ROTHERA RESEARCH STATION, ANTARCTICA — A Calgary researcher who has spent the last eight months in Antarctica studying sea ice says he has seen first-hand how big an effect climate change has had in the region.

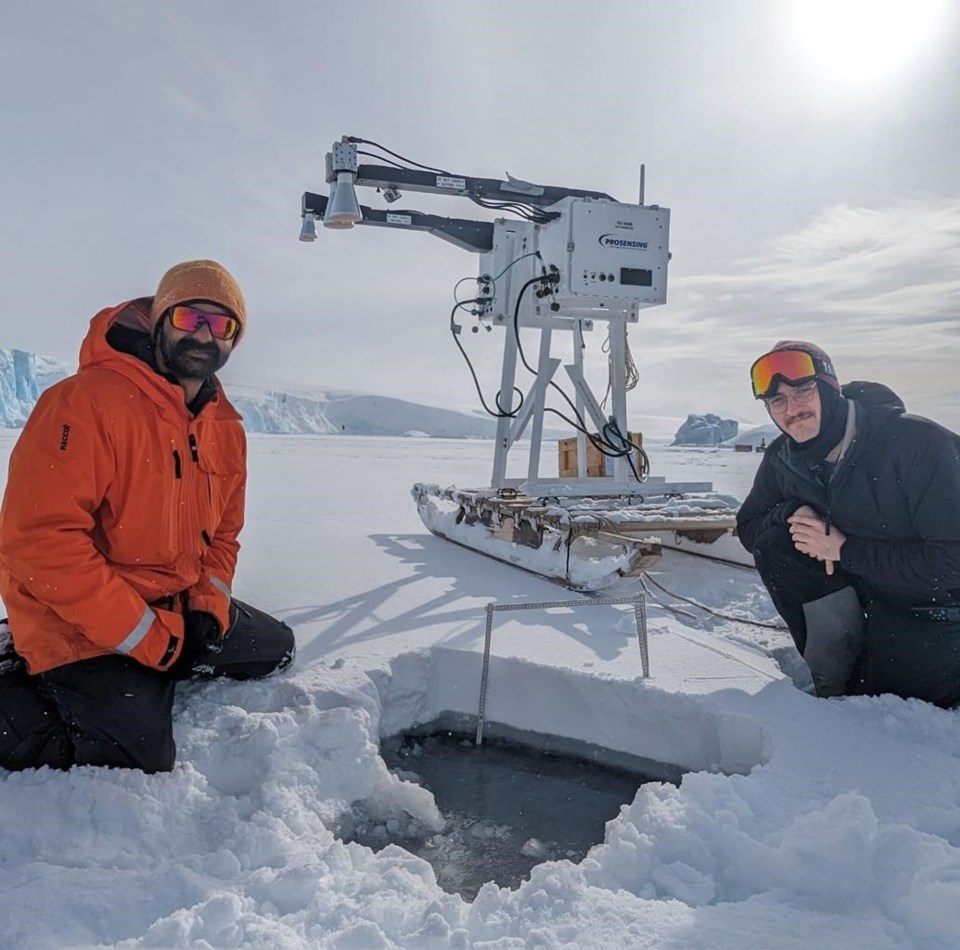

Vishnu Nandan, a post-doctoral associate with the University of Calgary, along with Robbie Mallett, from the University of Manitoba, have been studying ways to improve how radar satellites measure the thickness of Antarctic sea ice and snow.

The research is part of a British-based project called DEFIANT — Drivers and Effects of Fluctuations in sea Ice in the ANTarctic — which aims to deploy a state-of-the-art ground-based radar system that mimics the satellites in space.

"We actually came knowing we wouldn't have a lot of sea ice, because it's been really warm," Nandan said in a phone interview from Rothera Research Station on Adelaide Island, nearly 1,900 kilometres south of the Falkland Islands.

"We came in where we had the lowest sea ice on record over the past many decades, so we didn't have sea ice much and we had really thin ice in the winter."

Nandan said the issue is that the area gets so much snow, sometimes up to a metre, that it's difficult to get accurate satellite readings of snow and sea ice thickness.

They've been collecting data from the ground-based radar system to account for errors and correct satellite algorithms to produce accurate measurements critical for climate change projections.

Nandan did similar research a few years ago in the central Arctic Ocean, when he was on an icebreaker for a year in an extended examination of global warming from a vantage point close to the North Pole.

"Arctic sea ice has declined substantially — about 70 per cent over the past 30 to 40 years. When compared to that, the Antarctic has been stable, but over the past few years, since about 2016, we have seen a dramatic decline in sea ice in many regions across the Antarctic," Nandan said.

"Right now it's serious. It's really bad. If you look at the overall area of the sea ice, the area is almost one million square kilometres less than the previous lowest which was in 1986."

Although there has still been lots of snow, there were several days of rain, which is unusual, said Nandan. He added that the warm wind is preventing the ocean ice from freezing solidly.

He said his research, which is also supported by the University of Manitoba, is important considering what can happen with declining sea ice.

"Sea ice is white in colour and reflects most of the sunlight that is hitting it," he said. "If you don't have enough sea ice, that means there's a lot of open ocean, which is actually absorbing most of the sunlight."

In turn, Nandan said that makes the polar oceans warmer, which can affect both the ecosystem and the weather.

"You get more climate disasters like tornadoes, cyclones, extreme weather events like cloudbursts," he said.

“It effects the ecosystem, from polar bears, phytoplanktons, to animals like seals who need sea ice for their habitat."

Nandan has completed his stint in the Antarctic and will be returning to Calgary next month.

— By Bill Graveland in Calgary

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Oct. 21, 2023.

The Canadian Press