In Part I of this two-part series staff writer Thom Barker examines a heart-breaking story of one local family's loss, the history of asbestos use and its link to mesothelioma.

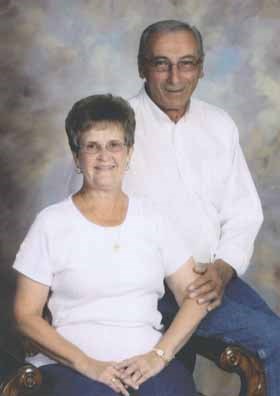

For 37 years, Ernie Sasyniuk was well-known to Yorktonites as the affable and reliable Roto-Rooter man. Last March, at the age of 73, he was still at it when he developed a persistent, dry cough accompanied by fatigue. Initial medical tests were inconclusive, but on a vacation to Victoria in early April his fatigue became so pronounced he spent almost the entire week in bed, recounted his wife Ivy.

More tests eventually led to a diagnosis of pleural mesothelioma, a particularly aggressive form of cancer, the only known cause of which is exposure to asbestos. It is very difficult to diagnose-largely due to its long latency period of 20 to 50 years-and highly resistant to treatment.

Nevertheless, through consultations with Regina oncologist Dr. Torrie, the family decided to give chemotherapy a shot. After five unsuccessful treatments that emaciated the formerly robust businessman, they abandoned that course of action.

With help from Sunrise homecare and palliative care, Ernie made it through a family reunion celebrating his and Ivy's 50th wedding anniversary September 27 and his 74th birthday September 28.

After that, Ernie's decline was rapid. Just eight months after the first signs had appeared, on November 14, 2013, he died.

While those last weeks were difficult, to say the least, Ivy said Ernie was very comfortable and able to spend his last days at home with family largely due to the heroic efforts of homecare and palliative care workers.

"I don't know if I can even explain how great they were," she said. "Every time we called they were here in 10 minutes."

And, she recounted, Ernie kept his famous wit until the very end. Just before the whole ordeal started, he had mentioned he wanted to trim down a bit because he felt he was developing a bit of a belly. The ravages of the disease and its treatment stripped him of 45 pounds.

"Well, I didn't want to lose it this way," Ivy recalled him quipping.

Ancient times

The mineral asbestos has been known for millennia. The ancient Greeks, Romans, Persians and Chinese were enamoured by its seemingly magical properties, particularly, its fire resistance. The name itself comes from the Greek word meaning inextinguishable or indestructible.

The ancients even ascribed mystical properties to it. "Amantius, which looks like alum, is quite indestructible by fire. It affords protection against all spells, particularly that of the Magi," wrote the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder in book XXXVI.xxxi.

Ko Hung, a fourth-century Chinese alchemist, wrote that asbestos was among the most highly esteemed traditional Chinese medicines for "an eternal life."

Ancient peoples used asbestos as a flame retardant cloth and in building materials and pottery to strengthen them. The Eqyptians embalmed their Pharos with it and the Persians wrapped their dead in asbestos cloth.

Some authors have suggested that, even way back then, adverse health effects of asbestos were known citing both the Greek geographer Strabo and Pliny as having noted "the sickness of the lungs" among slaves who quarried and wove the "miracle" mineral into cloth.

Rachel Maines, an American technology historian, disputes this in her well-researched and excellent book Asbestos and Fire: Technological Tradeoffs and the Body at Risk, saying there are no such references in ancient texts. She hints, although does not say outright, that the information is a fiction of litigation.

"Because Pliny and the other ancient western commentators on asbestos play a significant role in the modern asbestos legal debate, it is worth setting forth in detail what these writings actually have to say about the mineral," she wrote, concluding there is no concrete evidence the ancients were aware of bad health effects.

Proliferation

The modern era is another story altogether. Although asbestos saw only limited use in western Europe before about 1700, it was really the Industrial Revolution that served as a catalyst for its widespread proliferation.

Asbestos actually refers to a group of silicate minerals that occur in a fibrous crystalline structure. The fibres are, in fact, extremely slender prismatic crystals. This makes it very fragile and prone to becoming dust, particularly during mining operations. It is pertinent to understand that even at the microscopic level, it maintains its crystal structure. This is what makes it an industrial super-hero and a medical super-villain.

The list of modern uses of asbestos is virtually limitless because of its physical properties. Deposits of the various minerals are widespread and it is easy, therefore cheap, to mine. It does not burn, at least not at temperatures involved in human applications. It does not conduct electricity and does not react with most chemicals, including acids. It is lightweight and has very high tensile strength (much stronger than steel, for example). The long, thin fibres are easy to work with, as evidenced by its ancient uses; it can even be spun into cloth.

During the early Industrial Revolution in the mid- to late-1800s, it was widely used as insulation for steam pipes, turbines, boilers, kilns, ovens, and other high-temperature products.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, asbestos would come to be used in thousands of household products including household insulation, paint, shingles, cement and other building materials, stoves, washers and driers, brake linings, even oven mitts and pot holders.

By the 1930s, the link between asbestos, lung diseases and premature death was already being established, but despite growing evidence of its toxicity, the post-World War II period would see further expansion of asbestos use.

In Canada, it was big business with mines operating in Quebec, Newfoundland, British Columbia and Yukon. High rates of lung ailments and shortened life spans in mining towns led to the four-month, often-violent Canadian Asbestos Strike of 1949. Little, if anything, in the way of safety regulations came of it. By 1966, Canada was producing an estimated 40 per cent of the world's chrysotile asbestos. Today, although its use has been mostly banned domestically-it is still widely used in the aeronautical industry-the country continues to export thousands of tonnes of asbestos to developing nations where workers process it with little or no safety regulations to protect them.

Local risk

During the 1950s and 1960s, Ernie Sasyniuk and hundreds of others involved in the Yorkton construction industry would have been nearly constantly exposed to the hazardous mineral as virtually every home, business and institution were constructed with numerous asbestos-laden materials

"They never even wore masks or anything," Ivy recalled.

They also frequently brought the problem home. The tiny, often microscopic crystals, are perfectly suited to clinging to clothing, skin and hair. One of the fastest growing groups of mesothelioma victims are the spouses and children of men who experienced on-the-job exposure.

Washing their husbands' work clothes, even sleeping in the same bed, would have led to secondary exposure.

Ivy Sasyniuk is obviously devastated by the recent loss of her beloved Ernie. Her voice sometimes cracks and her eyes swell as she tells their story, but she wants to spread the story as widely as possible to alert people to the risk.

And, while Ernie is now at peace, it isn't the end of the family's worries.

"We don't know if I will get it too," Ivy said.

Next week: The disease, its prognosis and treatment, victim compensation and the current state of asbestos policy.