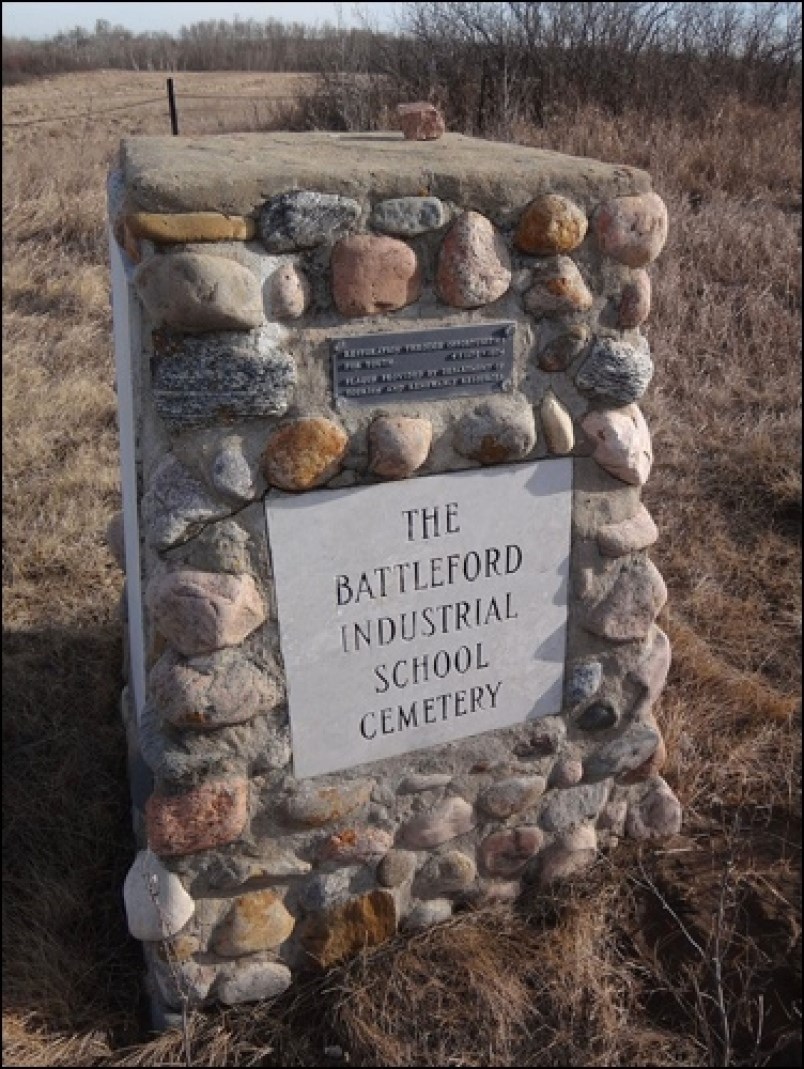

At a public meeting Monday evening, a local group reported their progress regarding historical designations of the Battleford Industrial School Cemetery.

The RM of Battle River, within which the cemetery is located, has passed a bylaw granting municipal historical designation of the site.

The next step, lawyer Ben Feist said, would be provincial designation, which the group plans to work toward in the next 30 days.

About a dozen people were at the meeting at the North Battleford Public Library, including members of the historical society.

The project, along with Feist, is led by lawyer Eleanore Sunchild, who has worked on a number of former residential school claims, and Sherron Burns, who works as a learning consultant with Living Sky School Division.

Burns got involved with the cemetery as a result of trying to do a project with high school students. The cemetery site is located on land owned by Wayne and Catherine Kopp of Stettler, Alta. Burns wanted to visit the cemetery site for educational purposes, but was refused access.

Reasons for denying access have reportedly included the presence of broken beer bottles and garbage in the area.

The cemetery is located near the former Government House. The Battleford Industrial School occupied the building, and the school was in operation from 1883 to 1914.

Feist said the school near Battleford was the first federally sponsored Department of Indian Affairs residential school in Canada.

Indian children were removed from reserves and brought to residential schools. Schools intended to assimilate children. Tuberculosis was an oft-cited occurrence, according to contemporary newspapers.

Many former students have come forward speaking out against residential schools, citing physical and sexual abuse, and trauma.

In the mid-1970s, University of Saskatchewan students and staff found 72 graves at the site as part of an excavation.

A cairn was later erected featuring names of some of those buried there.

Some of the known names can be found in northern Saskatchewan, the Meadow Lake area and nearby First Nations including Sweetgrass, Poundmaker and Mosquito. Surnames found on the cairn include Armstrong, Bird, Crookedneck, Moosomin, Peyachew and Pooyak. Albert is also engraved.

Feist explained the process of obtaining historical designations. The group looked at the title for the property the cemetery is on, and saw there were no designations registered under the title. The group went to the RM of Battle River. Councillors then communicated with the landowner. This was followed by passing a bylaw.

“Getting a municipal heritage designation means that there’s a permanent interest that’s registered on the land title,” Feist said.

The designation would legally prevent current and future landowners “from doing things like removing the cairn or removing the gravestones or plowing through the site” and turning the surrounding area into farmland.

Legally accessing the site has been a problem for the group.

The provincial Cemeteries Act states “an owner shall provide reasonable access to the public for visitation to any lot in the cemetery.”

The act defines cemetery as “any land or place that is set apart or used as a place of interment, and that is approved as a cemetery pursuant to this Act.”

Feist said the language was circular. The Battleford Industrial School Cemetery is a cemetery according to the normal meaning of the word, Feist said, but it is not a cemetery as the term is defined in the act. Thus no public access is guaranteed under the act.

The cemetery isn’t covered under the act because it was a cemetery before Saskatchewan was a province, and hasn’t been registered as such since.

A representative of the province’s Financial and Consumers Affairs Authority, which is responsible for such matters, wrote to Feist saying an “absurdity” exists in the law, and the matter would be brought up for amendment “the next time the act comes up for amendment,” according to Feist. The goal would be grandfathering historical cemeteries to allow for pubic access.

The government division sent a letter to the landowner stating its position. The landowners can legally restrict visiting hours to certain times.

At it stands, accessing the site requires permission not only from the landowners, but also the oblates, who own the land that currently allows easiest access to the site, Feist said.

Feist said representatives of the oblates they’ve talked to have been accommodating.

One representative of the oblates who was in attendance at the meeting expressed dissatisfaction with the way the group went about obtaining permission, and wanted to be asked in a more direct way.

Feist said the group would pursue federal historical designation after obtaining provincial designation.

Presenters and audience also discussed future possibilities pertaining to the site, including establishing a foundation to raise money, obtaining grant money, purchasing the land and establishing on-site interpretive information.