WESTERN PRODUCER — Expert opinions about the application and effectiveness of variable rate systems across the Prairies are, well, variable

As prairie soil scientists delve more deeply into the muddy picture of VRF payback, they seem to be in general agreement that variable rate fertilizer works better in some situations than others.

The conclusions drawn by the Alberta Agriculture VRF payback study told an interesting story.

The Western Producer conducted interviews with four soil scientists associated with the research. All four are now retired.

- Alberta Agriculture’s Ross McKenzie initiated the study in 2010.

- Alberta Agriculture’s Doon Pauly took over the study when McKenzie retired and completed it in 2014.

- Ray Dowbenko, former senior agronomist at Agrium, provided financial and personal support and reviewed the study.

- Don Flaten, soil scientist at University of Manitoba, reviewed the study.

McKenzie: “We wanted sites that were quite variable in topography. On a quarter section, the plots were a half-mile long and two metres wide across a range of topographic conditions.”

“We typically had 16 different benchmark positions at each study site. Each benchmark was sampled and tested in detail for nitrogen, phosphorous, potassium, sulfur, boron, copper, iron, zinc, pH, EC and organic matter. And we monitored soil moisture throughout the season with a neutron probe.

“For example, with nitrogen we had rates from zero up to 150 pounds per acre and each treatment ran the full half mile. Then we harvested 16 different benchmark positions. This is a very close resemblance to what happens in a farmer’s field. Our small plot combine is very precise. The yield data we collected was much more accurate than a yield monitor on a combine.”

Was the trial big enough to form valid conclusions? McKenzie says the trial design was certainly adequate to draw valid conclusions. But it cannot apply to all farmers in all soil and agroecological zones across the Prairies. The focus was on southern Alberta, which is where four of the five sites were located for three years. Four of the five sites were in brown and dark brown zones, with one in the Black zone.

“What’s important is that the slope of N response curves were very similar with each topographic position. So, the crop yield at the same N treatments were different but the optimum N rate was usually the same for each benchmark slope position. This was similar at most sites and is critically important.”

He says VRF did not pay for itself in the 16-site-year trial. However, in a field with greater topography and in certain years, he says variable rate would likely pay for itself.

“If you go to your precision agronomist, he might tell you that variable rate will pay on every one of your fields, but in fact it may only be 25 to 50 percent of your fields. The more variable your topography, the more variable your soils and the more likely you are to get a benefit.”

McKenzie says agronomists and farmers across the three prairie provinces are disadvantaged because there is very little soil test calibration research anymore across the three provinces.

There’s very little soil test calibration research with crop response that occurs anymore across the three prairie provinces. In Alberta, there is no co-ordinated soil test-fertilizer calibration, following Alberta Agriculture layoffs. As a result, the information available to soil testing labs, agronomists and farmers is becoming older.

The data base and thus the fertility recommendations that had been developed have been gradually becoming more obsolete by the year. There’s no choice but to base recommendations on old data.

He says updating that data should be more than a once-in-a-lifetime project as it is now, or even a once-in-a-decade project. It should be an annual on-going task for as long as agriculture exists. Using the right test for the right soil is also an issue.

“Due to variable pH in fields with variable topography and soils, it’s critically important to use the Modified Kelowna soil test P method in Alberta and Saskatchewan, which is recommended in both provinces. Many variable rate companies don’t do this. Instead, they use the old Bray and Olsen method.”

McKenzie says the Prairies have never been calibrated with the Bray method, so why use it? The Olsen method was designed for high pH soils but works poorly in soils with lower soil pH. In the VRF study, he noted that soil pH could vary from 5.2 to 7.8 on a quarter section, so using the modified Kelowna method, which is not affected by soil pH, is very important.

“Most precision agronomists who make soil/fertilizer prescription maps are not well trained in soil classification and mapping. That’s a huge deficiency.

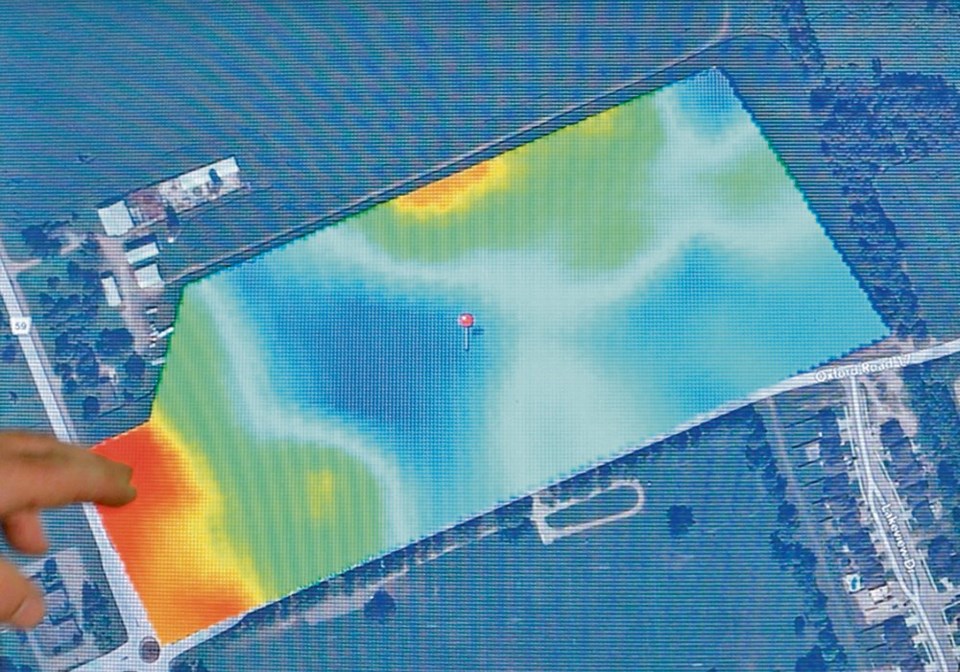

“If a farmer asked three different precision ag companies to develop soil/crop fertilizer management zones for the same field, odds are a farmer would get three different maps. Plus, the farmer would see considerable variation in the fertilizer recommendations from each firm. That’s a huge concern, but nobody will touch this subject.”

Pauly: “We had adequate rainfall those years, so that may have wiped out any measurable differences between VRF and standard rate,” recalls Pauly, adding that if you can accurately measure soil differences, then logically you should have a response to variable fertility. He says water can negate positive effects of VRF.

“But we had too much good moisture. I think when you have too much good moisture, that wipes out the potential benefit of variable rate fertility. You would assume that with more moisture, you need more fertility.

“What happens is the good moisture causes more mineralization. You have to realize there are other sources of fertility beyond what you add as fertilizer. Water triggers mineralization, but you can’t variable rate water. It’s just one of the reasons I’m not a big fan of variable rate fertility.”

Dowbenko: “We were supportive (of the trial) as a company, and myself personally, because we all wanted to know how variable rate worked in low-slope, mid-slope and hilltops. How do these positions and textural changes, organic matter and other factors respond to VRF,” says Dowbenko. “And does it pay?

“In the past few months there’s been a lot of articles in farm publications. Does it pay or doesn’t it pay? There’s been bickering and fighting on both sides.

“I haven’t followed the naysayers in the debate very closely, other than the fact they’re concerned about expensive equipment. I have heard from a number of people I trust who’ve tried VRF. They say it earns them $1.25 per acre and it’s not worth the headache so they dropped it.”

Dowbenko says that at today’s fertilizer prices, any method you can find to judiciously use those inputs should be considered. For producers who want to play the carbon sequestering card, it has to be smarter putting nutrient where it’s needed.

“I’m supportive of variable rate, but it does become a situationally specific decision. If I have tabletop flat ground, I might say it’s all looks the same. Meanwhile, other people will say that no, it’s not all the same even though it all looks the same. How do you decide?”

Flaten: “It takes a good variable rate program to be better than no variable rate program.”

That’s Flaten’s opinion of VFR programs that demand a lot of time and other resources. And in the end, he says, good moisture will give you a better yield, but it messes up all your fine VRF work.

“One of the positive things we’re finally seeing in the newer programs is that they take into account the availability of water and landscape analysis.

“These may be very significant as we move further into climate change. Most climate change models point us toward highly variable weather and climate. They say we’ll have record draught one year followed by a very wet spring the next year. These are the things we’ll have to learn to cope with. Variable rate may help us cope,” said Flaten.