Stewards of agricultural lands have long recognized that the subject of water drainage is best never to surface if friendships are to be maintained.

In reality, drainage projects are not always controversial or met with dis-agreement, but a multitude garner that response. Water drained off one piece of land quickly becomes the problem of others located along the drainage network. Drainage projects in this area of the province require heightened scrutiny because of the potential for accumulated water from the whole Assiniboine Water-shed Stewardship Association (AWSA) area to move downstream into Manitoba.

On September 1, Herb Cox, minister for the province’s Water Security Agency (WSA) announced the new regulations for drain-age while at the same time announcing that the implementation would be initiated through pilot projects in the Spirit Creek drainage system and a second in the Souris Basin, near Stoughton. The pilot projects are to commence a 10-year effort to bring into compliance all drainage projects across the province.

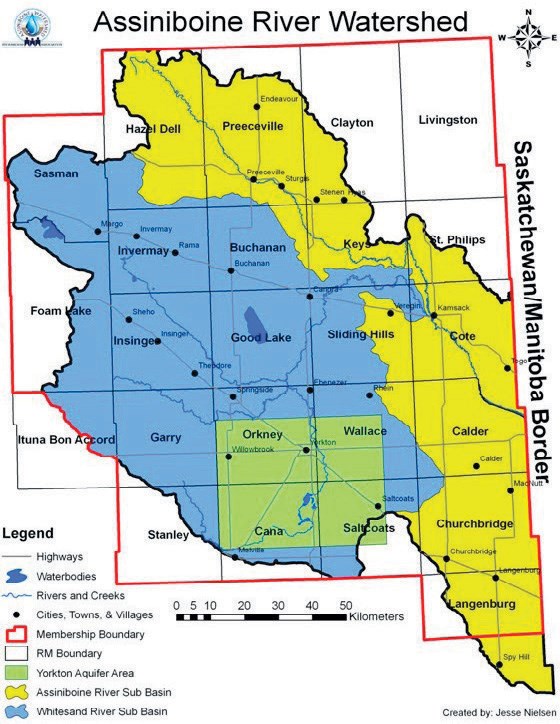

Don Olson of Sturgis, the AWSA chairman, noted that the local pilot project was not identified correctly in many provincial press releases. The Upper Spirit Creek Basin near Good Spirit Lake was often identified as the Assiniboine basin near Canora. Upper Spirit Creek actually refers to the drainage system located in the rural municipalities of Buchanan, Invermay and to a lesser degree in the RM of Hazel Dell. The system drains into the north end of Good Spirit Lake.

It is necessary to point out that the implementation of the new regulations is the responsibility of the WSA, where AWSA’s main responsibility is source water protection, said Olson. The two agencies do work together but responsibilities differ.

The new regulations announced by WSA are the first changes made in Saskatchewan in 35 years, according to a WSA release. These regulations are part of the development of a risk-based agricultural water management strategy that will improve the overall process, including applications and investigating complaints, and will help prevent future issues, stated the WSA release. The new regulations are to ensure impacts related to flooding, water quality problems and habitat loss are addressed as part of the drainage works approval process.

Prior to these regulations being adopted, all drainage works constructed before 1981 were exempt from the process involved requiring approval for drainage projects.

The new regulations are being phased in over the 10-year period, but this area will be among the first to recognize a change in the permitting system, Olson said. AWSA was selected because it has been a leader among the 11 watershed areas certified in the province. Planning for the creation of AWSA began in 2004 and when it was officially formed in 2007, it was only the fourth stewardship area certified in the province.

Though the new regulations focus more on future projects requiring WSA permits, the regulations address all drainage projects, even those grandfathered in the 1981 regulation review, he said.

There are so many drain-age projects in the area, it is difficult to even estimate the number, Olson said. Though it was always necessary for drainage projects to be licensed, there are count-less “illegal” projects. Most are not much more than simple ditches carved into a farmer’s field. With the equipment now available to farmers, such ditches are easy to construct and many are done without being ob-served by neighbours.

Because the AWSA system is located in a high-risk area of the province (drained water ends up in Manitoba), all drainage projects will be scrutinized, he said. Though he can not be certain, Olson suspects that the older drainage projects, especially those established before 1981, will not be the target of scrutiny early into the 10-year mandate leading to the permitting of all structures in the province. It is conceivable that when the WSA identifies existing drainage structures that will not be approved, landowners may be ordered to close those drainage channels.

The WSA states that the risk-based agricultural water management strategy made possible by the new regulations will improve the overall process, including applications and how complaints are investigated complaints, and will help prevent future issues. Cox said the new regulations are expected to ensure impacts related to flooding, water quality problems and habitat loss are addressed as part of the drainage works approval process.

Where the WSA approves projects, those constructing the drainage projects will be required to use best practices in design and construction of works to reduce impacts of drainage on flooding, water quality and habitat. Works deemed “moderate risk” will be subject to further conditions, while “high risk” and “extreme risk” activities may be required to take addition-al steps to offset expected impacts and, in some circumstances, approvals may be denied, states the WSA release.

A big difference in how drainage infrastructure will be handled, the WSA re-lease states that approval holders may be required to install and operate structures to control release of water or may be required to retain some surface water or storage space for water. The new regulations will allow written landowner agreements to be used as evidence of land control. Legal easements on land titles will still be needed for “high investment” projects such as multi-party, organized or publicly funded works.

Patrick Boyle, a spokes-person for the WSA, said the new regulatory approach is based on the concept of “responsible agricultural water management.” Any-one planning a farm drain has the responsibility to “design, construct and operate the project properly and undertake necessary actions to minimize the negative impacts of drainage to an acceptable level.”

The next phase of the this agricultural water management strategy will be the development and refining of policies and program delivery which will be developed in the pilot projects, he said.

Local producers, water-shed authorities and representatives in the pilot project areas have committed to working with the WSA to implement the new water management strategy and help bring existing drainage projects into compliance, Boyle said.

In announcing the new regulations and the pilot projects, Cox said the watershed authorities representing these areas have worked well with the establishment of the WSA (a combination of several departments within the Ministry of Environment). In reaction to recent flooding events, it was a logical step to start implementing the regulations while working with these watershed stewardship associations.

Cox said the new regulations were created after extensive consultations with about 500 public participants and 15 industry and environmental groups, which provided input into the creation of the new approach to drainage in Saskatchewan.

In a press release from the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities, Ray Orb, SARM president, said that organization welcomes the regulations which will address deficiencies identified in the previous system.

The WSA has chosen the new approach to drain-age management as part of its 25-year water security plan, said Boyle. Many of the problems associated with local and large-scale downstream flooding, degraded water quality and negative impacts on wet-lands and shorelines, can be avoided with carefully planned drainage and appropriate steps to reduce impacts, said Boyle. Central to the new approach is the concept of responsible agricultural water management, where the drainage proponent takes responsibility to design, construct and operate the project properly and undertake necessary actions to minimize the negative impacts of drainage to an acceptable level.

Drainage complaints response will be focused on regulatory compliance rather than technical investigation, he said. For the pilot projects, Boyle said work will include working with the local watershed group to implement the new drainage approval process for both new and existing works and promoting available incentive programs, including Farm Stewardship Program funding for flow control and erosion structures and wetland retention and restoration