In a spring and summer dominated by anti-racism protests and public debates over controversial monuments, two antique dealers in Saskatchewan are quietly continuing to sell items that bear a symbol used for genocide, hatred and race-based politics.

A Regina antique store has Nazi Germany uniforms for sale, while a small-town Saskatchewan antique dealer recently sold a knife engraved with Nazi and SS logos.

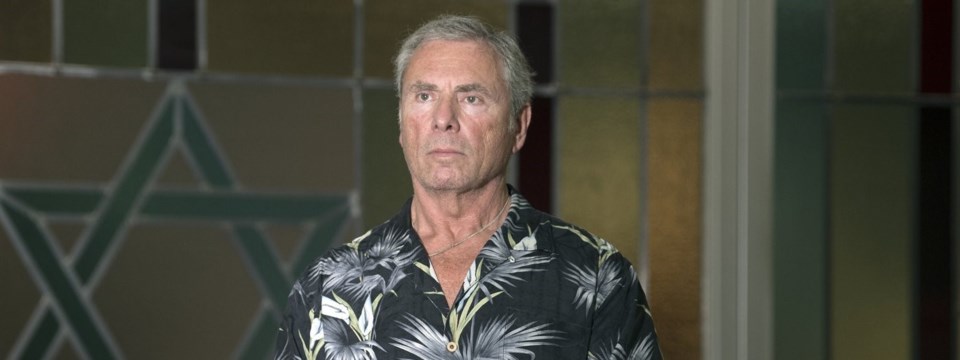

For Jeremy Parnes, the rabbi of Regina's Beth Jacob Synagogue, the sale of these items is complicated and troubling, leaving him with “mixed feelings."

“It's like anything else: I don't think it's black and white. I think there's a lot of grey. First of all, I think selling Nazi paraphernalia, promoting those things, is a good way or is another way that helps to promote anti-Semitism, and other forms of racial intent,” he says.

Krave Collectables in Regina has two Nazi Germany uniform jackets for sale: A grey, formal-looking one with the Third Reich eagles and swastikas on each side of the collar, and a black jacket with a red armband displaying a swastika.

On May 27, the Facebook page for Pippin’s Pickins in Chamberlain, 90 kilometres northwest of Regina, posted that it had sold a Nazi dagger to a private buyer. Photos of the dagger show a swastika on the handle and the German-language phrase Meine Ehre heißt Treue (my honour is loyalty) on the blade; the linked chain for the dagger’s holder is engraved with SS and skull-and-crossbones logos. Dale Pippin, the store’s owner, confirmed to the Leader-Post he sold the dagger.

Rabbi Parnes says despite the anti-Semitism he believes such sales promote, he doesn’t think they should be banned.

“If we were to somehow legislate it from out of the public eye, it won't stop. It will just go underground, and I think that's possibly more deleterious to the process,” he says.

“I'd rather encourage people to be better educated, to better understand (an object's history) and to make their decision accordingly.”

Pippin says his antique business derives from his passion for history, learning about it and selling historical objects, and from his 29 years’ worth of experience in retail.

“When I see a Nazi item, it's the same as seeing an item from the American Civil War. I don't look at it as an item of hate; I just look at it as an item with a lot more complicit history than some of the more pleasant items I sell,” he says.

He describes the SS dagger as a complicit item.

“I was looking at a dagger (that belonged) to a man who was absolutely hate and evil. This would have been one of Hitler's worst of the worst. A real nasty bastard. They would have had full knowledge of what was going on,” Pippin says of the knife’s likely original owner.

When he sold it, Pippin told the buyer of the knife’s history and its usage, as he says he does with other historical objects.

He says he tries to respect people’s "line of sight" with such items. “When something is that historically difficult, you don't display it. It's off to the side where it can be seen, but it's not offensive to the eye.”

Nazi Germany was responsible for the genocide of six million Jews in the Holocaust, as well as the killings of thousands more people, including those who were gay, of certain ethnicities or religions, and disabled. The SS oversaw the Nazi's extermination agenda and death camps.

Asked to consider the possibility that Saskatchewan’s Jewish community may have relatives affected by the Nazis, Pippin says, “we're all immigrants, we all came here at a different time ... We're all probably going to be scared or have a bad memory of something from another country that we come from, or when our family or when our friends or when our lineage was done wrong somehow.”

Krave Collectables owner Gary Hudy wouldn't agree to an interview unless he could proof-read the article before publication, a condition the Leader-Post declined.

In March 2014 he spoke with the Saskatoon StarPhoenix at a trade show, where he had Nazi items available for viewing upon request. Back then he told the newspaper he shows respect for Jews by keeping more emotional items under his display table, and that he explains the meanings behind the war items he shows. He thought debate about controversial items was good to serve as a reminder of the Nazi’s actions.

"I think it's a necessary issue to discuss. Any discussion is positive.”

University of Saskatchewan history professor Alessio Ponzio says German law mandates how vendors are allowed to sell such items.

“You can own Nazi memorabilia in your apartment. But you can't show them. You can buy the memorabilia, but the person who is selling the memorabilia must cover the swastika,” he says.

Italy is more open with its past history of fascism under Mussolini: “In Rome you can still walk around and see the fasces, the symbol of the regime, all over the city … We have a huge obelisk with the name of Mussolini in front of Juventus (Football Club) stadium in Rome,” he says. Market vendors can display and sell calendars and wines “with the face of Mussolini.”

There are no such laws restricting or regulating the sale of Nazi items in Canada.

Jewish advocacy group B’Nai Brith Canada encourages sellers like Pippin and Hudy to “sell or donate” their items to a museum for educational purposes, says Ran Ukashi, the group’s league of human rights director.

He allows that selling Nazi items is not necessarily an endorsement of Nazi policy. “However, for many Canadians, and not only Canadian Jews, the idea of selling such items for profit is distasteful and extreme.”

Rabbi Parnes has experience with that extremity.

About four years ago, the nephew of a Second World War veteran met him at Beth Jacob Synagogue.

As a member of the Canadian forces, his uncle had to clean up the Nazi death camps when the war ended. The uncle photographed piles of corpses and open graves of camp prisoners for documentary evidence. He left the photos to his nephew.

As the nephew began showing the pictures to people he knew “in small-town Saskatchewan,” he began receiving offers to sell the photos.

One man offered the nephew $5,000. Asked why, the potential buyer replied, “‘that's all we need is for those damn Jews to have another excuse' — or words to that effect,” Parnes explains.

The nephew then decided he had to be more proactive. He donated the photos to Parnes, who in turn gave them to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial centre in Jerusalem.

In his mind, Rabbi Parnes says, “There are three kinds of people in this world, sort of generalized: those who will be anti-Semitic, or hateful, anyway; those who aren't; and then those in the middle who clearly don't know which way to go.”

That’s why he thinks selling Nazi memorabilia presents an opportunity to educate people. “This is maybe not necessarily the way you want to live your life, behave, or treat other people," says Parnes, "any more than you'd want people to treat you.”