WESTERN PRODUCER — In February, Agriculture Canada announced $182.7 million in funding to help farmers fight climate change.

The money will be distributed to farm groups and non-government organizations that will use the funds to promote the use of cover crops, rotational grazing and improved nitrogen management.

The funding has two main objectives:

- To pull more carbon out of the atmosphere and store it in the soil.

- To reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture.

“The fight against climate change is not only about reducing Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions, but also helping farmers to innovate and adopt more sustainable farming practices,” said agriculture minister Marie-Claude Bibeau in a news release.

Cover crops, the practice of seeding plants that cover the soil but may not be harvested, is a key part of this $182 million project. They can help store more carbon in the soil but they may not reduce nitrous oxide emissions on the Prairies, says an Agriculture Canada scientist in Lethbridge.

“The soil is the farmer’s biggest resource…. Anything you can do to make your soil healthier and better is probably a good thing. Cover crops, I think, will add to that,” said Roland Krobel, who specializes in climate change and GHG emissions from farming.

“(But) the semi-arid Prairies are not well set up for cover crops.”

Krobel, in a phone interview from his home in southern Alberta, defined a cover crop as a secondary crop that is grown after the main crop.

In Western Canada, such cover crops would normally be seeded in September and continue growing until freeze up.

“What the plant will ideally do, it will definitely do photosynthesis. It will draw CO2 out of the atmosphere and store it in the biomass,” he said. “You increase the overall biomass production of your field, on an annual scale. Some of that carbon will stay behind and therefore add higher input into the soil.”

The amount of carbon added to the soil depends on soil moisture and fall weather, but it’s reasonable to say that a cover crop will store more carbon in the soil than a bare field.

“It will still do better… than if you don’t grow anything,” Krobel said.

“If it grows somewhat, it will still protect your soil and keep it in place.”

So, keeping the ground covered for more months of the year will store more carbon in the soil. But the impact on greenhouse gas emissions is more complex, Krobel said.

“They may not necessarily benefit, with respect to nitrous oxide emission,” he said.

“We don’t necessarily increase or decrease nitrous oxide (with cover crops).”

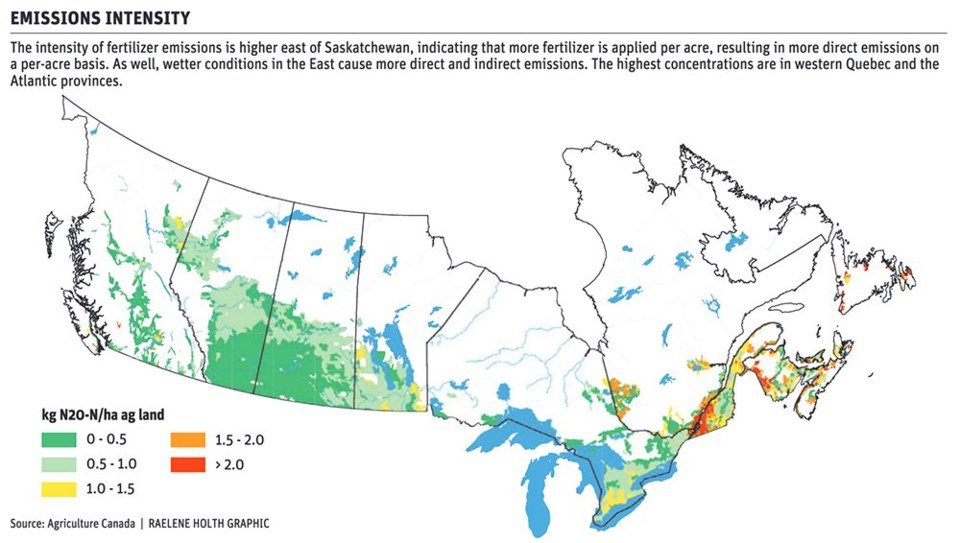

On grain farms the main source of emissions is nitrous oxide, a powerful greenhouse gas connected to nitrogen fertilizer and manure. One kilogram of nitrous oxide released into the atmosphere is equal to 300 kg of carbon dioxide.

“The application of nitrogen fertilizers accounts for the majority of N2O emissions,” said the Environmental Protection Agency in the United States. “Emissions can be reduced by reducing nitrogen-based fertilizer applications and applying these fertilizers more efficiently.”

In theory, a cover crop could work like a catch crop, where the plants take up nitrogen from the soil and hold the nutrient, preventing it from being released throughout the winter and into the spring.

“The intent is basically to take the leftover nitrogen… that your main crop didn’t use…. So, it’s stuck (in the plant) and doesn’t move around,” Krobel said. “If you do use a catch crop and make optimum use, it could possibly reduce nitrous oxide emissions.”

But that approach is more feasible in southern Ontario, where soils may not freeze solid in the winter.

In Eastern Canada, when soils are covered with snow, microbes in the soil remain active and the “microbial engine that creates nitrous oxide keeps going,” Krobel said.

That nitrous oxide gets trapped under the snow. When temperatures rise during winter and the snow melts, the nitrous oxide is released.

Holding more nitrogen in a cover crop could reduce the release of nitrous oxide.

The Prairies, however, are different. Soils in much of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and parts of Alberta are frozen from December to March. Most of the nitrous oxide is released in spring when soils warm.

A cover crop may not reduce the burst of N2O in the springtime.

“If your crop gets winter killed, it will decompose,” Krobel said. “When it warms up, all this nitrogen becomes available. You fertilize for your main crop (and) it all comes together. You could actually get a bigger spike (of nitrous oxide emissions in the spring).”

Other factors will influence what a cover crop can or can’t accomplish around climate change.

A lot depends on the type of cover crop. If a farmer seeds legumes in autumn, those plants will fix nitrogen and add nutrients to the soil. But a non-legume will use nitrogen.

Another question is the purpose of the cover crop. Will cattle graze on the cover crop in December or not?

Scientists haven’t done enough field research to understand how cover crops will influence nitrous oxide emissions in Western Canada.

“It’s a complicated topic,” Krobel said. “We don’t have really a good scientific (grasp), in terms of measurement understanding… of what’s going to happen.”

What’s more obvious is that a cover crop will increase the amount of carbon stored in the soil. If millions of acres of clover, radishes and other plants are seeded in the fall, across the Prairies, western Canadian farmers will remove more carbon from the atmosphere.

But, how much?

When calculating the contribution of cover crops, scientists need to know the number of acres and the amount of vegetative growth before freeze-up.

On the Prairies, a lot depends on soil moisture.

In a warmer and wetter climate like southern Ontario, farmers could probably grow a fall cover crop every year, Krobel said.

In Western Canada, especially dry regions like southern Saskatchewan, every year isn’t realistic.

“(Some) years you may want to stay away from it,” he said. “For the Canadian Prairies, we probably have to assume the cover crop only goes in every second or third year.”

However, since the Prairies are huge, if one third of farmland was covered with growing plants in the fall, it could store a fair amount of carbon in the soil.

Plus, the cover crops should improve soil health and will provide high quality feed for livestock.

“It’s worthwhile to promote it,” Krobel said. “Whether the cover crops, by themselves, are going to save climate change for us? Probably not…. It may become viable in the future. But it’s always going to be a moisture question.”