Corporal Chris Lohnes is a dog handler with the RCMP based out of the Yorkton rural detachment. In addition to working with partner Musqua on cases throughout the region, he is also helping develop younger dogs and prospective handlers for the force.

Lohnes explained there are only seven RCMP dogs in Saskatchewan, one dedicated to sniffing out explosives, and the other six covering large areas of the province. In his case, based in Yorkton, Lohnes and partner Musqua cover an area from the Manitoba border to near Humboldt, while traveling north to Hudson Bay, and south to near Carlyle.

"It would be nice to have more. We cover huge areas," said Lohnes.

The large coverage areas are not ideal to the immediacy often needed by the job.

"We work with time challenges," said Lohnes, who can have more than two hours in the truck on route to a track.

Lohnes said it can be a case because of the delay of doing a track where it is less about finding the suspect at the end of the trail, and more about what they find on the track. A foot print, or something dropped by the suspect might be the forensic evidence they can use to find the suspect through things such as DNA.

The six regular dogs in Saskatchewan are broadly trained to cover everything from searching for lost children, to tracking suspects, and in Musqua's particular case has specialization in searching out drugs.

The prospective pups begin training almost from birth, and it is a strenuous training program.

"One in about 250 make it as a police dog," said Lohnes, adding the RCMP do run a strong breeding program at a facility in Innisfail, AB.

"We're having very good luck with our breeding program," he said, noting they use genetics and actual field performance to match up breeding pairs to enhance the chances for pups with the right characteristics to be a police dog.

Once a pup is about two months old it is given to a handler, often an RCMP officer with aspirations of becoming a full-time dog handler, which is what Constable Chris Pshyk is hoping to do. He is currently working with Durc to see if he will have what it takes to make it as an RCMP dog.

"His (Pshyk's) first dog is in Halifax now," said Lohnes. While not having the rounded skill set to be a police dog, he had an excellent nose, so now specializes as an explosives sniffer.

In the earliest stages of training, Lohnes said it is about creating a solid foundation for the dog.

"It's a lot of specialization stuff and familiarization stuff," he said.

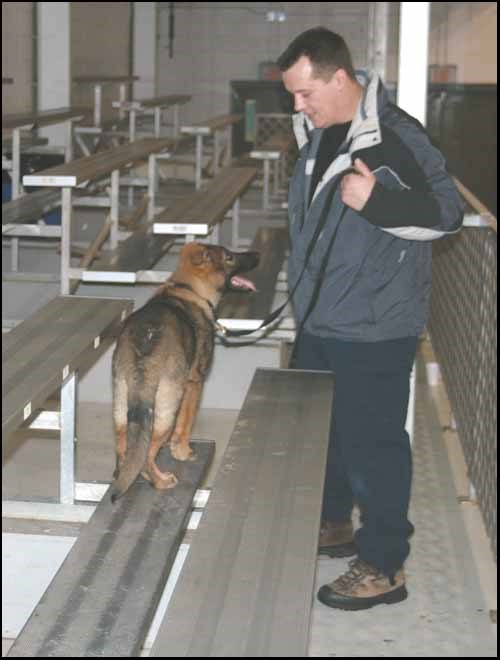

As an example Lohnes said they try to introduce the pup to as many different situations as possible. Thursday, as an example they had Durc getting used to galvanized stands at the Farrell Agencies Arena amid the noise of a Junior Terriers hockey practice.

It's also a case where they want a pup to show retained learning. For example if Pshykc teaches Durc something in Moosomin, where Pshyk is stationed, they want him to take it in stride in Yorkton, and not have to re-learn it here.

Lohnes knows about training and working with a dog. The 25-year veteran of the RCMP has been a dog handler for 17-years, and is about to train his sixth partner this year, since current dog Musqua is nearing retirement at age nine.

"He's had a pretty hard working life," he said, adding he deserves retirement.

Saying good-bye to Musqua will be difficult.

"It's not easy," said Lohnes. "It makes it easier when you find really good people to pass your dog on to."

Lohnes said it takes an owner that understands the animal was a working police dog, so he will be scenting trails on walks, and will be protective if someone acts up around the new owner.

"If somebody does something stupid around you, the dog is going to make contact," he said.

The process of developing a dog handler is even more arduous for the officers involved.

They spend time as 'quarry' before even getting to work directly with a dog.

"I help train Chris' (Lohnes') dog (Cody at present)," said Constable Nicholas Popovic, based in Yorkton.

The help includes everything from going ahead of the dog laying down 'evidence' he must find, to being a suspect on the road, knowing he will eventually be tackled by the German Shepherd, and hoping to protective arm guard takes the brunt of the attack.

"You're the bait," said Popovic. "You go into a building and hide you lay a trail." It is then up to Lohnes and his dog to search out the 'suspect'.

Next comes being assigned a puppy. Pshyk is at that stage. He has to raise dogs for at least two years before getting a chance to progress to actually training with a mature dog.

Lohnes said it's a process which creates a foundation for the handler. They get to know what is expected of the position, and how to understand what the dog is actually doing when working. He said handlers need o recognize traits in a dog which are indications of what he is doing, like the reaction to picking up a trail, or sensing something out of the ordinary.

It's also about teaching the handler. Lohnes said a handler must really take in the big picture of a scene, and not get too tied to watching the dog. For example the handler needs to see the road ahead and be aware of how he and the dog can cross it safely, or he needs to see a building ahead and be aware a dangerous suspect might be hiding there, and so approach it as safely as possible.

"You really have to broaden your senses," he said.

So why would officers want the extra work and training needed to be a dog handler?

Pshyk and Popovic say it really goes back to their love of dogs.

"I've always had dogs. I grew up with dogs," said Pshyk. "I think you have to enjoy working with dogs. You have to have an aptitude with them You have to have the patience and desire to work with dogs."

Popovic echoed the sentiments.

"I've had dogs pretty well my whole life," he said, adding he likes the idea of working with a dog as a partner. "You take your dog to work, and then take him back home. He becomes part of your life."

That adds to the responsibility of the position, noted Lohnes,.

"It's not so much a job in the RCMP, it's a lifestyle," he said.

For example, even if it's Christmas day Lohnes has to run his dog Musqua.

"They're part of the family, but also a working dog," he said.

Lohnes said the position is not for everyone.

"You have to be really self-motivated, and self-reliant," he said.

It can be a job calling for patience too. Lohnes said you can spend literally days crisscrossing a field helping the dog find the proper scent trail to follow.

"It can take three days to find something," he said.

Lohnes said at present the force is in need of new handlers. Of the 150 stationed across Canada "we have probably half of the handlers who could retire tomorrow if they wanted too," he said. "There's a lot of senior guys in the section."

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)