Part One in this series described the audacity of a group of volunteers ready to take on the daunting task of organizing the first film festival to be held in North America. Part Two picks up the story with the second Yorkton International Film Festival in 1952.

From 1952 until 1956, the audience voted on the winning films in each film category at the festival. The ballot slips with their comments were passed on to the filmmakers as a form of adjudication. Certificates - very nice certificates Secretary Nettie Kryski said - were issued to the top three rankings. They were truly People's Choice awards. These folks knew what they liked and for the most part, they liked what they saw.

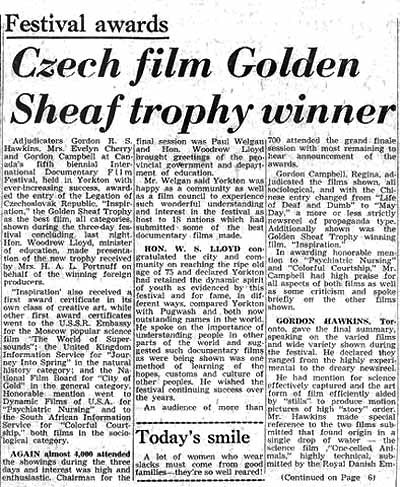

The format changed in 1956. Film experts judged the films and selected those to receive the winning certificates. The Yorkton International Film Festival had moved from a People's Choice format to one adjudicated by professionals for professionals. The change had to happen if the festival was to attract film entries of the highest quality. That same year, adjudicator Frank Morriss of the Winnipeg Free Press proposed an award for the best film of the festival. He suggested a golden sheaf as the design motif, a design that has become today the festival icon.

Unafraid of change, the Yorkton Film Council had the foresight and audacity to adapt to challenge the conventions of the day. One convention was a deep-seated fear of all things communist.

The 1950s was the era of the Red Menace. The American House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) blackballed anyone they considered communist or sympathetic to communist ideals. As a result, actors and other film industry people found themselves out of work. Charlie Chaplin, a British citizen, was denied an entry visa to the United States. And if you think that Canada rejected such nonsense, think again. The Canadian government instituted PROFUNC, a program where prominent functionaries within the Communist Party and their supposed sympathizers could be arrested and imprisoned without warrant in a state of emergency. Roland Penner, former Attorney-General of Manitoba, was "on the list". It is suspected that Tommy Douglas, Premier of Saskatchewan, was there as well.

Into these prevailing attitudes stepped the folks of the Yorkton Film Council. In 1955, the council showed a film called The Salt of the Earth. The film, more documentary than not, was about a courageous group of Mexican miners who had gone on strike to protest a difference in safety regulation and enforcement between themselves and their Caucasian counterparts. The film was banned in the United States even though it had received strong reviews from the New York Times. The problem was that the funding for the film came in part from a union where some of the leaders had ties to the Communist Party. Some of the actors and the director had been blackballed by HUAC. December 11, 1955 the Yorkton Film Council screened the film at Castle Hall. Perhaps they didn't know about the film's reputation. Perhaps they did. It is reasonable to assume they did given what happened one year later.

In 1956, two officials from the Embassy of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics arrived in town to view proceedings at the film festival. Two years later, the Yorkton Film Council learned that Moscow wanted to mount a similar venture and the two officials had come to Yorkton to learn about festival organization. However, the presence of the two Soviets in Yorkton raised suspicions and two Mounties were sent to tail the two men through the streets of the city and to happenings at the film festival - the Rotary Club luncheon and the closing banquet at St. Gerard's Parish Hall, two events where espionage was hardly likely. Needless to say, the investigation became the talk of the town. And then, someone - and who knows who - spirited the Soviet delegation down the back stairs of the Balmoral Hotel where they were staying. The RCMP members were left to cool their heels in the hotel lobby. Clearly, the citizens of Yorkton saw the Red Menace as less than menacing.

That same year, the council accepted films from the People's Republic of China. The Venice Film Festival fifteen years later made the unsubstantiated claim that its competition was the first to receive such entries. Not so, Venice. Yorkton was ready to defy the conventions of the day that saw espionage and infiltration behind every contact with Communist countries.

Such action was called audacity and audacity was the continuing hallmark of the Yorkton International Film Festival.