VICTORIA, B.C. — The latest Greek bailout request being debated at EU headquarters in Brussels is yet another chapter in what must surely be the longest playing national debt drama in modern history.

Ironically, the country should never have been allowed to join the Eurozone in the first place. Greece was granted membership in 2001 after presenting false data showing the country had achieved the necessary debt and deficit targets. Three years later, the government finally admitted it had fudged its books to gain entry.

But when Greece assumed the mantle of a Eurozone member, financial markets overlooked the country's over-extended balance sheet. Greeks went on a new borrowing and spending spree, while again hiding the true size of their deficits from Brussels through a devious derivative scheme managed by Goldman Sacks.

By the time an inquiry into that second fraudulent act was announced in early 2010, Greece's national debt had more than doubled to a whopping €330 billion. The country's debt ratings plummeted to junk bond status, putting it mere just weeks away from sovereign debt default.

Eurozone members faced a crucial decision: cut Greece loose or bail them out. They had every right to expel Greece from the Eurozone on the basis of its fraudulent entry, followed by a second fraud that hid the country's extravagantly high deficits. Choosing to implement a bailout meant the Eurozone had to overlook these transgressions and also trust that the country's long entrenched dysfunctional governance, out of control spending, bloated and unaccountable public service, business crippling bureaucracy and institutionalized corruption could be miraculously changed.

This reality was summed up by German Economy Member Michael Fuchs as Eurozone members debated their choice in Brussels, "If we start now, where do we stop"?

In my February 22, 2010 column written during that debate, I stated, "An EU bailout of Greece would surely lead to the rampant spread of a moral hazard disease deadly to the future of the world's largest economic zone". Cutting Greece loose then would not only have meant a much stronger Eurozone today, but would also have forced Greeks to face their entrenched dysfunctions and begin dealing with them.

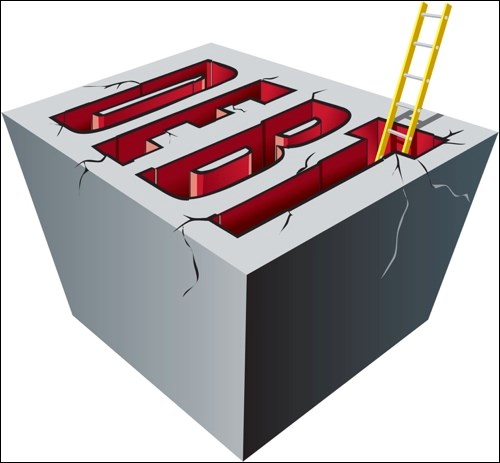

Now, five years later, a much weakened Eurozone again looks down the Greek debt black hole as a debate about releasing further bailout funds rages. Despite receiving €214 billion in bailouts since 2010, the country's debt has actually risen, now standing at some €340 billion. Hardly evidence of the alleged drastic spending cuts that have seen anti-austerity Greeks demonstrating and burning in effigy German Chancellor Angela Merkel, leader of their main benefactor. And a newly-elected Socialist government is vowing to ratchet up spending and reverse hard-won structural reforms has just been elected. Just how much is enough to cut Greece loose?

Many commentators contend that the shrinkage of the Greek economy since the bailout spending reform conditions were implemented demonstrates that austerity has failed. Reaching that conclusion requires denial of the fundamental principle of actions and consequences that apply to countries as well as families and individuals.

Consider the case of a household whose members chronically live beyond their means. They have no savings and their bank account is constantly in overdraft. Rather than cutting back, they obtain multiple credit cards by hiding their true financial situation, but those credit cards are soon maxed out. In desperation, they turn to financially responsible cousins to help them through, again hiding the true scale of their spendthrift ways. Finally, the family defaults on its loans, triggering loss of home, car and other possessions. But instead of recognizing that they were the architects of their own misfortune, they consider themselves victims of the big-bad mortgage, car loan and credit card companies. And they even vilify their generous relatives for refusing to lend more money.

Greece's problems have not been caused by austerity but by decades of irresponsible spending and corrupt behaviour. Expecting that a debt problem will be solved by more debt simply defies common sense and reality. Believing this myth will only make the debt hole Greeks have dug themselves even deeper, and the challenges of climbing back out ever more unlikely.

— Gwyn Morgan is a retired Canadian business leader who has been a director of five global corporations.

www.troymedia.com