YORKTON - It is without a nanosecond of hesitation that I say Paul Henderson’s goal in the last minute of the 1972 Summit Series is the greatest moment in Canadian sports history.

The entire eight game series captured the imagination of almost everybody in this country, with our collective psyche battered by the then unknown Soviet team dominating the first four games in Canada.

And, then when the series moved to Moscow, it got worse as they won game five.

It was a gut punch to the nation.

But then Paul Henderson, something of a workman-like player in the NHL went into an imaginary phone booth somewhere in Moscow and emerged a superhero, scoring massive goals in the final three games, including the iconic series winner. In the process he salvaged the series and restored our faith in our hockey heritage.

I was 12, in shop class at Centennial Junior High School watching on television when Henderson scored, and I still recall the emotion, the exuberance of the moment, even now 50-years later.

That it was 50-years ago seems impossible given the vibrancy of the memory, but it has always been one of our proudest as a nation.

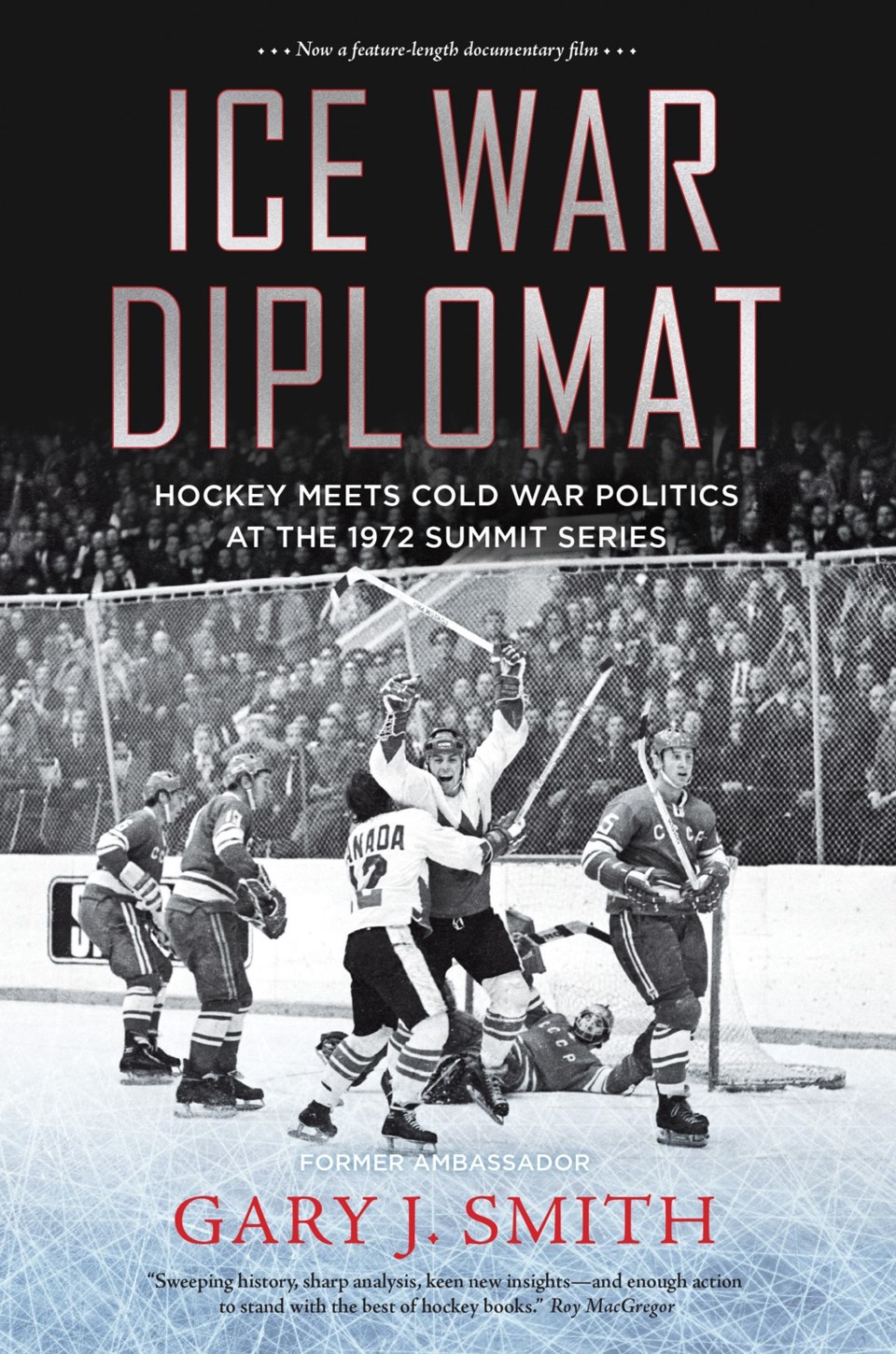

So now, a half century later it’s not surprising the series is being marked by a number of new books. One of those is Ice War Diplomat by Gary J. Smith.

Smith pens the book from a very different perspective, that of a young Canadian diplomat in Moscow who would end up being at the table of many of the negotiations leading to the series even happening, and then being in the rinks for all eight games.

As a story which takes you behind the scenes of diplomatic talks there was a chance this book could have been dry, written too much like a diplomatic report.

But, Smith stickhandled around that pitfall like Yvan Cournoyer in the series, and wrote a book rich in unique insights – the member of the Russian delegation wanting to see The Godfather, another seeking a veterinarian for a medicine for his dog not available in the Soviet Union at the time, to the ‘swallows and ravens’ Russian women offering ‘comforts’ in hopes of gathering information, while still managing the highlights of the series.

“When I started ... I asked who was the reader?” Smith said in a recent interview with Yorkton This Week. “It wasn’t for a bunch of bureaucrats in Ottawa. It was for the average Canadian. I’ve got to make this exciting.”

Mission accomplished on that for Smith.

But how did Smith manage all the detail a half century later?

“My memory’s still pretty good,” he said, but added he didn’t leave it to memory, delving into boxes filled with files in Ottawa, many he had himself penned back in 1972.

That was one of the intriguing aspects of the Summit Series, it was very much the creation of government at the highest level.

“They had been working on this for years and years and years,” said Smith, adding all the efforts by hockey organizations to get a team of Canadian professional players on the ice against the powerhouse Soviets had failed, even as Canada pressured by pulling out of World Championship play.

Then Canada and the Soviet Union signed a General Exchanges Agreement the door to facilitate the series.

“Among the prime minister’s briefing papers, there had been a confidential note prepared by External Affairs about Canada – Soviet hockey relations, with five paragraphs of “talking points” to raise with the Soviet premier, either formally or informally. It was similar to what had been prepared for his visit to Moscow. The first sentence stated the obvious: “One of the most important channels of contact between the people of Canada and the Soviet Union has been international hockey competition.” The final paragraph referred to the efforts of Hockey Canada and the CAHA, with the Soviet Sports Committee and Ice Hockey Federation, to find a solution to the current impasse. The last sentence of the paragraph stated, “This should be encouraged at the government level by both Canada and the USSR to mutual advantage,” wrote Smith in the book.

Overall, the book is a gem, for its honesty too.

We reveled in the win in 1972, but as the book brought into focus more than I would have realized as a 12-year-old, there were elements of the series Canadians should have felt shame over too.

“Meanwhile, Bobrov – and it seemed everyone else in the USSR – now had a public enemy number one in the form of Bobby Clarke, a slashing poster boy for everything that was wrong with ‘hooliganism’ in Canadian hockey. Despite Yakushev’s comments after game five, many Soviet observers would say the crippling of Kharlamov was the real turning point of the series. The incident stuck in the minds of Russians for decades afterwards. One subsequent Canadian ambassador who served in Moscow in the early 1990’s said that in some circles it was equated with dark events like the 900-day German encirclement and siege of Leningrad during the Second World War,” wrote Smith.

Imagine had that happened to Henderson or Phil Esposito?

But, it was still an event so Canadian it has never left our memories.

“Thursday, September 28, 1972, had been a momentous day for Canadians. While Henderson’s goal was scored during the evening in Moscow, it had been midday or earlier in Canada. Workers across the country had laid down their tools, telephones and order books, students put aside their studies, all to gather in front of television sets for the rare shared experience of watching game eight. A coming together of national anticipation. Not just a sporting moment, but a defining cultural event of “where were you when” dimensions. Like the US astronauts’ moon landing on July 20, 1969,” writes Gary J. Smith.

Yet, it might be a Soviet star who best summed up the series Smith captures so well in Ice War Diplomat.

“The Russians on the other hand were always happy to celebrate a positive occasion, and they considered 1972 not as a defeat, but as a spectacular event in which “both sides won.” “Hockey itself was the victor” went the claim, often stated by Vladislav Tretiak, who at this point was the president of the Russian Ice Hockey Federation,” writes Smith.