MONTREAL — The ground search to find two missing Quebec girls who were later discovered killed by their father came "too little, too late," a Quebec coroner has concluded.

In a report released Tuesday, Luc Malouin said the 2020 search for Romy and Norah Carpentier was marked by numerous delays by police decision-makers who failed to fully grasp the urgency of the situation.

Early on, he said provincial police erred in not quickly launching a ground search for the young girls after they and their father mysteriously went missing after a car crash on the evening of July 8, 2020.

"Land research by competent personnel trained to do so, in our case, can be summed up in four words: too little, too late," Malouin wrote in the report.

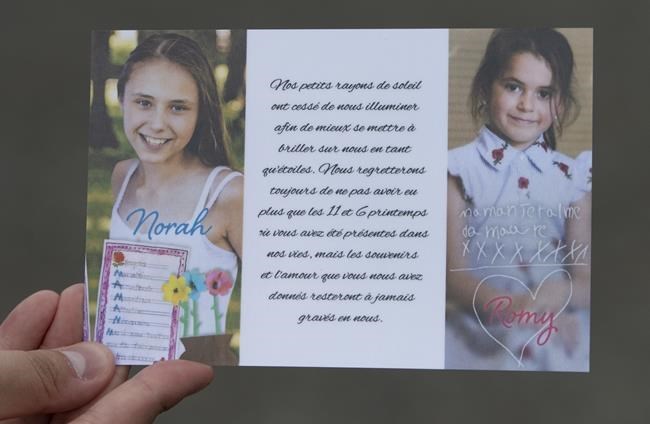

After crashing his car on Highway 20, Martin Carpentier fled the scene and later killed 11-year-old Norah and six-year-old Romy in the woods near St-Apollinaire, Que., southwest of Quebec City. He then killed himself.

The search for the girls and their father turned into a multi-day police manhunt that gripped the province. However, questions quickly emerged about the quality of the police investigation, which led to a public inquiry presided by Malouin between February and May of this year.

While witnesses told police after the crash that Carpentier was a good and loving father, Malouin said they also suggested he'd been struggling with depression, was scared of losing custody of his daughters and his behaviour was out of character.

Malouin said that should have been enough for police to call an emergency response team and launch a ground search at first light. Instead, the call was only made the next morning, and the search only got underway at about 10 a.m. — five hours after sunrise.

Police protocol clearly dictates that disappearances of children under the age of 13 are to be treated as "worst-case scenarios," he wrote, meaning "all the resources should have been in place to carry out the investigation" more quickly. Malouin said a lack of planning, a shortage of qualified personnel and communication errors hampered the early efforts.

Some of the witness statements taken by officers in the early stages were not passed on to subsequent investigators, including a statement by a friend who told police he believed Carpentier kidnapped his daughters for fear of losing them.

The coroner noted that staff shortages were "a constant source of problems" that created delays. However, he said provincial police could have asked for help from other agencies, such as the Quebec City police, the provincial Wildlife Department or qualified volunteer search-and-rescue groups.

He also criticized police for not alerting the media first thing on the morning of July 9, which could have yielded valuable information from the public.

Despite the flaws in the investigation, Malouin said it's unclear whether even the best-organized search would have been enough to find the girls alive.

"The chances of finding them safe and sound would have been maximized, certainly, but it's uncertain whether that could have been the case, to the extent that a hunted man like Mr. Carpentier could have hastened his action," he wrote.

Carpentier was described in the report as a construction worker with "no particular history" and no criminal record who was, by all accounts, a doting father. However, witnesses told the inquiry he had become increasingly anxious and stressed due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the fear of losing custody of his daughters in upcoming divorce proceedings from their mother, whom he'd been separated from for several years.

Malouin said he believes the car crash, while accidental, was the "tipping point" for Carpentier's actions.

"In his panic, he fled with his daughters and it was only over the next few hours, gradually realizing the untenable situation in which he had placed himself, that the idea of killing his daughters before ending his life subsequently came to him," he wrote.

Police have been repeatedly questioned over the fact that an Amber Alert for the missing children was not issued until 3 p.m. the day after their disappearance. Malouin said that while broadcasting the alert was delayed by a technical problem, it was unlikely to have yielded results in the Carpentier case. He noted the issues with the alert system that were present in 2020 have since been resolved.

Public Security Minister François Bonnardel told reporters on Tuesday that the province would work with police to implement the coroner's recommendations, including better training.

"I think the findings are clear," he said in Quebec City. "The time, the few lost hours, sometimes we just talk about three hours, four hours, five hours, but five hours can make a difference."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Oct. 24, 2023.

Morgan Lowrie, The Canadian Press