Kevin Kalthoff is in a bit of a rush.

The problem is one of time: he has six sheets of curling ice to prepare for the afternoon schedule at the Humboldt Curling Club, but less than an hour to do it. The lack of time means he has to cut back on a routine that might seem obsessive-compulsive to anyone who doesn't understand the science of making ice specifically for curling.

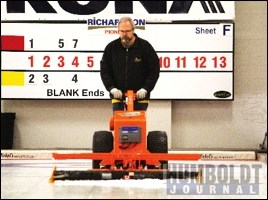

"I usually do six passes, but today I can only do four," Kalthoff says as he pushes a power scraper up and down each sheet of ice - four times each, not the usual six.

An orange machine that looks a bit like a lawnmower, the scraper has a long blade attached to the front. That blade removes the countless tiny dots of ice, called pebbles, that protrude from the surface and give the ice a feeling not unlike that of a lizard's skin. These pebbles aren't obvious unless you look closely, but they are literally what make the game go.

Even though the granite stones that curlers cast down the ice are big and weigh 40 pounds, only a very small portion -"about five-sixteenths of an inch," Kalthoff says - actually makes contact with the ice, sitting atop those tiny raised dots of ice. The pebbles act like tires on a car, allowing a big, heavy object to move along a surface with minimal friction.

Without them, according to Kalthoff, you'd be lucky to throw a stone a quarter of the way down the ice.

After scraping the ice, Kalthoff walks up and down each sheet several times while pushing a large broom, making sure no excess snow is left behind. The surface must be pristine. He even gets a little help from his wife Lois. He's been working with her since 2002, when he took early retirement from the Co-Op to take over as the club's ice technician and, more recently, as its manager.

With the ice now clean and smooth, it's now time to re-pebble the surface. To do that, Kalthoff straps on a strange looking backpack, complete with an 18-litre tank full of water heated to exactly 140 degrees Fahrenheit. At the end of a hose coming out of the tank is an oval-shaped head that looks like a beaver tail. That head is studded with exactly 74 tiny holes; when Kalthoff waves the attachment back and forth over the ice, tiny, steaming droplets of water fly out. It looks strange, almost comical, but there's a method to the madness.Once those water droplets hit the ice they freeze in between five and 10 seconds and become the new set of pebbles. It's impossible to tell the difference from afar, but the players know.

"Kevin makes excellent ice," said Ivan Buehler, who had just finished a game and was watching Kalthoff work. "You can tell the difference between good ice and bad ice very quickly."

By all accounts, Kalthoff makes great ice. As a discipline, it falls somewhere between science and art, an amalgam of intuition and consistency. There are some very specific rules, Kalthoff is quick to point out - the ice should be 23 degrees Fahrenheit; it should take 24.5 seconds for a stone to travel from the hog line to the button; there should be four feet of curl to any shot - but there's also room for a bit of experimentation.

"I'm not afraid to change things up or make mistakes," Kalthoff says as he looks over his ice from the lounge area. "That's what I tell people when I go and show them how to make ice."

Kalthoff estimates he's visited upwards of 20 communities across the province, spreading the gospel of ice making. It's obvious that he takes it seriously but also that crafting a perfect sheet of ice is a joy unto itself. Kalthoff should know what a great ice feels like, after all; he had a distinguished curling career that included three appearances at the Canadian Brier and a 2009 Senior World Championship. He hasn't curled competitively in a couple of years, choosing instead to fill his days, or at least those between October and March, taking care of the ice.

When Kalthoff arrives at the beginning of the year the future ice surface is nothing but a concrete floor. Six or seven days later, and thanks to the help of volunteers, that concrete floor has been transformed into six identical sheets of ice, each with the same distances and geometry and angles.

There are very long hours ahead once the ice goes in - anywhere between 70 and 110 per week - but, with the help of his "right-hand man" Monty Harder, Kalthoff gets it all done and has even surprised himself with how much he loves it. It doesn't hurt that he usually gets positive feedback on his ice.

"I've had lots of teams come off after they've lost a game to tell me how much they loved the ice," Kalthoff says, a smile visible under his bushy beard. "Normally you don't see that when people lose but it's happened to me a few times."

It's good that he takes compliments from others, because Kalthoff is often hard on himself.

"I'm my own worst critic," he says. "The smallest things can drive me crazy."

One of those small things is the black dividing line between the sheets. A few air bubbles had formed and in several spots the black had been replaced by white ice. It was a minor flaw, the kind that only the keenest eye could discern, but Kalthoff points to it as he went about preparing the ice for the afternoon events.

Earlier, while he was watching a tournament involving staff and councilors of various local rural municipalities, Kalthoff was asked if he was surprised by how committed he'd become to ice making.

"No, I never expected it," he said while watching stones be cast down the pleasantly pebbled surface. "I thought I'd just make ice and that would be it."

With the experience of three Briers behind him, Kalthoff knows all about what the best ice in the world is like. That's why it's hard not to believe him when he describes what he wants for the people who play on his ice.

"I want to make ice that curls like what you see on TV."