No grave, ruined building foundation or discarded tin can uncovered on a dig site tells a story on its own. Without someone sifting through records, remembrances and, perhaps, tall tales to relate the archeology to a story, the artifacts are silent.

A former North Battleford resident, Robert Clipperton, has sifted through newspaper excerpts, archival correspondence and other documents relating to an event known as the Cypress Hills Massacre to create a book that helps interpret archeological discoveries made during two investigations of the site.

He calls himself the "editor" of the book, because only a few pages are actually authored by him. But the contents resulting from his "digging behind the dig" represent more than a pulling together of easily available existing material.

Perhaps "editor" is the appropriate term, however, as Clipperton posits no authorial hypothesis aspiring to become a definitive version of history.

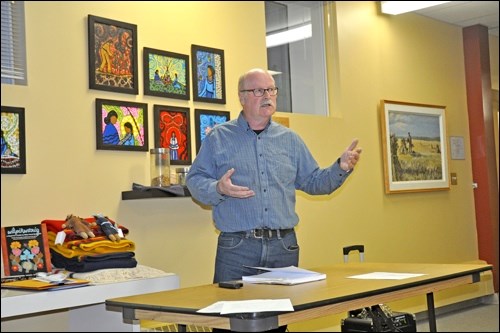

"I keep my opinion out of it," he told a group gathered at the Allen Sapp Gallery in North Battleford for the annual meeting of the North West Archaeological Society recently.

"There's still a lot we don't know," said Clipperton, a past president of the Saskatchewan Archeological Society.

While he spent the better part of two winters researching and assembling material for the book, produced by the Saskatchewan Archeological Society, he suspects there is more material to be found – if one had unlimited time and could get past the barrier of unhelpful, uninterested or just plain overworked individuals who have custody of such records. Of course, some key records may have been lost forever in the 1897 fire in the West Block of the Parliament buildings.

Clipperton, who taught school in the Battlefords area until he moved to Saskatoon to take on social work, is now retired. It was during his time as a teacher at Cando, which serves a First Nation population, that he became interested in First Nation issues and history.

The first part of the book Cypress Hills Massacre centres on the 1873 killing of a number of Assiniboine (Nakoda) Indians by a group of Montana wolfers in southern Saskatchewan, still part of the North-West Territories at that time, June 1, 1873. Two nearby trading posts, representing American interests, factor into the story as well.

While the exact course of events, which reportedly arose out of the American wolfers seeking to recover horses that had been stolen from them, remains a mystery, the Cypress Hill Massacre is recognized as one of the most violent episodes in the Canadian west. It is also generally credited as the catalyst to bringing the newly formed North-West Mounted Police to the area.

Clipperton has compiled excerpts from contemporary Montana and Canadian newspapers, archival correspondence and other documents, some previously published, some not, that refer to the event. Information has been gleaned from reports from witnesses, the wolfers, other people in the area, survivors and their descendants, said Clipperton. He has included information from police historian John Peter Turner, historical sleuths George Shepherd and Zachary Hamilton and Assiniboine chief Dan Kennedy.

As can be expected, he pointed out, there's no neat lineup of information. Some accounts are wildly different, especially between American and Canadian newspaper accounts, as the attitudes of the day colour the recounting of history, even to the number of people involved.

The American attitude toward First Nation people at the time was they were a pest to be rid of, while the Canadian stand was that Americans had murdered subjects of the British queen, said Clipperton.

Putting it in the context of the whiskey trade, said Clipperton, by 1874, there were probably 50 trading posts in the area, and there had been reports of other atrocities. So entered the NWMP. The area needed policing.

As part of the overall picture, Clipperton delves into the aftermath of the Cypress Hills Massacre, from assistant commissioner of the NWMP James Macleod's trip to Helena, Mont. in an unsuccessful effort to have the wolfers tried and then extradited to Canada for punishment, to the acquittal of three of them who were subsequently found and arrested in Canada.

Interestingly, he said, the newspapers of the time were the record of court proceedings, as there was no such recording done by the court itself. Macleod, while in Montana, knowing coverage would be slanted one way or another, engaged a person to record the trial for the NWMP. It is likely, Clipperton has discovered, this is one of the records lost in the 1897 fire in Ottawa.

Clipperton says, "Searching through written records is kind of like archeology."

Like an archeologist, the researcher must stay objective and let the evidence speak for itself.

But Clipperton has also been involved in the physical search for answers to the mysteries of the Cypress Hills Massacre, on site as a volunteer during digs there.

The book contains information from archaeological work that took place in 1972 at Solomon's Post, and a full report on the work at nearby Farwell's post from 2008 to 2010, the findings of archeologist Donalee Deck. The area is now designated a national historic site.

For the Northwest Archeological Society members, Clipperton highlighted some of the correlations between the research and archeological findings that helped confirm the correct site had been found. One was the description of the grave of one of the wolfers who had been killed during the conflict.

Throughout Clipperton's findings, there are jumping off points for many more stories, but, as he said, if he only had unlimited time.