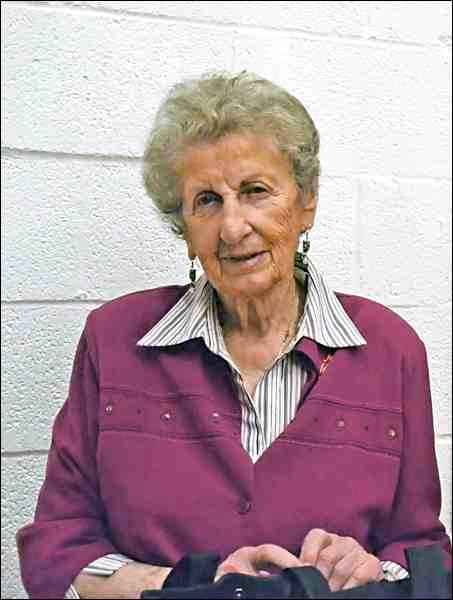

Although she's not a rock star, a thundering orator nor a "pump 'em up" motivational speaker, Eva Olsson, a small, elderly woman with a quiet, unassuming manner held some 400 teens spellbound for over an hour and brought them to their feet in a prolonged, emotional standing ovation after she had finished speaking.

Students from McLurg High School in Wilkie and Unity Composite High School, along with teachers from both schools, school community council members and others, filled the UCHS gym the afternoon of May 15. Olsson, a Holocaust survivor, was to tell her story.

In marked contrast to the hubbub of chatter, laughing and squealing of students prior to the presentation, the room was completely silent once Olsson started talking about the things that happened to her and her family during the Second World War. Black and white Holocaust photos on the large on-stage screen at the front of the room can be found in textbooks and documentaries, but were given new meaning as Olsson related her personal experiences.

The current generation of students are the last generation able to hear a first-hand account of the Holocaust, the last generation who will have a personal memory of a face and voice to put with the photographs and facts in the history books.

Using familiar language for today's students, Olsson introduced her talk by telling the audience she was going to talk about bullies, bystanders and the power of hate. But first, she reminded everyone not every Nazi was a German and not every German was a Nazi.

"Hate" was a word she taught her son and her grandchildren not to use. She asked students and adults to raise their hand if they use the word "hate." The UCHS gym was a forest of arms, hands up in the air. "Hate is a killer I don't use the word 'hate,'" she said.

She reminded everyone this is Canada. Canada is supposed to be about acceptance; that's why people came here. "When you bully others, you are being disrespectful to the country of Canada."

Olsson, now 89, has lived in Canada for 63 years and her son and three grandchildren are all Canadians. "They don't tell people they show people they're Canadians by the way they behave and the way they treat others."

Olsson asked why we're "so eager to label people?" Sometimes, she said, when a bully is asked "why," the answer is because they get a "kick" out of it. But, "kicks don't last, only the pain lasts."

Bringing the conversation around to the past, Olsson said there were 300 Nazi bullies in Germany in 1928. By 1933, there were 300,000. Bystanders were not innocent. "Remaining silent gives power to the bully," she said.

One and a half million children - children, 15 and under - were murdered. "Five of those children were my nieces, ages three, two, one, six months and two months. I'm here to speak for them and all the other children whose voices were silenced by hate."

Olsson's parents were poor Hungarian Jews. The family lived in two rooms with no electricity and no running water. In 1934, there were 19 people living in those two rooms as the whole family had come "together in fear."

May 15, 1944 - 70 years ago to the day Olsson was in Unity speaking to high school students - the entire family was ordered to pack their bags. They were to go to Germany to work in a brick factory. They had two hours to get ready and then were marched to the railway station, seven kilometres away.

At the railway station, they were ordered into boxcars, 100 to 110 people per car. It was standing room only. There were two buckets in each boxcar - one for drinking water and one for use as a toilet. There was little air and the older people died, "70 years ago today." People were praying. People were crying.

Olsson saw her mother crying, squatting down, "hugging my sister and her three little girls." Her mother said she was crying for the little ones; "I'm 49 years old. I have lived."

They were in the boxcar for four days and four nights - standing day and night. More elderly died. Children cried because their mothers couldn't feed them.

They arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau, which, although they didn't know, was "not a brick factory. It was a killing factory."

They had to line up. The "Angel of Death," Dr. Josef Mengele looked at them, each in turn. Men and women were in two separate lines. Mengele didn't speak; he simply waved his wand to the right or the left and that was where you went.

Olsson was holding one of her little nieces by the hand. More than once, a prisoner came up to Olsson to tell her, "Give the child to an older woman." Finally, she let her mother take the little girl's hand - a simple act that meant the difference between life and death for herself.

Olsson and her younger sister went to the right. Her mother, and any woman with a child, went to the left. "I turned to (look) ... I didn't see my Mom. It was so quick, with no chance to say goodbye or I love you or I'm sorry for disobeying you."

Why do we disobey our parents, Olsson asked the students, answering her own question by saying "We want to prove Mom wrong. But it doesn't matter who is right or who is wrong. What matters is love." It is OK to disagree; disagreement doesn't need to create hate.

The older men and women, the children, anyone who seemed to be in poor health - they all went to the gas chamber. It took 20 minutes for them to die, and the children would always be found at the bottom afterwards, crushed by the weight of the bodies above them. The hair was cut off the bodies. Tons of human hair was used to make felt for horse blankets and socks for soldiers.

Anyone not sent to the gas chambers was ordered to strip. If you appeared healthy, you were sent to the bathhouse and then the barracks. You didn't get your clothes back, just rough prisoner garb. In camp, the daily ration was one piece of bread - "70 per cent sawdust dirty water soup," made from unwashed potato peelings, and coffee.

The terror and bullying were not limited to Germany, Austria and Hungary.

In Romania, Jews were also loaded into boxcars. But these "death trains" didn't have a destination; they simply travelled up and down the track until everyone was dead.

In the Ukraine, Ukrainian police shot Jewish women. Over 2,000 Jewish women were shot in two days, one by one by one. If a woman was holding a baby, the instructions were to shoot the baby first because chances were the bullet would go through the baby and kill the mother as well - two deaths for one bullet.

But not everyone was a bully and not everyone was a bystander. Bulgaria was occupied but the Bulgarians didn't allow the trains to leave their country. Denmark was occupied and "7,200 Danish Jews were smuggled to Sweden in fishing boats."

Someone's origin doesn't matter, Olsson said. "We're still part of the same race, the human race. Attitude is what makes us different." Do we respect others, value home life, have compassion?

Olsson's mother and the children were the first victims of her family, but not the last. Her father was 48 years old and in good health. He was sent to a slave labour camp and died of starvation, six and a half months later.

Eleven million people died, not because of old age or illness or accident, but because of hate; "11 million voices were silenced by hate and that is not acceptable."

Olsson urged students, before saying "I hate you," to stop and count to 10. "Think of the victims your own age who died because of hate. Hate does not help us develop a good character."

Olsson and her sister were sent to Dusseldorf where they were dumped in a field. There were no buildings. They slept on the ground under pup tents which did not keep out the rain. Each morning, they had to be up at 4:30 to unload bricks at the river. Five weeks later, along with some others, Olsson and her sister went to an ammunition factory, which was an improvement. "We were fed there. Not by the Nazis, by the factory owners."

In October, 1944, they were marched back to camp, to Bergen-Belsen, to smoke and rubbish. The camp had been bombed. In some bombed camps, the prisoners were shot. "Here they found us a hole in the ground, straw on a dirt floor, underneath the kitchen."

The straw started to rot. There was no water, no toilet paper. Winter came and all they had to wear to march to work and back were wooden clogs - no socks, no underwear. "We were dirty and we were wet."

Dysentery set in. The prisoners still slept on the floor, a floor covered with diarrhea and lice. The ground outside looked the same as the floor inside and 104,000 people died. "There was not enough food or water to sustain life."

Fever set in. With no water and no mother to hold a soothing wet cloth on her forehead, Olsson peed on a rag. She saw other young women drinking their own urine because they were so thirsty.

Six days before they were liberated, the Gestapo took away even the dirty water soup. Five hundred prisoners died every day. Olsson had her younger sister beside her and thought, "I cannot die here; who is going to look after her?"

In April, 1945, the Gestapo knew they were losing the war. They planned to abandon the camp at Bergen-Belsen and scheduled the shooting of all prisoners for April 15 at 3 p.m. At 11 a.m., Olsson and the others were liberated by Canadian and British soldiers who had come from Holland.

"I was very sick but I knew I was free." Fourteen thousand died after being liberated. "The doctors couldn't help them but they died free."

"I was free of being killed but never from the memories," Olsson said, saying Neo-Nazis are still marching in the capital of Hungary. In the Ukraine, Jews are once again, "right now," being asked to register.

"I can't change the past and the future depends on you Don't be scared of 'different.' What we need to fear is indifference."

After the war, Olsson went to Sweden where she met her husband. They moved to Canada where he was hit by a drunk driver at the age of 35, eventually succumbing to his injuries.

But he gave Olsson a gift "and that's what I give to you - unconditional love and acceptance of another human being - I give it to you on condition you pass it on to other children."

Olsson concluded her powerful presentation by saying, "For 50 years, I was silent but silence doesn't heal. I want to thank you for allowing me to keep my family's spirit alive."

For those interested in learning more about Eva Olsson, her website is http://www.evaolsson.ca. She has written several books about her experiences and about the need to fully accept other human beings, whatever their race or religion. Her books can be purchased through the website.