Naming diseases is a complicated business.

To be useful, a name needs to be unique, descriptive, and memorable so it can be referenced easily, especially when medical situations become urgent. Though the easiest way to name illnesses may be just to give them identification numbers, that system becomes extraordinarily difficult to reference efficiently when time is of the essence.

It may seem intuitive to name diseases based on their origins or discovery locations; however, this approach also presents issues.

As our world increasingly boasts a global citizenry, illnesses—and their names—can be spread across various cultures, making it essential to be sensitive to and inclusive of all who may encounter them.

In light of recent conversations about disease nomenclature, Stacker investigated how "monkeypox" and other disease names have caused controversy, using a collection of news, scientific, and government sources.

While this is not an all-inclusive list of the issues surrounding the naming of diseases, it explores several fraught means by which illnesses are given nomenclature that becomes shorthand for public discussion.

Canva

Disease names tied to geographic locations

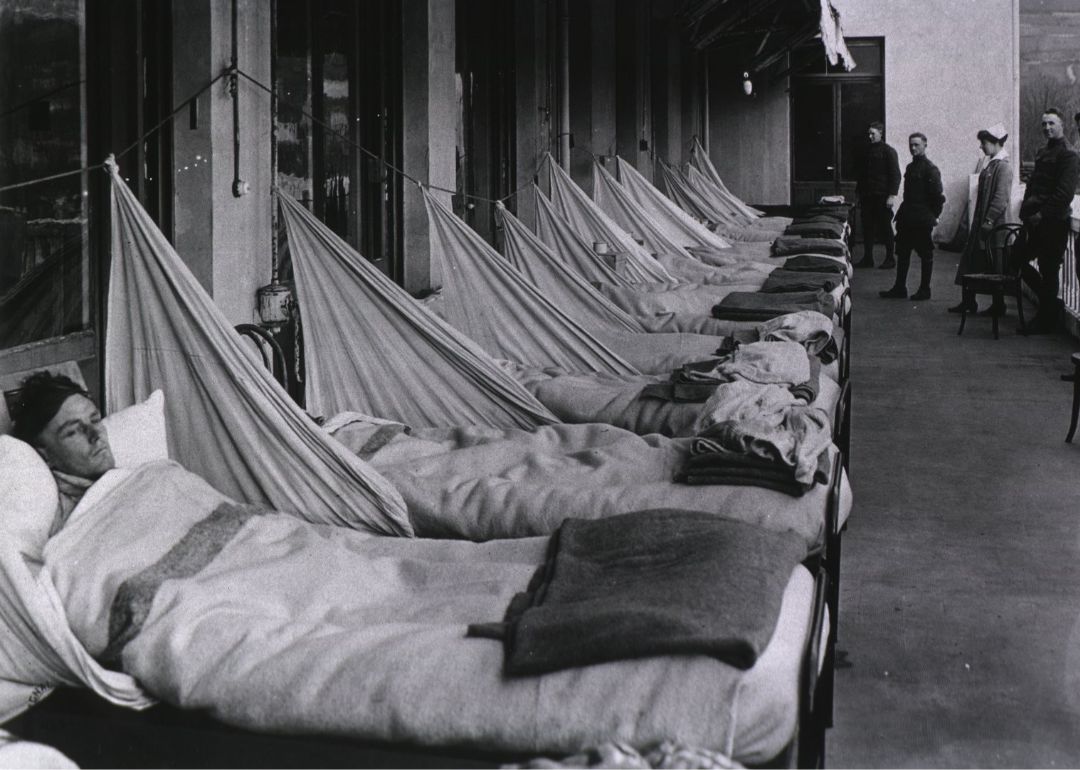

Naming illnesses based on where they were presumed to have originated was a common practice for decades. The "Spanish flu" from the early 1900s is just one of many toponymous diseases that earned its name based on a physical place.

However, in 2015, the World Health Organization released new guidelines that advised against this practice. When an illness becomes irrevocably tied to a place, people from that place often face discrimination or violence—even if the illness is later proven to have come from someplace different.

One recent example of a toponymous disease causing backlash occurred at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when some people, including then-President Donald Trump, referred to the novel coronavirus as the "Wuhan flu" or the "Chinese virus." Many experts and medical professionals spoke up, stating that the monikers were xenophobic and prompted anti-Asian hate.

Other diseases named after places include the Zika virus, named after the Zika Forest in Uganda; Marburg virus, named after Marburg, Germany, where more than 30 cases of the illness were recorded; and Middle East respiratory syndrome, named after being first found in Saudi Arabia.

Canva

Disease names connected to an animal species

The list of diseases named after animal species is long and includes monkeypox, swine flu, and mad cow disease, among others. Though it may seem harmless to name an illness using its presumed species of origin or a carrier species, WHO guidelines also warn against this practice.

In the wake of swine flu (also known as H1N1) outbreaks in other countries in 2009, Egypt ordered the slaughter of all pig livestock in the country despite not having any cases, resulting in the killing of about 300,000 animals.

Most recently, the name "monkeypox" has incited people to attack primates in zoos and their natural habitats out of fear of contracting the virus. WHO officials have attempted to redirect disease prevention efforts to focus on human-to-human transmission, but the prevalence of the "monkeypox" name isn't helping the cause.

In addition, 29 experts wrote an article in August 2022 calling for the term "monkeypox" to be changed due to its racist connotations against Black people and people of African descent.

Votava/brandstaetter images via Getty Images

Disease names that include the name of an individual person

It's not unusual for scientists to name their discoveries after themselves: Halley's Comet, Verreaux's sifaka, and Avogadro's number are just a few examples. But when it comes to physical illnesses, the politics of having an individual's name in the disease name becomes tricky.

One such disease the WHO specifically named in its updated naming guidance is Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, first described by neurologists Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt and Alfons Maria Jakob but named by a third neurologist, Walther Spielmeyer.

Names in this category are discouraged because they are not descriptive; however, the situation can be further complicated when the condition is named after a controversial figure. This is the case for Asperger's syndrome, which is no longer an official diagnosis by the American Psychiatric Association as of 2013.

Hans Asperger was a Nazi scientist during the Second World War and was responsible for the deaths of dozens of children; however, his dark story was not revealed publicly for many years after the diagnosis became common. The physical and mental conditions initially associated with Asperger's syndrome are now classified under the diagnosis of autism. However, laypeople still use the name despite its removal from official medical practices.

Canva

Disease names that refer to a group of people

At the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and before the virus had been studied in-depth, it was called "gay-related immunodeficiency" because of its prevalence among homosexual men.

At the time, it was assumed that sexual orientation had to be a causal agent of the disease. Though it is now known that HIV is not caused by sexual orientation but is transmitted by sexual contact or contact with infected blood, homophobia still lingers around the disease, serving as a warning for future disease names to mitigate discrimination caused by nomenclature.

Beyond HIV, controversy ensued during outbreaks of H1N1, or swine flu, in Israel. Because Israel has large Jewish and Muslim populations, many of its citizens took offense to the reference to pigs in the flu's name because pigs are neither kosher nor halal.

As a result, Israel's deputy health minister announced that the illness would instead be called "Mexican flu," based on the finding that the first human H1N1 patient was Mexican. This caused the Mexican ambassador to Israel to launch an official complaint against the Israeli government, ultimately resulting in Israel's acceptance of the term "swine flu" after all.