Being something of a sci-fi nerd, author Harlan Ellison has long been well-known to me.

Ellison is an American writer whose principal genre is speculative fiction.

“His published works include over 1,700 short stories, novellas, screenplays, comic book scripts, teleplays, essays, and a wide range of criticism covering literature, film, television, and print media. He was editor and anthologist for two science fiction anthologies, Dangerous Visions (1967) and Again, Dangerous Visions (1972). Ellison has won numerous awards including multiple Hugos, Nebulas and Edgars,” details Wikipedia.

I also happen to like pulp tales, as previous review readers will know.

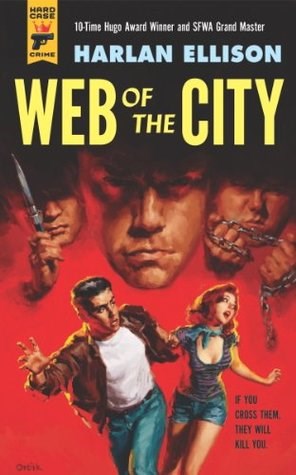

So when Web of the City came my way to review from Hard Case Crime, a label focused on pulpy tales I was surprised to find it was by Ellison.

In fact the book was a landmark for Ellison as a writer.

“It was my first book, written under mostly awful personal circumstances, and I’m rather fond of it. I’ve re-read it this last week, just to find out how amateurish and inept it is, and I find it still hold the interest. I even gave it to a couple of nasty types who profess to being my friends when they aren’t sticking it in my back, and even they say it’s worth preserving,” he writes in the books intro.

“So the book is alive once more.

The time about which it speaks is gone – the early Fifties; and the place it talks about has changed somewhat – Brooklyn, the slums. But it has a kind of innocent verve about it that commends it to your attention.”

To get the flavour there is a small teaser from the front of the book; “Rusty felt the sweat that had come to live on his spine trickle down like a small bug. He had made his peace with them, and he was free of the gang. That was it. He had it knocked now. He’d built a big sin, but it was a broken bit now. The gang was there, and he was here.

“The streets were silent. How strange for this early in the evening. As though the being that was the neighborhood – and it was a thing with life and sentience – knew something was going to happen. The silence made the sweat return. It was too quite.

“He came around the corner, and they were waiting.

“Nobody bugs out on the Cougars,” was all one of them said. It was dark, the streetlight broken, that he could not see the kid’s face, but it was light enough to see the reflection of moonlight on the tire chain in the kid’s hand. Then they jumped him ...”

That is one thing Ellison did, catch the ‘feel’ of the 1950s. It’s got that sort of ‘West Side Story’ with more warts.

I was immediately caught up in more than the story. Ellison was able to take me into the era with vocabulary which oozed the 1950s and city gangs of the time. It was an immersion that at a point or two had me re-reading passages to get my head around what they were actually meaning with the slang. That is was only a few times added to the story, although I will admit had it been more, it would have edged a bit toward tedium in reading a book that was best as a quick excursion back in time.

There is a nice surprise deep into the story that I did not see coming, so that pleases as a reader.

And as I said it was a nice quick read, under 300 pages, so it is exactly what a pulp tale should be.

Now as a writer I have to go back to Ellison’s intro. It was fascinating to get a glimpse at how someone as famous as he is now, got his start.

“In case you might wonder, I began writing it around the tail-end of 1956 and the first three months of 1957. I was drafted in March of 1957, and I wrote the bulk of the book while undergoing the horrors of Ranger basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia. After a full day, from damned near dawn till well after dusk, marching, drilling, crawling on my belly across infiltration courses, jumping off static-line towers, learning to carve people up with bayonets and break their bodies with judo and other unpleasant martial arts, our company would be fed and then hustled into barracks, where the crazed killers who were my fellow troopers would clean their weapons, spit-shine their boots, and then collapse across their bunks to sleep the sleep of the tormented. I, on the other hand, would take a wooden plank, my Olympia typewriter, and my box of manuscript and blank paper, and would go to the head (that’s the toilet to you civilized folks), place the board across my lap as I sat on one of the potties, and I would write this book,” he wrote.

“It was almost a year later, in 1958, while I was serving out my sentence as the most-often-demoted PFC in the history of the United States Army, at Fort Knox, Kentucky, when this book finally hit print. I was writing for the Fort Knox newspaper, and getting boxes of review paperbacks for a column I was doing, when the August shipment of Pyramid titles came in. I opened the box, flipped through the various products therein, and almost had a coronary when I held in my hands, for the first time in my life, a book with my name on the cover.

“Except, the book was titled Rumble.”

“Nonetheless, it was an experience that comes only once in a writer’s life, the first book, and I was the tallest walkin’ Private in the Army that week.”

And then Ellison shows how most writers feel about their first.

“And even if Web of the City isn’t War and Peace, you just can’t kill something you’ve loved as much as I love this book,” he wrote.

Ellison is correct that Web of the City is not a classic book, but it does provide a hint at just how good Ellison would be as a writer since he got far more right than wrong in his book.