Amek Adler was happy in Poland with his parents, three brothers, and aging grandmother.

That was before 1939 and the Nazi invasion of Poland, before he and his family were forced to wear a yellow star for being Jewish.

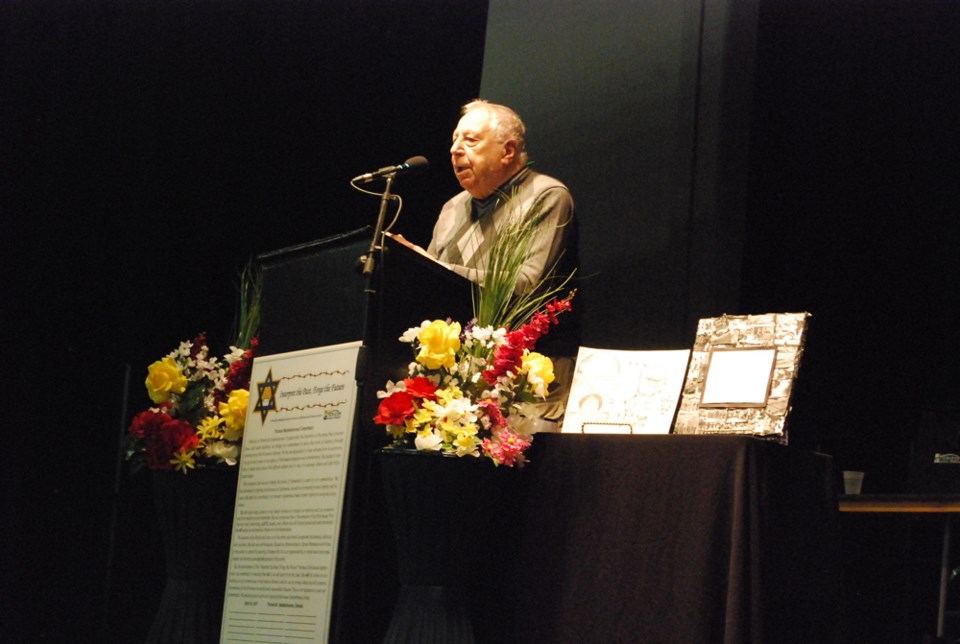

Being a survivor of the Holocaust, Adler, who lived in Toronto, was invited to tell his story at the Horizon School Division’s 3rd Annual Holocaust Symposium on April 24 in partnership with the Azrieli Foundation, an organization focused on Holocaust commemoration and education among other fields.

Unfortunately this was Adler’s last time speaking as a Holocaust survivor. He was on his way to Regina after his talk at the Symposium and sadly passed away on April 25 at Regina General Hospital.

Garinger, along with the rest of Horizon School Division, sends condolences to his family and the Azrieli Foundation. Flags will be flown at half mast at the school division office.

Adler‘s story of survival started off the symposium where 550 grade 11 students, educators, and other special guests were involved in workshops and discussions around relating to the Holocaust with the theme of “Interpret the Past, Forge the Future”.

“The opportunity to witness the direct testimony of a Holocaust survivor is an experience that people will carry with them for a lifetime,” said Kevin C. Garinger, Director of Education for Horizon School Division in a press release. “The lessons of this day, of the need for empathy, kindness, resilience and courage, are critical to a safe and caring, culturally responsive society.”

Adler made a point in mentioning during his talk that the best thing anyone can do for a Holocaust survivor was listen.

Garinger says this is the poignant message regarding all Holocaust survivors so that their stories are not lost.

“That’s something that speaks to the humanity that we all cherish and certainly appreciate about our world. In insuring that we reflect and remember those stories, it allows for us to consider a future that is much brighter.”

Adler was very open about what he witnessed as he and his family moved from ghettos to concentration camps and eventually to freedom for himself, his mother, and two of his brothers.

Surviving during that time took a few miracles, says Adler.

When things were getting too difficult in Lodz, Adler’s father secured a ride to Warsaw in the back a truck driven by a non-Jewish Polish man. The opening was closed off with furniture and they were not discovered as they drove through numerous checkpoints where the truck was examined by German soldiers.

“I consider that a miracle because if they would have caught us they would have shot us right there on the spot.”

Warsaw was not much better with construction of the Warsaw ghetto starting soon after their arrival.

The Hitler youth were frequent in the ghetto, taking pictures of the inhabitants as if they were animals in a zoo, says Adler.

An altercation with one lead to Adler’s friend being punched by one youth and Adler fighting back.

If bystanders would not have pulled him off of the youth, he probably would have killed him, he said.

“They looked for me for seven weeks. Well, they didn’t find me. That was another miracle.”

Because of being a prisoner during the Holocaust, Adler knows the screams of people as they are interrogated and shot, he knows how many people were packed into train cars, and he knows how long it took to move the bodies out of the gas chambers and into the crematoriums.

It took about 40 minutes, he said.

“It’s not a nice picture and it’s not nice to talk about,” he says, “but it’s got to come out so the world knows about it.”

Adler’s father, at 51 years old and never sick a day in his life, could not take the camps anymore, says Adler. His brother Joseph tried to escape but was shot as soon as he was caught and brought back to the camp.

By the time he escaped with two other teenagers during a prisoner transfer, he was skins and bones when he was picked up by American soldiers and taken to a hospital. It took three months before he felt human again, he says.

Along with his mother who survived by being a part of a prisoner transfer with Sweden in exchange for medical supplies, Adler was also reunited with brothers Ben and Arthur after the war was over.

In 1954, he immigrated to Canada with his wife and one year old son and he proudly calls himself Canadian.

“I think that’s the best move I’ve ever made in my life.”

Adler met fellow survivors in Canada but all they talked about he says was who had it worse during the Holocaust; whose camp was worse and who suffered more than the other person.

I did not need it, he says.

After consulting Steven Spielberg on the making of Shindler’s List, Adler says he realized then that he is doing it wrong. He has to tell his story.

He joined up with the Azrieli Foundation and have been presenting to schools and taking students on trips over seas ever since.

“I do whatever I can. It may be not much but it gives me satisfaction that I’m contributing a little bit.”