YORKTON - Saskatchewan is today largely populated by people who can trace their roots to somewhere far from here.

With each family’s immigration to this place, there is a story to be told.

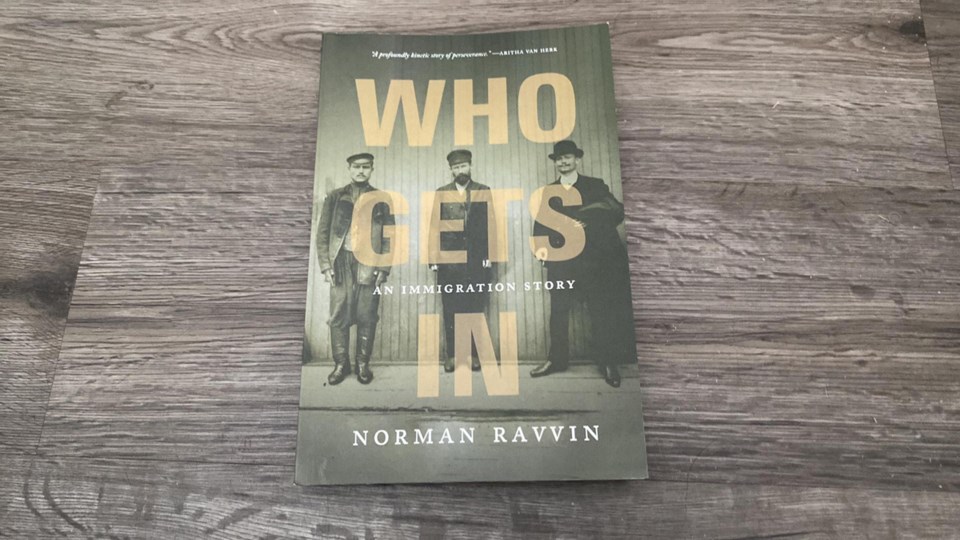

Norman Ravvin tells one of those stories in his recently released book; Who Gets In: An Immigration Story.

“Born from years of archival research, Who Gets In is author Norman Ravvin’s deeply personal family memoir, telling the story of his grandfather’s resolute struggle against xenophobic and anti-Semitic government policies. Ravvin also provides a shocking exposé of the true character of nation-building in Canada and directly challenges its reputation as a benevolent, tolerant, and multicultural country,” details the University of Regina Press page dedicated to the book at uofrpress.ca

The story traces the route of the author’s grandfather, Yehuda Yoseph Eisenstein, from Poland, across Canada to Vancouver, then back across the Prairies to Dysart (about 150 kms southwest of Yorkton), then Hirsch, in southern Saskatchewan, in the early 1930s.

Hirsch is a hamlet in the RM of Coalfields in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan and is located about 18 miles east of the city of Estevan along Highway 18.

According to Wikipedia, “Hirsch was founded in May 1892 by Jewish settlers as part of the activities of the Baron Maurice de Hirsch Foundation and the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA). It was the first settlement of the JCA and was named after the founder of the foundation, one of the most important Jewish philanthropists of the 19th century.”

“It was into this . . . my grandfather headed in 1931 as he went toward the job awaiting him in Dysart, roughly thirty kilometres northwest of old Fort Qu'Appelle and about 100 kilometres northeast of Regina. There he joined a phenomenon about which he would have heard talk in Vancouver: the settlement of Jews on farming colonies as well as the movement by Jews to small towns to become retailers, entrepreneurs of all kinds, cattle traders, the prairie version of the kind of middlemen that my grandfather had fashioned himself to be in Poland as he bought wheat from farmers in order to deliver it to mill owners. Some of these Western Canadian Jews lived in small communities or colonies that were wholly Jewish – as was the case at Hirsch and Lipton and at Edenbridge in central Saskatchewan,” writes Ravvin.

“In late 1933, my grandfather would find his way to Hirsch – among the earliest of the Jewish prairie colonies – but first he paid his dues at Dysart. Jews had settled there, among the Doukhobers, Swedes, and Ukrainian farmers, and had built up a makeshift communal network linked to nearby Markinch, Cupar, and Lipton. Jewish Dysart has entirely vanished, whether on the ground or in archival sources. Nothing seems to remain, though whenever I think that this is the case about some aspect of my grandfather's story, if I take things slowly, and abide by a kind of hit-and-miss process of research, something emerges.”

In 1930, a young Jewish man, Yehuda Yosef Eisenstein, arrived in Canada from Poland to escape persecution and the rise of Nazism in the hopes of starting a new life for himself and his family. Like countless others who made this journey from “non-preferred” countries, Eisenstein was only granted entry because he claimed to be single, starting his new life with a lie. He trusted that his wife and children would be able to follow after he had gained legal entry and found work. For years, he was given two choices: remain in North America alone, or return home to Poland to be with his family, explains the publisher page.

“It's the start of a vaudeville routine: a man is on his way across an endless country on a train. He can communicate only with people from his own part of the world, and often they are unfindable. Many others speak only one language: the King's English, as yet unknown. Although Canada liked to blow its own horn abroad – big gay posters and fat glossy pamphlets of yam-wielding farmers – there was no tutorial or gratis language instruction for the newcomers from Continental Europe in 1931 ... writes Ravvin in the book.

“ ... The traveller left a troubled continent but found his way into the midst of Saskatchewan's troubles, which preceded the 1930s. The first of a number of drought years occurred in 1929. The area of the province where my grandfather settled was not spared. Drought brought dust storms so dark that one had to light a kerosene lamp in the daytime. Farmers who'd known good years saw the price of grain plummet.”

“I do a lot of my work based on family stories,” said Ravvin, adding the story of his grandfather which was the basis of the book was “one (story) I had not properly pursued ... “It may be the last family story to tell.”

When Ravvin did turn his attention to what would become ‘Who Gets In’ he said he quickly came to realize it would be “a research heavy project.”

In the end it would be a near eight-year journey.

“I think I gave it the time and effort it required,” said Ravvin.

It was also a protracted project with the National Archive being closed to crucial research as part of the COVID lock-down.

Ravvin said he needed that access “for a final look at some material I wanted to consider,” he said.

The search through archival material at times was frustrating, hours of looking with little to show for it, admitted Ravvin, but because he was focused and knew what he sought “it had an element of detective to it, and it was challenging.”

Given the years that have passed since his grandfather arrived Ravvin said he was also constantly surprised by what he could unearth.

“What is remarkable is what was kept,” he said.

“Examining documents from various archives, Ravvin provides a heavily detailed account of his grandfather’s struggle to bring his family to Canada. Who Gets In is an important read because Eisenstein’s issue resonates so closely with Canada’s immigration policies today,” notes the publisher website.

Of course not everything was filed away.

“There were some really key questions I was not able to solve,” said Ravvin.

By the nature of the work there were questions he would have liked to have answered, but documentation was not found, and he would not assume to know what his grandfather may have thought decades ago.

So while racism is part of the story Ravvin could not know exactly what his grandfather dealt with, or felt about each situation.

Still as the publisher synopsis notes “by reproducing many of the letters between Eisenstein and federal officials, Ravvin allows readers to ponder how much of the officials’ reluctance to admit Eisenstein’s family was the result of their strict adherence to the law and how much may have resulted from discrimination because Eisenstein was Jewish. Government authorities, as Ravvin points out, had the power to crush individuals.”