WESTERN PRODUCER — Designing a futures contract is one thing. Getting people to use it is another.

That’s always been true and it’s going to be true about the new Chicago Canadian wheat futures contract.

“Liquidity will be the big issue,” said Errol Anderson of Pro Market, who is eager to see the new contract on the Chicago Board of Trade come to life and thrive.

“We need commercial participation.”

John Duvenaud of the Wild Oats Grain Market Advisory would also like to see the contract thrive, but doubts that it will.

“It’ll be a real commodity. It’ll be (on) a real trading platform that works. But the liquidity will not be there to make an efficient and effective market,” said Duvenaud, a long-time trader in Canadian grain futures.

The history of agricultural futures markets is littered with failed attempts to launch new contracts.

Anybody remember the Minneapolis Grain Exchange’s attempt to create a tiger shrimp contract?

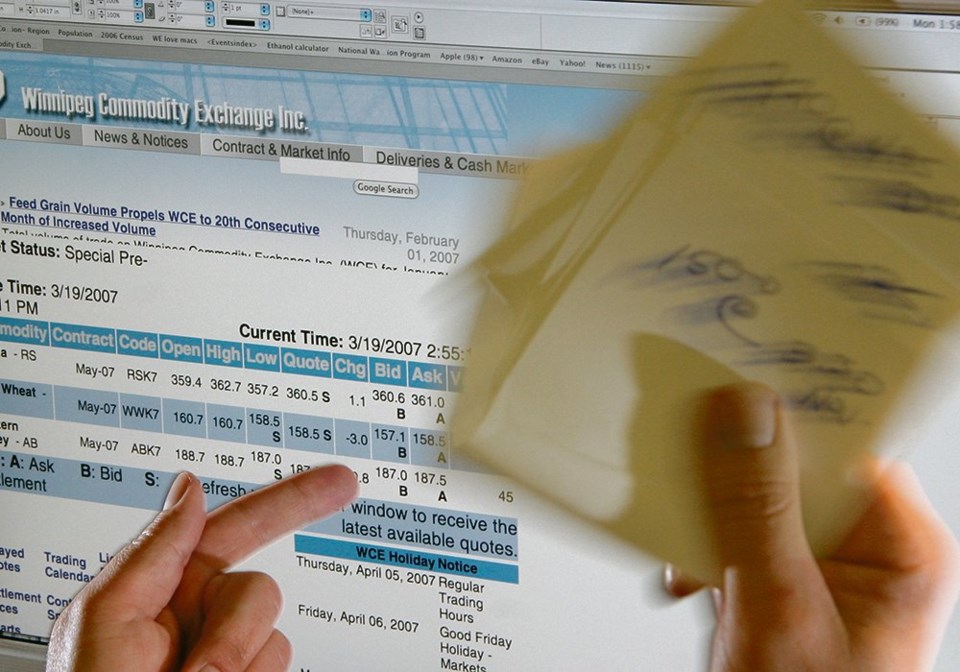

Ag futures history is also filled with the deaths of formerly used contracts that lost their users. In just a few years in the 2000s we saw feed wheat, oats, barley and flax contracts at the Winnipeg Commodity Exchange (now part of the ICE network of exchanges) shrivel and die.

It’s not due to a lack of effort. Exchanges establish committees and consult extensively with commercial users, farmers, traders and investors when they’re trying to develop a new futures contract.

Often the idea has come from commercial users or traders, who see something missing in the marketplace and say, “hey, why don’t you guys create an XYZ contract? Everybody wants one.”

Ideas are developed and circulated. Draft contracts are sent out to likely users for feedback. Scenarios get played out by people and computers. Academics are consulted. Lots of preparation takes place before any new contract is launched.

But the moment of truth comes when the contract goes live and people are able to use it. Does anybody step in to start taking positions? Do enough people establish positions and trade the contract to give it the liquidity it needs to feel safe to position holders?

That’s when the commitment of traders, the grain trade and farmers gets tested, and often it isn’t there. If you can’t get out of a contract, nobody will want to get into it in the first place.

This contract won’t likely work too well as a hedging tool for prairie farmers because it is priced out of Vancouver. It’s not attempting to anticipate elevator prices directly. Due to the uniquely tortuous logistics that connect the Prairies to Vancouver, there can be significant spreads in the value of crops between the land on the east of the Rockies and port.

For wheat spread traders it should invite another enticing play, but there is already a hard red spring wheat contract trading in Minneapolis, so it’ll probably need to prove itself to provide a different wheat value than one could get from using Minneapolis. The Chicago Black Sea wheat futures contract hasn’t exactly been a booming success so far since being launched in 2017.

Will it work well as a reflection of world wheat prices? Its ability to do so is complicated by those tortuous rail lines that occasionally, like this past winter, cut off the Prairies from the West Coast.

None of this means the contract can’t work. The CME Group, which owns the CBOT, wouldn’t be launching it if it didn’t think there was a good chance of it thriving. It’s a very smart and successful organization.

And some big players could decide they really want it and take steps to make sure it does. Duvenaud remembers how grain industry giant George Richardson ensured that Winnipeg canola futures took life by instructing his company’s traders to take every fairly priced bid and ask.

“It takes somebody like that to get it started,” said Duvenaud.

“That contract has never looked back.”

It’ll be great if the Canadian wheat futures contract works out as Chicago hopes. Any new hedging and price transparency tool would be a welcome addition to Canada’s farmers and grain industry.

But it’s like launching a ship into perilous waters that have seen many other vessels founder and sink. We can only hope this one is piloted well and makes it into safe seas.