WESTERN PRODUCER — Much of western Saskatchewan and other parts of the province are at high risk of crop damage caused by herbicide carryover from 2021.

So, growers need to make “conservative” decisions when making cropping choices for 2022, says the provincial weed specialist.

If in doubt, producers should seed a crop that is more resilient to the herbicide molecules lingering in the soil.

“Most of the province is going to have a pretty high risk of carryover,” said Clark Brenzil, weed control specialist with the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture.

You want to pick the most tolerant crop, within the registered set of cropping options that are on the label…. Within those registered cropping options, there are going be a range of sensitivities.”

The problem is broader than Saskatchewan. Herbicides applied last year could also damage crops in Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

“In the 2021 growing season, many parts of Alberta and Western Canada experienced rainfall well below average, leaving many fields at risk of herbicide carryover,” Jeremy Boychyn, an agronomy research extension specialist with the Alberta Wheat and Barley Commissions, said in a post on the organization’s website.

Brenzil, who spoke at the Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation soil and crop management seminar, held Feb. 2, explained how herbicides degrade in the soil and how leftover herbicides could damage crops in 2022.

Many fields in Saskatchewan will have more herbicide in the soil because the chemicals degrade more slowly when soils are dry. When soils are wet and warm, the microbes in the soil are more active and herbicides break down at a quicker rate.

“That (microbial activity) is the most common pathway (for degradation), for most herbicides,” Brenzil said.

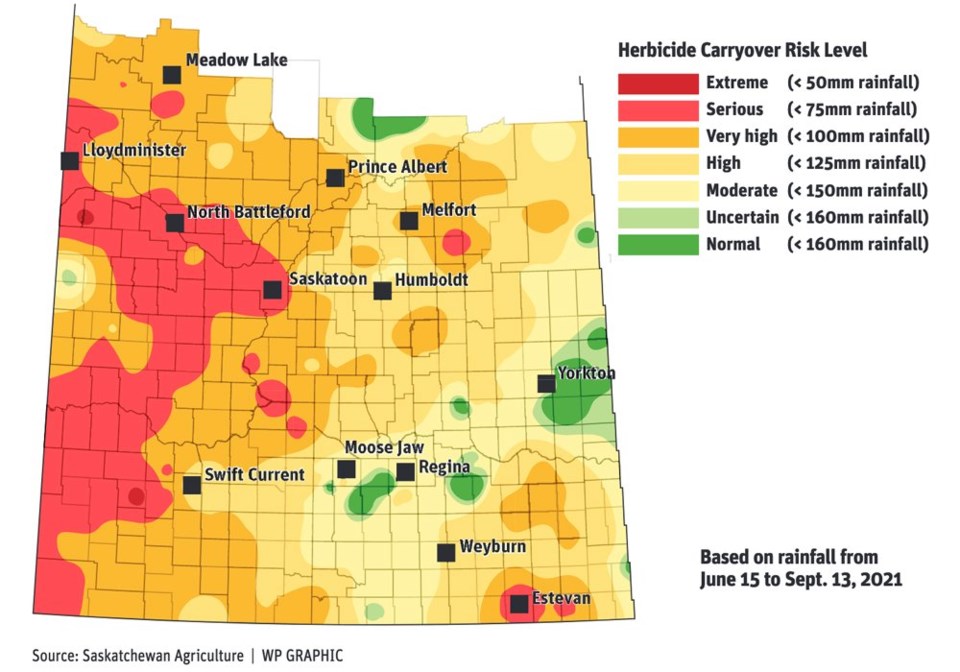

Most herbicides degrade from June 1 to the end of August, so Saskatchewan Agriculture produces a herbicide carryover map based on rainfall during that period.

Text accompanying the map states that rainfall following the application of a residual herbicide is the most important factor in the breakdown of herbicides.

The timing of rainfall is important.

Parts of eastern Saskatchewan received rain June 9. If a producer applied a residual herbicide before June 9 the product likely degraded quickly.

But if they waited to the middle of the month to apply the residual herbicide, more product is likely still in the soil.

“We can probably expect the moisture from a significant rainfall to last (as far as the breakdown of herbicides is concerned) for about a week,” Brenzil said in an email. “(They) are going to be broken down very close to the soil surface. So, moisture is likely to disappear relatively quickly from that area, if we have strong drying conditions.”

Saskatchewan Agriculture also has a herbicide carryover map for the period from June 15 to Sept. 13 to account for growers who applied product after the middle of June.

The maps, though, are estimates of rainfall in a region. An individual producer, say in Kindersley, may have less herbicide carryover than a farmer 50 kilometres away in Kerrobert, Sask.

“A producer’s own rainfall records are the most relevant to their own situation,” Brenzil said. “The producer’s own records are going to be the best predictor of risk.”

Another factor to consider is soil type.

Some herbicide molecules will bind to soils with more clay and more organic matter. When that happens, fewer chemicals are in the spaces between soil particles. Plant roots from a crop planted in 2022 will absorb fewer herbicide molecules from the soil.

Some parts of the Prairies received 50-75 millimetres of rain in late August, but growers shouldn’t rely on that moisture to break down herbicides.

“That will help, a little bit, but we know less about that (September) time frame,” Brenzil said.

Some producers may be considering a chemical analysis to gauge the amount of herbicide in the soil in a particular field but such testing isn’t a great option, Brenzil said.

“We’ve got good technology that can say: yes, this is how much stuff is in your soil,” he said, noting a portion of the herbicide could be bound to the clay and organic matter in the soil.

“You get a nice piece of paper that says how much is in your soil, but no one can really tell you with any certainty what that number means… (or) what’s going to happen.”

The drought and high risk of carryover prompted BASF to issue a notice to western Canadian growers.

In September, BASF urged growers not to grow certain crops in 2022 if they applied Solo, Viper or Odyssey herbicides in 2021.

“We all know that certain environmental conditions can delay the breakdown of herbicide residues in soil. But this year is different,” BASF said in its notice.

The BASF recommendations are for canola, durum and canaryseed. They can be found at agro.basf.ca.

Growers who are uncertain about carryover and have questions on specific products should contact the manufacturer, Brenzil said.

Company representatives can provide guidance on which crops are most tolerant of a residual herbicide and which crops are the most sensitive.

Sask Canola, Sask Wheat and Sask Pulse have also published a herbicide carryover factsheet. It can be found at saskcanola.com.