In my first year of university, I took a mandatory course on Third World issues. My second large research paper for the class dealt with malaria in Burma.

The process of writing the paper was a deeply edifying one. In writing it, I quickly realized malaria was tied up with a diverse range of issues. Not just other health issues, but everything from Burma's unenviable location in the Golden Triangle, to its ethnic history, to its history of political oppressiveness or its massive proportion of internally displaced people.

When I was finally ready to write my paper, it turned into a horrible mess. I was so overwhelmed with Burma's human rights abuses I could barely write coherently. When I wrote the paper, Burma had more child soldiers than any other country in the world, an Internet censorship program stricter than China's, was rated near the bottom of the world for press freedom and corruption. The government was corrupt enough that a number of NGOs refused to work in the country and almost all travel guide companies refused to publish Burmese guides as a form of protest. Laos, which shares a small border with Burma, receives $9 of aid per capita for every dollar Burma receives, in part because of the Burmese regime's corruption.

The process of writing the paper left me disgusted, but also invigorated. I got a perverse sort of pleasure in learning about more of Burma's shambolic faults, its woes, its sad, sad history. I subscribed, cautiously, to the mailing lists of two pro-democracy Burmese NGOs, hoping to learn if there was anything I could do for the country. When monks protested in 2007, I checked the BBC several times daily for updates on the protests.

I remained fascinated by the country long after the protests, and later had the opportunity to visit Burma as I travelled through Asia. The experience was filled with ominous undertones; I met a young man around my age who, within a week of meeting me, was arrested and sent to prison and Internet access was patchy. Every time a website didn't come up, I was left wondering whether it was because it was politically sensitive or just because the Internet infrastructure wasn't up to the task of loading it.

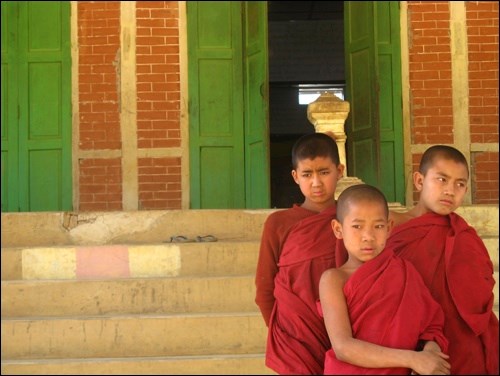

But these ominous undertones were just that - undertones. I met a large number of incredibly happy people. An American friend told me as he was biking by a small rural monastery, a monk ran out to ask if the American could help him in Photoshop. Though I had a detailed understanding of Burma's sordid history on the human rights front, I didn't see anything I had read about (though, to be fair, I hadn't expected to - Burma's human rights abuses take place almost entirely in areas closed-off to tourists).

I obviously didn't leave Burma feeling human rights abuses didn't exist. But my understanding of Burma became more nuanced. I stopped talking incessantly about injustices, and decided, in my fourth year, to do a thesis based in large part on Burmese history.

For over a year I toiled away, reading colonial-era, scholarly and Burmese books and articles on ethnography, history, religion, philosophy, culture and a host of other topics.

The experience left me with a strange feeling - sympathy for what I had considered dictatorial regimes, and an iota (only an iota!) of contempt for the many "democratic" activists so busy in the Burmese diaspora community. Despite knowing more about Burma's sordid past, I actually found myself less likely to criticize the regime. Paradoxically, the process of studying the country intensely had left me more aware than ever of how little I knew. Yes, the regime had used child soldiers and horrific tactics to fight rebel armies, but the rebel armies were themselves using the same tactics. The central government was not democratic, but it was difficult to imagine what it would look like if it were.

Still, I subscribed to pro-democracy NGO's mailing lists, I read every email suspiciously. I read briefs from human rights organizations, and was amazed at how confused they left me. I was more intensely aware than ever of how far Burma had fallen, how a country that had once exported food now relied on aid to feed its people, how its civil wars had ravaged so much of the country. But none of the reports gave any indication of what could be better. Burma had been democratic for 14 years, and the "democratic" experiment had failed miserably.

While I had once vocally supported pro-democracy NGOs and believed there was a "solution" to Burma's problems, the process of learning Burmese history left me deeply convinced change, if it were to occur, would come through Burmese people, ideas and systems. A return to Burma's pre-colonial past, even if only philosophically, was vastly preferable to the external intervention of another country. I became increasingly frustrated with people who argued other countries needed to intervene. Why couldn't the Burmese help themselves?

I was reminded of my thought process recently, when the KONY2012 video burst into the public consciousness. Twitter mentions of Joseph Kony's name exploded, with celebrities tweeting in support of the "awareness" campaign. Two million people saw the video in two days. After four, the total was around 50 million.

After studying Burma, which has more child soldiers than Uganda, I could only react to the Kony campaign with disgust and frustration. It takes what is, on paper, a noble cause - the removal of a despicable warlord - and turns it into a patriarchal, simplistic call to violence.

What frustrated me most about the whole campaign was how closely it mirrored the Burmese campaigns that frustrated me so much. It seemed to argue we, as Westerners, were uniquely privileged to "help" the rest of the world, and that all those who were not rich or middle-class essentially had no agency. And it summarized a conflict that had its roots in hundreds of years of history suspiciously neatly; here are the heroes, here are the villains. The solutions offered were also suspiciously neat - eliminate Kony at all costs.

Thankfully for me, an astonishing number of Internet commentators, academics and journalists have spoken out against the video.

Before we involve ourselves in other parts of the world, whether it's to fight a warlord or starvation, we would be wise to educate ourselves about the region's history. It isn't simply enough to know there exist armies of child soldiers in the world. The broader questions, the questions that actually stand a chance of "helping" are those that address, in some substantial way, why these problems have arisen in the first place.

And the sad truth is that an incredible number of humanitarian projects are onanistic - they help the donor (to feel good about his or herself) while doing nothing for (or hurting) the receiver. The Kony campaign is an especially bad one, but it is one of a great many. Humanitarian aid in the last few decades has created areas in the world where people don't grow food, as everyone receives food for free. Aid from western countries also typically comes with a provision the aid be purchased in the country of origin. This helps to stimulate the donor country's economy, while ultimately hurting the economy of the recipient.

I wouldn't argue all aid is useless, or that all aid ultimately hurts its recipient. But knowing the difference between useful and harmful aid is difficult. It requires slow, steady slogs through books written by interminably boring academics, steady poring through bizarrely disorganized websites (un.org is my favourite example). If we could solve the world's problems by throwing posters on the walls and having fun with our friends, the whole world would already be living in Shangri-La.

Something incredible happened in Burma in the last few months. Going against years of history and the predictions of countless international experts, their government began a sudden, jarring turn towards freedom (I'm using the word in its pre-Bushian sense), democracy and liberalization. It did so not because of "awareness" in the outside world, Twitter campaigns or donations to the few NGOs allowed to operate in the country. The real reasons for the change were personal, economic and political, but ultimately unclear. "Awareness," on the part of Westerners, certainly played no part.

Just as importantly, the country did not immediately become a Western, liberalized democracy. The military still holds great power, there will always be some degree of deeply-ingrained interethnic strife and Burma's strict Theravada Buddhism will remain important. But there is little denying that without much external humanitarian intervention, life in Burma has recently become better for its political prisoners and its minorities.

I don't mean to compare what has happened in Burma to what could happen in sub-Saharan Africa to Joseph Kony. But "awareness" is a useless goal. Knowledge is far more important.

I always loved adages growing up, with one exception. I could never understand why "charity begins at home." The answer, perhaps, is that the road to hell is paved with good intentions.