YORKTON - When it comes to hockey I’ve been a fan for as long as I can recall.

There were Topps hockey cards and Esso sticker books, and a newsletter from Scotiabank Hockey College and of course watching Hockey Night In Canada (HNIC), with my dad – all were things of my childhood.

And oh yes I did shoot a few hundred slapshots off the front of the barn, sometimes using a puck, sometimes an orange hockey ball, and sometimes in lieu of either a junk of frozen manure.

Dad was a Montreal Canadiens fan – proving I suppose that even dads can have flaws.

With him cheering for the Habs, I of course could not, so opted for Toronto, the only other Canadian team at the time, and one we saw often on HNIC.

Sadly, the Leafs weren’t very good after their 1967 miracle win, so my young eyes did wander to the Boston Bruins for a short time; lured by the likes of Bobby Orr and Derek Sanderson.

Of course Dad held bragging rights most years, the Canadiens being almost perennial Cup winners.

Even in years they weren’t supposed to win, they often did.

Such was the case in 1971, a year an unlikely assemblage in Montreal won the Stanley Cup yet again.

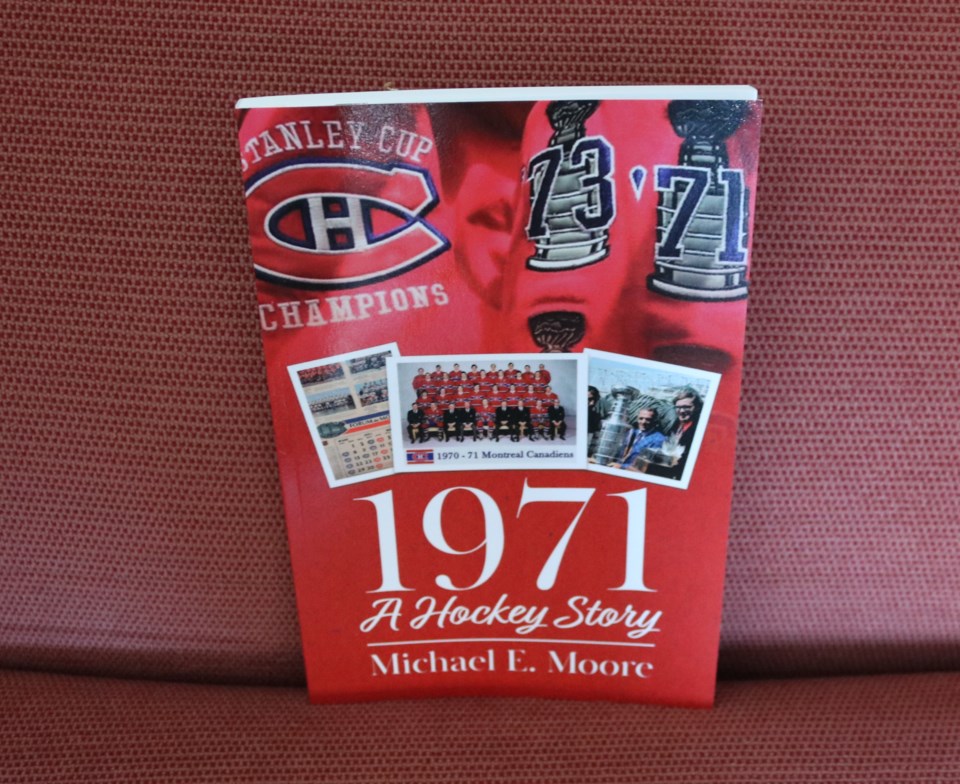

It is the stuff of legend and legends make good books, and author Micheal E. Moore took that to heart in producing 1971: A Hockey Story.

Surprisingly Moore doesn’t count himself a diehard fan.

“To be honest I’m not a great fan, I’m more of a fair weather fan,” he told Yorkton This Week, adding the current edition of the team is hard to watch. “They’re not the traditional Canadiens I grew up with.”

The days he refers too saw the Canadiens win 10 Stanley Cups in 15-years, a feat likely never to be repeated.

“We were spoiled in those days,” admitted Moore.

It was a hard read in the sense I could too often see a glimpse of my Dad with a wry smile after another Montreal win, especially in the playoffs when I was cheering hard as an 11-year-old for the Orr –led Bruins. I admit I cried when they lost.

Moore said the 1971 team stood out in many ways, particularly finishing third and then topping both the Bruins and Blackhawks on the way to the Cup, winning as underdogs to both.

“Being the underdogs put the team in a different position, and fans in a different position,” he said,

But, given the storyline, this was also a good read in the sense I recalled all the players on the Canadiens and their foes, as well as the era, albeit some of it more from history class come junior high than following it live at age 11.

For example; “in the fall of 1970, the city of Montreal experienced terrifying events, some of the worst in its long history. Like WWII provided the backdrop of Casablanca, the October Crisis, which coincided with the beginning of the 1970-71 NHL hockey season, was a threatening and unsettling upheaval. The tragic events were mostly concentrated in Montreal. The Front de Liberation du Quebec (FLQ) were militants who used terrorism to promote and achieve Quebec sovereignty. They detonated bombs across the city, including the Montreal Stock Exchange, and their violent actions culminated with the kidnapping of British Trade Commissioner James Cross on October 5 and Quebec Minister of Labour and Minister of Immigration Pierre Laporte on October 10. Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act, a law that gave government and police extraordinary powers, and the army marched in. The city was under siege. People were scared,” writes Moore.

It is always interesting to remember sport does not exist in a vacuum separate from the world around it, but it does act as something of a safe haven from the worst of things, a place to escape too and simply enjoy the game.

The book also sheds a light on just how different hockey was a half century ago.

“The Canadiens paid their first visit of the season to Boston on November 8. It quickly deteriorated into a brutal bloodbath as one of the nastiest bench-clearing brawls in Boston Garden history broke out at the end of the first period. Not only were there an assortment of bouts at mid-ice, but Derek Sanderson of the Bruins and Phil Roberto of the Habs also began a skirmish at the Canadiens’ bench. Soon, the Boston Police became involved as hostile Bruins’ fans started taking swings at Roberto. This mayhem just about degenerated into another all-out Boston tea party.”

The book goes on to note, “by the end of the calendar year, NHL President Clarence Campbell had levied more than $15,000 in fines to various teams for five bench-emptying affairs, three of which involved the Montreal Canadiens . . .

“Skull fractures, broken jaws, blood-letting and an average of three hundred stitches per team, per season, were the norm in the NHL of 1971.”

The players too somehow seemed tougher too, or maybe just willing to risk careers on playing when they probably should not have.

“The Habs got some unwelcomed news soon after game one. Defenseman Jacques Laperriere had a broken wrist. It was only disclosed after the series was over. With Serge Savard out for the season, the Canadiens could ill-afford to lose Lappy, so they taped it up, strapped it and froze it, and Jacques played the rest of the series in pain but like a champion. He didn’t miss a shift, but the Canadiens certainly missed his booming slap shot. He contributed 13 points and played in all 20 of the Habs’ 1971 playoff games. Others were banged up too. John Ferguson had a torn muscle above his left hip that was causing so much pain and trouble, he had to have it frozen three times a game. It only hurt when the novocaine wore off,” writes Moore.

And similarly, “it was the Blackhawks’ turn to get a dreadful scare in game two. The Canadiens were buzzing around the Blackhawks’ net when Rejean Houle was upended, razor-sharp skate blades exposed and flying everywhere. Defenseman Pat “Whitey” Stapleton slid into the scramble and almost swallowed the back of Houle’s skate. Instead, it entered Whitey’s mouth on an angle, pierced his cheek from the inside out, and slashed the outside of his face up to his right ear. Blood poured out everywhere. Chicago trainer Skip Thayer rushed to the scene as fast as possible. Stapleton grabbed the towel and headed off immediately. He was rushed to the hospital and met by a plastic surgeon who performed a mammoth sewing job of 104 stitches to repair and restore Pat’s facial features. He was leading the 1971 playoffs with a plus-22 at the time. Along with defense partner Bill White and Bobby Hull, he was averaging 40-45 minutes of ice time per game, so the Blackhawks could not bear to lose him. Stapleton returned and was ready for game three of the finals on May 9 in Montreal. He wore no additional face or head protection.”

As for the big win, it made the name Ken Dryden a household name in Canada. He was the surprise playoff starter in net, a goaltender virtually untried at the NHL-level, He would go on to win the Conn Smythe Trophy as playoff MVP.

“By now Ken Dryden had become a household name with kids across Canada, especially in Montreal. Overnight, he had become their idol. Young goalies in the minor leagues learned and adopted the “Dryden pose” as they rested their chins on arms folded across the tops of their goalie sticks during play stoppages,” Moore wrote.

Moore said Dryden is clearly the player “people tend to remember,” but the team really won as a team with key contributions up and down the line-up.

Frank Mahovlich led the team in scoring, a midseason pick-up happy to be in Montreal.

Jean Beliveau in the last year of a storied career was a leader.

Henri Richard scored huge goals.

And the list goes on, and in the end the depth showed. Ten players were destined for the Hall of Fame.

Moore said in the end it a season he always had fond memories of having watched the season as a young teenager.

“They were down in so many crucial games and always came back,” he said, noting they trailed Chicago in the final two-games-to-none, winning in seven in Blackhawks ice after trailing that game 2-0. “. . . They just kept coming back.”

The book was one Moore said he has long thought about.

“I always wanted to write a book, and knew this is what it was going to be,” he said. “. . . I grew up with 1971 in the back of my mind.” It is a Canadiens’ tale “. . . That has endured for 50 years.”

The book is available through Chapters/Indigo online or Amazon.