WESTERN PRODUCER — What takes a regular old thunderstorm and turns it into a severe thunderstorm, or occasionally, into a thunderstorm that you truly remember.

Typically for severe thunderstorms to develop we have a hot humid air mass in place at the surface and the air a few thousand meters up is very cold. This provides an environment where rising air will continue to rise, or we would say there is plenty of lift.

Damaging hail fell over patches of western and central Manitoba June 12, 2025 in a series of storms that also spawned several tornadoes. | Photo by Alexis Stockford Venting\

Add to this a strong jet stream overhead that will vent the accumulating air at the top of the storm, and we are ready for severe thunderstorms. Over the last few weeks or so, we have had plenty of cold air aloft, but we didn’t really have a lot of hot and humid air at the surface, but there was enough heat and humidity at the surface to generate rising air. Combine this with several occurrences of strong jet streams overhead and we ended up seeing some severe thunderstorms develop. The question then is, what can Mother Nature add to the mix to make things even worse?

The first and probably most important “extra” ingredient that can be added to the mix is to have the wind change direction with altitude. Remember that the atmosphere is three-dimensional; that is, air can flow horizontally, but this horizontal direction can change as you move upwards. Why would this have an impact on our storm?

To put it in a nutshell, this change of direction can cause the developing storm to rotate. Picture what would happen if you took a rising parcel of air and push on it from the south when it is at the surface. Then as it rises a couple of thousand feet the wind switches direction and now blows from the east. Then a few thousand feet further up it is blowing from the northwest. What would happen to our rising parcel of air? It would get twisted — it would start to rotate.

Spinning

If we can get air to rotate counterclockwise it will start to create an area of low pressure. Air flows, or spirals inwards, in a counterclockwise rotation. This means the air will be converging or bunching up near the center of this rotation. This converging air can either move downwards or upwards. Since the ground is in the way for the air to move downwards, plus the air is unstable which means it already wants to move upwards, this results in upwards moving air — often forced to move upwards very fast. So, if we can get our severe storm rotating, a small-scale area of low pressure can form and that helps the air to rise even more than it would without the rotation. When this occurs, it is referred to as a super cell thunderstorm, or a mesocyclone.

The second thing a rotating thunderstorm can do is to nicely separate the area of updrafts and downdrafts. This is important, since the downdrafts, even with a severe thunderstorm, will eventually cut the updraft off from its source of warm moist air. Once this happens the storm quickly weakens.

In a rotating thunderstorm, the source of warm moist air is maintained, giving these storms a long life and a lot of moisture to produce heavy rain. This is something parts of the Prairies would like to see sooner than later.

Tornadoes

Another aspect of the storm a rotating column of air can provide is the conditions for tornadoes to form. While we still do not fully understand how tornadoes are formed, we do know that rotating thunderstorms can and often do produce tornadoes.

It is believed that rotating columns of air can get squeezed into a narrower shape. As this happens, the wind speeds increase, eventually producing the tornado. It’s the whole theory of the conservation of angular momentum. Take a large thing that is spinning slowly like a big wide column of air and shrink it down, the objects rotational speed needs to increase and visa-versa.

The classic example of this is the spinning figure skater pulling in their arms to increase their rate of rotation, but more on this when we take a closer look at tornadoes.

Like most things in nature, thunderstorms rarely behave like a textbook example. Even when all the ingredients are there, sometimes no storms will form, or sometimes some key ingredient is missing yet we get a really severe storm — this is what makes weather so interesting.

Missing

As we know, not every thunderstorm that develops becomes severe, in fact, much of our summer rainfall comes from garden-variety thunderstorms. These can be air mass thunderstorms, which, as the name indicates, develop in the middle of a typical warm summer air mass. Because they are in the middle of an air mass, a number of the key ingredients for severe storms are missing.

As I mentioned earlier, usually in the middle of an air mass, the temperature will not decrease that rapidly with height. The wind will usually remain constant with height, and there will probably not be a jet stream overhead. Nonetheless, we can still have enough heat and humidity for the air to rise, and thunderstorms will form.

Since these storms don’t rotate or have any way to vent the rising air from the top of the storm, they rarely last long. The accumulating air at the top of the storm will eventually fall back down as a downdraft, wiping out the updraft and essentially killing the storm. The whole process from the start of the storm to the downdraft killing it can be anywhere from 30 minutes to an hour or two.

While these storms are short lived, they can give brief periods of heavy rain and the odd, good gust of wind, especially when the downdraft first hits the ground.

The same thing can occur with frontal storms, where all but one or two of the main ingredients could be in place, thunderstorms will form, but they just can’t pull everything together to go from just garden variety storm to a severe storm.

These storms often provide us with just the right amount of precipitation just when we needed it during the summer.

In the next issue we will start to examine all the different types of severe weather that can accompany severe thunderstorms.

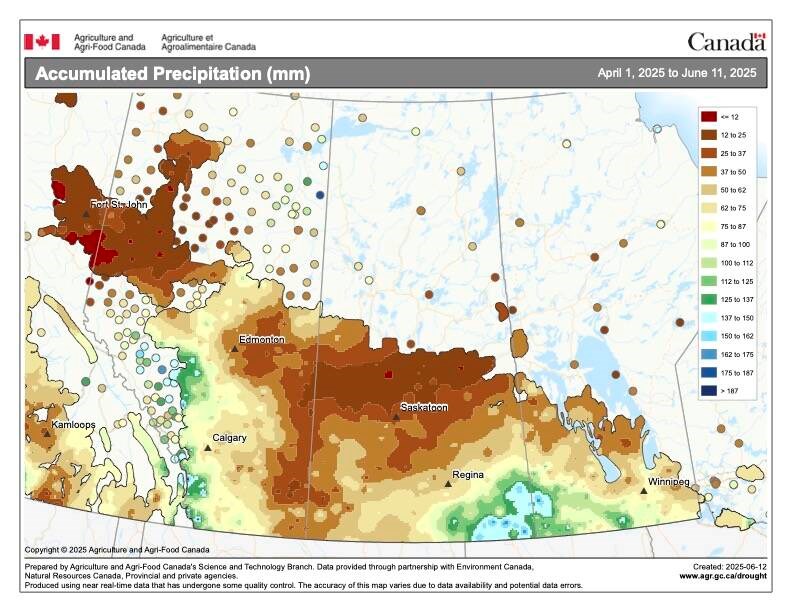

This week’s map shows the total amount of precipitation that has fallen across the Prairies so far this growing season (April 1 to June 11). Looking at the map you can see that the only areas that have seen significant rainfall are over far western Alberta, along with southeastern Saskatchewan and western Manitoba. It has been a very dry start to the growing season across far northwestern Alberta along with much of central Saskatchewan.

About the author

Co-operator contributor

Daniel Bezte is a teacher by profession with a BA (Hon.) in geography, specializing in climatology, from the U of W. He operates a computerized weather station near Birds Hill Park.

Related Coverage

What causes heavy rainfall on the Prairies?

The four theories of tornado formation

Blizzards are inescapable but their costs aren’t always

Severe summer weather: tornadoes

Back to our look at severe summer weather

Thunderstorms and heavy rainfall