BURNABY, B.C. — Myles Gray's airway was swollen and there was blood in his mouth and throat as an advanced life support paramedic inserted an intubation tube in an effort to revive him after a beating by several Vancouver police officers, the first responder said.

It took two attempts to get the tube down Gray's throat, Stephen Shipman testified Tuesday at the British Columbia coroner's inquest into the 33-year-old's death.

Gray died in August 2015 after the beating by several officers that left him with injuries including a fractured eye socket, a crushed voice box and ruptured testicles.

Shipman told the inquest he initially thought Gray was not a white man because of the bruising evident on his face and parts of his body.

He was badly beaten regardless of circumstances, the paramedic said.

Of the 14 Vancouver police officers who have testified so far, most have said they didn't notice any injuries besides redness on Gray's face and some body bruising.

Several other first responders who saw Gray in the moments before and after he stopped moving also described the bruising and discoloration they observed on Gray's face as police officers rolled him over to begin administering CPR.

Retired paramedic Ross Mathieson appeared via video conference, testifying that Gray appeared to be "cyanotic," with his face turning blue, a sign of a lack of oxygen.

Burnaby firefighter Travis Nagata also told the inquest he recalls Gray's face was blue around his ears down to his chin as officers rolled him over.

Gray's "swollen, purple eyes" stand out in Nagata's mind, he said.

When it became clear Gray was in cardiac arrest, Nagata said heand another firefighter ran to get their medical kit and set up a defibrillator and oxygen.

Nagata said he noticed "quite a large amount of blood" inside Gray's mouth when he opened it to insert an airway-clearing device.

Another Burnaby firefighter, Scott Frizzel, testified that Gray was "quite badly bruised" and looked like he'd been in a "battle."

Retired Burnaby fire captain John Campbell also told the inquest he noticed bruising around Gray's eyes and along the sides of his neck.

When Campbell first arrived at the location where police had been struggling to handcuff Gray, he said an officer told him to wait while the scene was secured.

The officer assured him police would monitor Gray's condition, he said.

It's common for police to instruct firefighters to wait a short distance away if there's still violence at the scene of an arrest, he said.

When he did see Gray, Campbell said the man was lying face down, handcuffed with a strap around his legs, but still struggling as officers told him to stop.

Campbell testified that Gray suddenly became motionless.

He said police then removed the handcuffs and rolled Gray over to begin first aid, before firefighters and later paramedics took over and performed CPR.

The first responders tried to revive Gray for about 40 minutes until he was pronounced dead at the scene, Campbell told the inquest.

He agreed with a lawyer for the police department that he believed Gray's breathing was not impaired in the moments before he stopped struggling.

Another Burnaby firefighter, Lt. Young Lee, said an officer led him to the yard where Gray was handcuffed and struggling as police held him down.

Lee testified that one of those officers said firefighters couldn't yet move in to assess Gray’s condition because he was still "combative."

The firefighters' operational guidelines indicate they are not to treat a patient until police have said the scene is secure, said Lee, who instead walked around the yard to get a better look at Gray from a distance of about three metres.

Lee said one officer had a hand on Gray's head, while a second used his chest to hold Gray's torso down, a third was pressing down on the back of Gray's legs and a fourth officer was holding the end of a strap that was used to restrain Gray's legs.

Soon after Gray stopped moving, Lee said his partner ran to get their defibrillator and oxygen kit as police began chest compressions.

He said the defibrillator did not find a heart rhythm that would have prompted firefighters to shock Gray.

Shipman said he arrived after Gray had already gone into cardiac arrest.

He said paramedics administered drugs including epinephrine and used a heart-monitoring machine, at one point thinking they may have detected a faint rhythm.

They tried a process aimed at helping the heart to beat, but Shipman said he eventually called a doctor and together they decided to stop resuscitation efforts.

Shipman also told the inquest he'd asked police whether Gray had been choked, and officers said they didn't use that term anymore.

He agreed with a lawyer for Gray's family that he'd never heard the term "lateral neck restraint" until it arose that day.

The first responders' testimony came after 14 police officers explained their roles at the inquest that began on April 17, from the first to respond to the initial 911 call to those who attended to a call for backup and joined in the struggle to handcuff Gray.

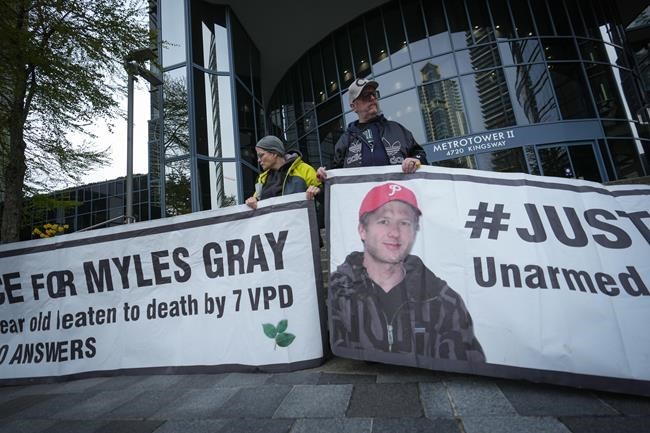

Gray's mother, Margie Gray, told media outside the inquest Tuesday that it was "rage-inducing" listening to the officers' testimony, saying they're all sticking to the same narratives.

"But listening to the firefighters and the paramedics is very emotionally distressing," she said.

Gray had been in Vancouver making a delivery to a florists' supply shop as part of his business on the Sunshine Coast. The original 911 call was about an agitated man who sprayed a woman with a garden hose, the inquest has heard.

Campbell testified that the only information he received before getting to the scene with other firefighters was that there had been a "bear-spray incident."

Additional personnel from BC Emergency Health Services as well as the Independent Investigations Office and others are expected to testify later this week.

An inquest jury isn't able to make findings of legal responsibility but it may make recommendations to prevent similar deaths in the future.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published April 25, 2023.

Brenna Owen, The Canadian Press