To hear local author Wayne Brown tell it, the North West Resistance is a tale of larger-than-life characters, calamity, disorganization and hardship.

The people involved in the North West Resistance make for interesting reading. Brown says many people were true to their surnames.

For example, General T.B. Strange, commander of the Alberta Field Force, truly was strange. "He walked so erectly that people thought he was going to fall over backwards," says Brown.

Steele "was exactly that," says Brown, referring to Sam Steele, a North West Mounted Policeman and leader of Steele's Scouts. Steele trusted William Fury above all others, even giving him authority over higher-ranking officers. Fury was "just a ball of fire," says Brown.

Cree leaders like Big Bear faced leadership challenges at this time, says Brown. Their people suffered from hunger and disease, and councils were held to find ways of dealing with this hardship. However, the Woodland and Plains Cree bands were different culturally. Brown says this kept them from achieving consensus, which was needed before they could enact a decision. When the Cree learned a resistance had begun, Wandering Spirit and his warriors reacted. In the end, nine people were murdered at Frog Lake, and the Cree were embroiled in the resistance.

At Fort Pitt, William McLean, a Hudson's Bay fur trader, wisely helped negotiate the capitulation of the fort, says Brown. By this time the police, under the command of Francis Dickens (a descendant of writer Charles Dickens) had fled. McLean's three daughters were comfortable living in the wild west. They spoke Cree and Saulteaux and were proficient with firearms, says Brown. The McLean family was friends with Sitting Bull, and he admired one of the girls so much he traded two horses to purchase a necklace for her, says Brown.

The McLean girls showed tremendous grit during the resistance. While William was at the Cree camp negotiating the surrender of Fort Pitt, three scouts tried to gallop to the fort, and the Cree believed they were under attack. One scout was killed, and another wounded. The McLean girls provided cover fire as the wounded man was brought back to the fort. Then, concerned for the safety of their father, Amelia and Katherine walked to the Cree camp, unescorted. When the Cree braves asked them whether they were afraid, the girls replied they had no reason to be afraid. The McLean family, along with the rest of the Fort Pitt residents, then travelled as hostages with the Cree.

After the resistance was over, one newspaper article quoted Amelia as saying, though her time with the Cree was difficult, she now looked back on most of it with enjoyment. The hostages, along with the Cree warriors and non-combatants (mainly women and children) faced hunger and long, difficult treks through the bush. Amelia was 17 at this time.

General Strange and his Alberta Field Force arrived at Fort Pitt on May 26, 1885. They were generally undersupplied and a little disorganized, which led to problems.

Shortly after arriving at Fort Pitt, Sam Steele was sent out with his men to look for the Cree. The Scouts were near Pipestone Creek one evening when they ran into Cree warriors. "The Cree warriors were heading to Fort Pitt to raid horses. They ran into each other in the dark," says Brown.

A gunfight broke out for about 10 minutes and Memmnook, a Cree warrior, was killed.

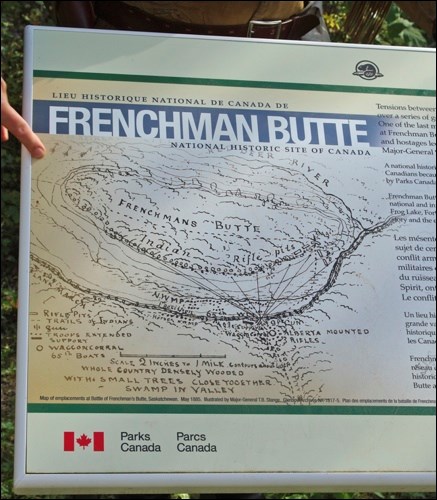

At this point, Strange and the Alberta Field Force left Fort Pitt in a hurry, hot on the trail of the Cree. They didn't bring supplies, and the troops responsible for firing the field gun were off on another scouting mission. When they got to Frenchman Butte, they were ill-prepared for the ensuing battle with the Cree.

The Cree had set a trap, explains Brown. They had set up flagging to draw Strange's troops in, and dug and camouflaged rifle pits. Strange thought the flagging was suspicious, but he was still forced to fight from a somewhat difficult position. He soon learned his men would not be able to cross the gully to charge the rifle pits on the other side.

"When they got to the flat, they saw that it was a swamp, and no one's going anywhere," says Brown.

The flagging was not Wandering Spirit's only trick. When he saw Steele and his men moving, Wandering Spirit grabbed a few men, and shadowed Steele from the Cree side of the gully. The Cree ran along the ridge, then popped up and took a few shots at Steele and his men before ducking and running again. This fooled Steele into thinking that the Cree reinforcements were much stronger than they were.

As the battle wore on, Strange started to face rebellion from his officers, was concerned about the lack of supplies, and was in danger of being surrounded by the Cree. He ordered a retreat, but when he got to the river, the men who were supposed to watch the boats had already fled with them, Brown says. In the end, Strange and his men had to march back to Fort Pitt.

Steele's Scouts were sent after the Cree, to attempt to free the hostages. The Scouts followed the Cree all the way to Loon Lake, once again without food, blankets or adequate fire power. Steele expected General Middleton to catch up with him, bringing supplies. However, by the time they reached Steele Narrows, they were down to 10 rounds of ammo.

"The Cree were down to shooting rocks," says Brown. After skirmishing with the Cree, Steele pulled his men out.

Wayne Brown's book, Steele's Scouts: Samuel Benfield Steele and the Northwest Rebellion, can be purchased online at www.heritagehouse.ca.

Visit our photo gallery under the community tab for more photos.