YORKTON - Where were you in ’72?

That’s catchy enough I’m surprised it’s not a t-shirt right now given the interest in answering that question for those of us old enough to have memories of the famed ’72 Summit Series.

The series pitted Canada against Russia in the greatest hockey series ever played – yes it’s not even close enough to be debated for me.

Canada was supposed to win all eight games, a cakewalk that would barely have greats like Phil Esposito and Yvan Cournoyer, Ken Dryden, Brad Park and all the other NHL greats barely breaking a sweat.

But, no one told the Russians that they were to lose in an easy sweep, and it became a war on ice, one that shook Canada’s pride in the game, brought a country together, saw heroes rise, and in the end the biggest moment in Canadian sport emerged.

Paul Henderson was the great hero, and his dramatic goal in game eight on Sept. 28, 1972 is one where a replay on TV still raises the hair on the back of my neck, the hairs of course now gray a half century later.

It was that way for many.

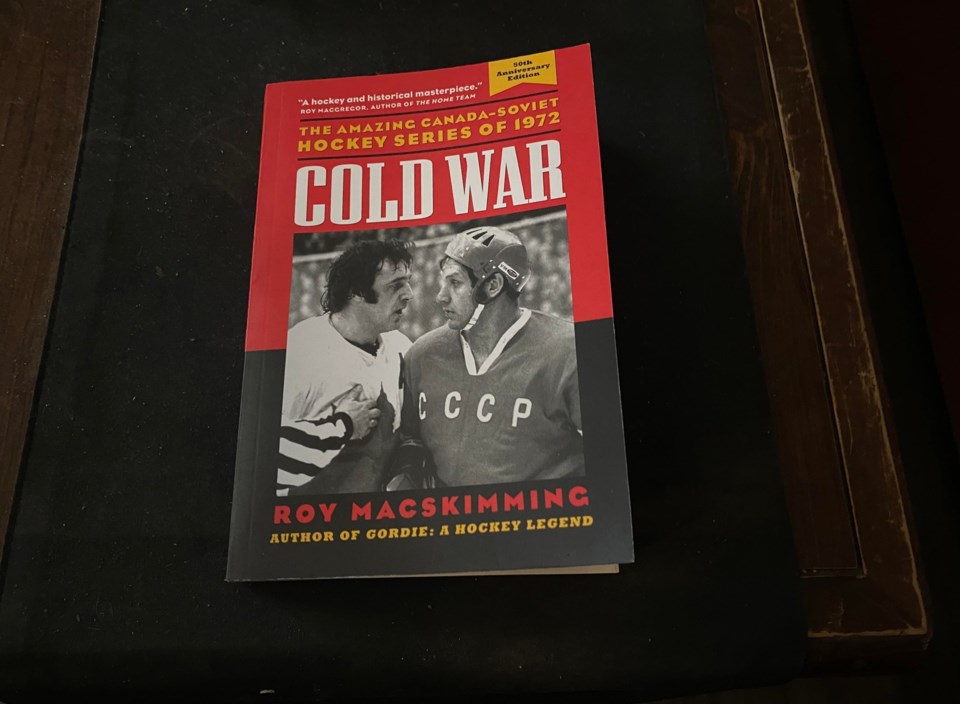

Author Roy MacSkimming talked to a number of people about their memories for his book Cold War.

“Dave King was teaching high school biology and physical education in Saskatoon back then, as well as coaching Junior B hockey. The classrooms at his school all had TV sets going that day, all showing the same thing. “The teachers felt it was important for the kids to see that last game. Our hockey heritage was on the line, so it was a major Canadian event. Even the girls and the non-hockey fans got caught up in it. After Henderson scored, all the classroom doors opened out onto the corridor, and the kids just came pouring out – it was incredible.”

And then there was “Verne Clemence, for example, then Sports Editor of the Enterprise in the small Saskatchewan city of Yorkton, was in the process of writing his column for the next day’s paper,” wrote MacSkimming. “When Team Canada went into the third period two goals down, I’d given them up,” Clemence remembers. He’d been powerfully impressed by the Soviet team throughout the series, and his column contained some comforting philosophical observations about how superbly the Soviets played, and how it’s only a game, so let’s not get too excited about losing. “But we were having a hell of a time getting the paper out, because there was an Eaton’s store two doors down, and they had TV’s going in the window and inside the store. All the guys from the composing room kept slipping out to watch the hockey game, so we were getting further and further behind. Finally, the publisher said, ‘What the hell, let’s go,’ and we went too and watched the last few minutes of the game at Eaton’s. Everyone was getting pretty tense, but when Henderson scored, a great cheer went up. I went back and rewrote my column. I was pretty excited about being on the winning side after all.”

MacSkimming stayed in Saskatchewan for one more.

“For aspiring young novelist Guy Vanderhaeghe, living not far Clemence in that hockey-mad province, the series began and ended with weddings,” he wrote. “The first was his own, which took place September 2, 1972, the day of Game 1. During the reception in Esterhazy, Saskatchewan, Vanderhaeghe learned that Team Canada had scored two early goals, and all was right with the world. He and his bride, Margaret, drove off in a radio-less car for their honeymoon in Kindersley. By the time they arrived, the game was over, and Guy was absolutely shocked to be told Canada had lost 7-3; his world had changed, in more ways than one. On the day of Game 8, Vanderhaeghe’s former roommate got married in Arborfield. After the bride and groom departed, Vanderhaeghe recalls, “ten of us men, mostly total strangers, huddled on sofas and chairs to see how the series would end. My roommate’s father, who’d always hated the Montreal Canadians, suddenly found himself ecstatically cheering ‘Cornbinder’ for tying the game 5-5. By the time Henderson scored. It was if we’d all known each other forever.”

Since 1972 the series has been written about throughout the years, including MacSkimming’s Cold War first released in 1996 on the eve of the 25th anniversary of the series, and now re-released for the 50th.

“When the hockey teams of Canada and the Soviet Union faced off against each other in 1972, they would change the game forever. Weaving together rich period detail, illuminating anecdotes, and thrilling hockey action with eyewitness accounts from Paul Henderson, Ken Dryden, Harry Sinden, and other series greats, author Roy MacSkimming evokes as never before those twenty-seven legendary days in September 1972,” notes greystonebooks.com.

What makes this book interesting is that the anecdotes while gleaned from interviews a quarter century ago remain relevant as history – perhaps being even sharper memories as another quarter century have passed.

“It’s not a brand new book, but it’s still very relevant,” said MacSkimming in an interview this week.

“Their meeting in September of that year would be an unprecedented, primordial event. In the context of hockey, it would resemble the first contact between Europeans and the New World, a moment of profound revelation and impact. Throughout Canada, it created more sustained anticipation, excitement, anger, angst and ecstasy than any other sporting event in the country’s history – indeed than any event of any kind since the Second World War had ended twenty-seven years earlier,” MacSkimming wrote in the book’s introduction.

“. . . And it did more. By sharing in the enactment of the myth, Canadians – temperamentally so fractious and resentful a people, then as now, on grounds of language or region or ethnicity – joined together in a rare moment of unity. By surrendering to a process larger than ourselves, we transcended the pettiness of our usual concerns. By going so deeply into our national psyche, we were briefly able – ironically – to travel beyond our habitually narrow frame of national reference. The 1972 Canada-Soviet series swept us into a wider world, and in the end it changed us; we learned something vital about who we are, and where and what we’ve come from. It was an odyssey from innocence to experience.”

So it is easy to understand why Canadians 60 and over recall the series so keenly, they watched it living and dying with every goal.

Sixteen million out of a Canadian population of 22 million in 1972 watched game eight – of 73 per cent of people in the country, said MacSkimming.

No other event had so captured the country before, he added, suggesting it was like two worlds colliding the hockey of two nations who had never really played each other before with a best-on-best series.

And it was more than hockey with Canada defending democracy against Russian communism.

MacSkimming said he chose the title Cold War because of its double meaning, hockey on ice and the conflict of ideologies.

MacSkimming said one reason the series has stayed of such high interest is the impact those eight games had on North American hockey.

While Canada eked out a win, it was obvious European hockey was at a very high level, frankly better in certain aspects, and that led the game to evolve here.

It also opened the door to Europeans in the NHL.

In 1972, 98 per cent of players in the NHL were Canadians. Today they remain the biggest source of talent but at around 45 per cent, said MacSkimming, with Americans making up 26 per cent, Swedes 10 per cent and the rest of Europe contributing the rest.

In Cold War MacSkimming even has a chapter focused on where hockey has gone since the Summit Series.

“There was a tremendous impact,” he said.

So had Canada swept as many expected would the evolution of the game been slowed, the influx of European players slowed?

“Maybe,” said MacSkimming, adding there was a belief going into the series “our system was better,” but in barely winning the Canadian game learned it was not as superior as believed.

But in the end we had won, and oh it was glorious.

“The puck ricochets off the boards in the left corner,” wrote MacSkimming. “No fewer than three Soviets are near it as it comes bouncing out to them. Yet unaccountably, they all hesitate, as if thinking to leave the puck for the other guy. None of them takes charge, none of them takes possession. Both Vasiliev and Liapkin touch the puck briefly but mishandle it. Trailing on the play, Esposito is the first to reach the loose puck. Unhesitatingly, he shoots at Tretiak from twelve feet out.

“Tretiak blocks the shot easily with his stick. But he allows a rebound, and suddenly Henderson, who has scrambled to his feet behind the net, thinking the Soviets will clear the zone now and he’ll have to skate all the way back to his own end before getting one last chance to score, is all alone with the puck in front of Tretiak. Henderson shoots – Tretiak makes a pad save and sprawls on his back, and again the puck comes out to Henderson. Henderson shoots again – a low slider aimed straight at the narrow space between Tretiak’s body and the right post – and incredibly, the puck is in the net!”

While a number of books have been released on the series, a trio previously written of here; Ice War Diplomat by Gary Smith, 1972: The Series That Changed Hockey Forever by Scott Morrison, and The Greatest Comeback: How Team Canada Fought Back, Took the Summit Series, and Reinvented Hockey by John U. Bacon, the re-release by MacSkimming is most assuredly a worthy tome recounting the series.