NORTH BATTLEFORD — Silence. It is a key hallmark of trauma. The inner thoughts can entrap one’s mind. A vicious cycle of repetition can induce one’s actions, behaviours, or emotions.

Yet, “Trauma will not beat us, because we are still standing today.”

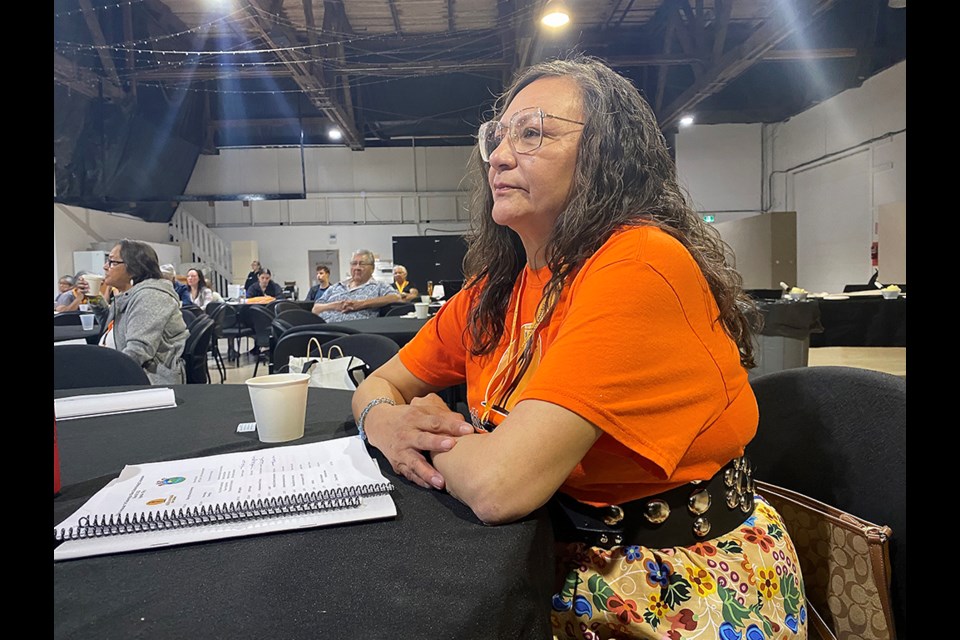

Those are the words of Dr. Sharon Acoose, who was among the dozens of speakers at the Acâhkos Awâsisak - Star Children: A Gathering to Share Cultural Healing.

The event was being held over two days at the Western Development Museum in North Battleford, gathering residential school survivors and those in the North Battleford community and beyond to share in the reconciliation process. Over 180 attendees were registered for the event, not including walk-ins.

The activities listed include sections of reconciliation, kinship, and traditional games/activities/dances.

To engage in the process of reconciliation is to explore the notion of intergenerational trauma further.

Intergenerational trauma is defined as a trauma that gets passed down from those who directly experience an incident to subsequent generations. Whether that trauma that is passed down is physical, emotional, or mental, can vary. It can be a process that as Dr. Acoose notes, can tear you from the inside out.

An example is the notion of lateral violence, where anger or rage is directed toward members within an oppressed community rather than towards the oppressors.

But how is intergenerational trauma dealt with?

Rather than trying to categorize or simplify the concept, the convention serves as both a starting and continual point of dialogue within the community. It is a place of shared experiences, a place to reflect, a place to forgive, a place to heal, but most importantly, a platform to use the human voice to both reclaim and maintain identity.

Multiple sources, whether young or old, alluded to the notion of an erased or subsided identity; yet through conventions and discussions like this, there is an opportunity to learn and in some cases, relearn.

For Karen Whitecalf, who was the project manager for the convention, the conference aims to kickstart cultural healing. Among the long-term goals for the group is the creation of a survivors group in the Battlefords.

“The older generation…they were children at one time …but what wasn’t taught [in the residential schools] was human emotion.”

Warrior Program Facilitator Quentin Weenie of the Kanaweymik Child & Family Services Inc. agrees. He alluded to how residential school experiences centre around the idea of chores, and how there was rampant emotional neglect, an aspect he sees his kids today being cycle breakers of. The ability to instinctually verbalize phrases such as “I love you, have a nice day,” to family are examples that are taken for granted today, that was not so in the past.

By continuing to share survivors’ stories, the hope is that the pattern of disruption not only ends, but others take a leap of faith in their healing and knowledge, to make sense of their own lives.

Whitecalf believes that the younger generation will benefit from this healing process, becoming stronger, smarter, and ultimately, not having to experience the intergenerational trauma that so many in attendance have.

The goal to end intergenerational trauma is realistic, however, conventions such as this remind everyone of the ability of humans to be interconnected.

Where does this leave the story of trauma then? According to Weenie and others, it remains a part of history, but the narrative changes.

“Our story doesn’t stop at the trauma. Our story becomes beautiful afterwards.”