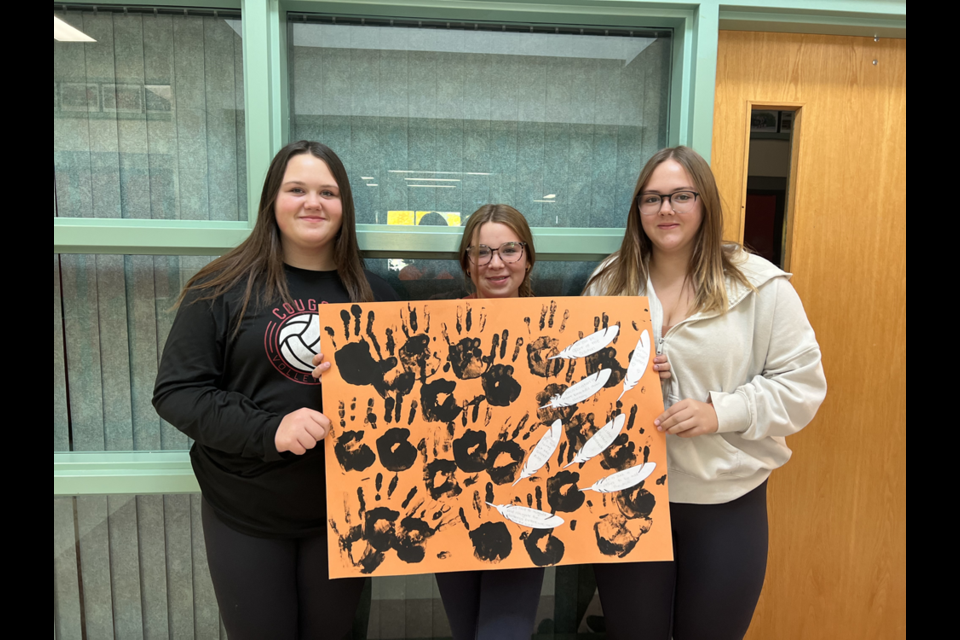

Grade 8 students Kaelyn Shukin, Heidi Parmley and Natalie Kosar entered their poster featuring quotes on truth and reconciliation, and included black handprints to signify every child matters.

Grade 6 students Mya Dutchak and Tobbi Effa coloured "Every Child Matters" pictures. Effa's was in English and Dutchak’s was in Dene.

Mykelti Johnstone, Maggie Lemaigre, Chance Weinbender, Mrs. Bisschop, Kenzee Kopelchuk and Aubree Wilson highlighted some of the detailed picture books available for Truth and Reconciliation.

“I believe reconciliation begins with education and was glad to be able to talk about Truth and Reconciliation with the students and show them some of the great books we have on that subject in our library," concluded Bisschop.