Editor's Note: This feature was originally published in the Battlefords News-Optimist Jan. 26, 2005.

When you ask Herb Sparrow, the recently retired senator of 37 years from North Battleford, if he's a hard-nosed politician, his response is quick and definitive.

"You bet!"

Over the course of an in-depth interview with the News-Optimist looking back at his nearly four decades in Canada's chamber of sober second thought, Sparrow often reflects on the battles that did not necessarily make him popular, but allowed himself to look in the mirror at night.

Early Years

Being sworn in as a senator on Feb. 12, 1968, Sparrow became at the time the youngest senator to sit in the chamber. He was 38 years old.

Having grown up on a farm in the Vanscoy area, Sparrow attended Bedford Road Collegiate in Saskatoon. Out of high school he worked for the Bank of Commerce in North Battleford as a teller, then progressed through positions with Beaver Lumber in Kerrobert and then selling cars back in North Battleford.

In 1951 he married Lois Perkins of North Battleford. The two, now married for over half a century, had six children - Kenneth, Joanne, Bryan, Lauren, Robert and Ronald.

By 1954, Sparrow saw an opportunity to get into the food business, becoming one of the pioneers in the fast food revolution that would sweep North America in the coming years. His Ranch House restaurant on North Battleford's 100th Street sold hamburgers and southern fried chicken. In 1958, he became the third Kentucky Fried Chicken franchisee in Canada and the 11th in North America.

The current KFC, having undergone a recent renovation, is on the same site of the original Ranch House. Sparrow also set up a franchise in Meadow Lake, and has recently sold off several locations in the United States.

Maintaining a restaurant for over 50 years is a testament to "good food, good service, good management and a good product," Sparrow said.

Col. Harland Sanders ("Col. Sanders") was a frequent visitor - coming to North Battleford 40 or 50 times, especially in the early years. Sanders became involved with one of Sparrow's many charitable ventures, the building of the School for the Retarded (later known as Centennial School), often making donations to the project Sparrow headed.

By 1961, the restaurant was making enough money that Sparrow was able to give up car sales. But in 1964, he felt the bug to return to the land, and started farming and ranching just north of the city. He still farms, but thankfully left the cattle business just before the mad cow crisis hit.

Entry to Politics

Sparrow was first elected to city council in 1955 at the age of 25, and sat on council until 1964. By the mid-'60s he was heavily involved with the Liberal party, having risen to the position of provincial party president. Unfortunately, he had little luck at the polls, being defeated in both the 1964 and 1967 provincial elections, elections that the Liberals carried provincially.

During the last year of his administration, Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson appointed Sparrow to the red chamber. "You have to be wealthy, good looking, well educated and bilingual, but they couldn't find anybody like that, so they appointed me," Sparrow said in a well-rehearsed line.

A wide variety of people are typically chosen for the senate, he said - farmers, trades people, university types - each bringing a viewpoint to a very broadly based chamber of sober second thought.

His own appointment probably shocked many at the time, Sparrow said. That appointment took place rather quickly. He received the phone call on a Friday, and the following Tuesday, he was being sworn in on Parliament Hill. While he travelled alone to Ottawa, Sparrow was happy to be surprised by the presence of his five brothers in the gallery.

Even though he spent nearly four decades in Ottawa, Sparrow never truly lived in Ottawa - staying in either an apartment or hotel room. He never even kept a car there. "We made the decision not to move to Ottawa," he noted. That decision proved important over the years. "It's surprising how rapidly you lose contact with your riding, even in a few months," he said of politicians who decide to make Ottawa their home base.

But being away for so long takes its toll, especially on family life. He literally criss-crossed the country many times each year, especially when doing committee work. His career saw a full five years, 365 days per year, were spent in the air and in airports, eight and a half hours each time back and forth to Ottawa.

"I would never recommend it for anyone else. You're away too much. You have to have a good wife at home looking after those kids, which I was fortunate enough to have."

Big Issues, Big Battles

Some of the big issues Sparrow tackled included poverty and soil conservation. Very early in his career, the North Battleford senator was part of a committee tackling poverty in Canada. Indeed, that committee went so far as to formally define what the poverty line is in Canada. The intrepid young senator in 1969 wanted to see just to see what poverty truly meant. "I spent a full week on skid row in Vancouver, living with people there," he recalls, saying he spent 24 hours a day lving that way in 1969.

That led to a long-held belief that Canada needs a guaranteed annual income for all people. While that is somewhat accomplished by varying programs like welfare, child benefits and other initiatives, he'd like to see a guarantee solidified.

Soil Conservation

During the 1980s Sparrow concentrated his efforts on a senate committee report on soil conservation. Soil at Risk became a seminal work, with such impact as to literally change the way people farm on the prairies and around the world. There used to be 45 per cent of crop land in summer fallow each year, now that number is five per cent, he notes.

"The issue was so serious, I would take ten years of my life to do this," he recalls.

The report, which at 50,000 copies has had a print run ten times greater than the threshold for a Canadian bestseller, is still being requested. Recently, another 400 were sent to Australia.

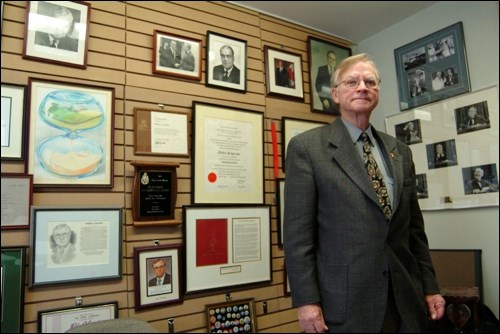

His North Battleford office, located close by to KFC, is festooned with accolades for that work. The short list of the honours include an honorary doctorate from McGill University, a medal from the United Nations for conservation, citations for various halls of fame and the H.R. MacMillan Laureate. That final honour, given to Sparrow in 1989, is awarded to the Canadian who has given the greatest contribution to Canadian agriculture in the past five years. It is awarded only twice a decade.

Butting heads

For 10 years, Sparrow was the deputy chair of the senate finance committee, going over the federal budget with a fine toothed comb. He speaks of arguments with Prime Minister Trudeau over economic policies - policies that Trudeau and economists of the time felt were right for the country, but time eventually proved wrong. In particular, Sparrow said government spending should never exceed growth in gross domestic product. Yet through the Trudeau and Mulroney eras, deficits ballooned to astounding proportions.

"Trudeau's economics were essentially flawed," he said.

It took Paul Martin as finance minister to finally put a stop to that way of thinking, he said.

One key fiscal policy did not bode well for the country, Sparrow added.

"The GST was, still in my mind, a mistake. It's a direct tax on the poor people."

The GST came in at a time when the economy was in a downslide, and took a seven per cent slice. "It almost ruined Saskatchewan, whether anyone wants to admit it or not," he asserted.

A better choice would have been to derive the revenue from income tax, in his opinion.

"Chretien promised me, in front of caucus, he would cancel the GST," Sparrow recounts. That promise was not followed through, and for that, "I never forgave him," Sparrow said.

The long time senator developed an independent streak, one that is rare in Canadian politics and rarer still in governing parties. Two points in particular stood out for Sparrow.

The Charlottetown Accord was all the rage in political circles in 1992, thought to sweep the nation with support. But Sparrow felt it had fundamental flaws, including guaranteeing Quebec 25 per cent of the seats in the House of Commons in perpetuity, and giving Ontario and Quebec control of half the senate. "It would not sell in my province," he felt, and with Senator Ed Lawson of British Columbia, became the only two senators to vote against the Charlottetown Accord.

"Do you think I was popular?" he asked.

But history proved him right, and in the end, the country overwhelmingly defeated Charlottetown.

A few years later, the newly elected Chretien Liberal government moved to tear up a deal to sell Toronto's Pearson International Airport to private hands. Sparrow took umbrage with the bill that would remove the investor's right to sue the government, and was the deciding vote against his own government. Again, he asks, "Do you think I was popular?"

"They knew I was my own man," he said of those on Parliament Hill. But when asked how many parliamentarians out there could truly say the same of themselves, the senator paused. A very long pause. Finally he said, "Few. Few. I want to qualify that. There's quite a few that would take strong stands in committee," he said, adding that many battles are fought in caucus as well. But when the final vote comes, most vote the party line.

The work leading up to those votes - the "sober, second thought" of the Senate - is very important, he said. Many bills that originate in the House of Commons need some serious work before becoming law. As many as a third are amended by the senate. One transport bill, he noted, took several rounds, but in the end the Commons accepted all 140 Senate amendments made to it.

Calls to reform or abolish the senate miss the point, he said. Both would concentrate more power in the hands of the Prime Minister's Office (PMO). An elected senate would add another 106 people under the heal of the prime minister or leader of the opposition. Abolish the senate, and "you leave the PMO in a total dictatorship."

For his final few years in the red chamber, Sparrow was considered the 'dean' of the senate, being the longest serving current member.

On the occasion of his 35th anniversary in the senate, Conservative Senator David Tkachuk said, "Honourable senators, I would like to say a few words about Senator Sparrow. More Liberals should be like Senator Sparrow, because he agrees with many of the things we on this side of the house say. When Liberals say 'independence of thought,'' they really mean that what they say is right and that what we say is partisan.

"Senator Sparrow stands as a lie to that statement. He actually is an independent thinker. He is a joy to work with and a fun companion on trips back to Saskatchewan. He enlightens us with all kinds of stories about the Liberal Party from years ago - although nothing from the present. We exchange political stories and we have become good friends."

Some of his final words in the senate showcased Sparrow's trademark humour.

"I have told some of you this story before. I was introduced at a meeting as Senator Swallow from Alberta who was in the oil business and had made $250,000 the previous year. When I rose to speak, I had to correct that. I said, 'I am not Senator Swallow; I am Senator Sparrow. I am not from Alberta; I am from Saskatchewan. I am not in the oil business; I am a farmer. I did not make $250,000 last year; I lost $250,000.'"

After such a lengthy career, does he have any regrets?

"No, I have no regrets. I believe I filled the job I was meant to do. I feel I was able to look myself in the mirror