Last September, the U.S. Federal Reserve at long last began its so-called quantitative tightening (QT), gradually lowering its holdings of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. How should investors respond? If QE was positive for asset prices, then simple logic suggests that QT would be negative. Undoubtedly, this reasoning will be endlessly promoted by many pundits. And the sudden return of stock market volatility in early February only seemed to confirm their view. If only it were that simple.

We do not dispute Newton’s Third Law: Every action has an equal and opposite reaction. Every surge has a backwash. Booms are followed by busts. And no rally lasts forever.

But financial markets do not conform to Newtonian theory. In physics, principles and formulas are universal and, importantly, durable. Their permanency doesn’t fade. Conversely, financial markets – much to the chagrin of those still carrying the torch for the Efficient Market Hypothesis – are driven by ephemeral opinions. Yes, they are arenas of action and reaction. But they are also layered with dialectics of suppositions, crowd-driven opinions, and, notably, flawed assumptions. Unlike in physics, what’s right in one regime will be wrong in the next.

Therein lies the rub. A widespread misunderstanding of QE has defined the post-crisis policy period. Most simply got it wrong, forecasting that the monetary largesse created in response to 2008’s financial crisis would lead to soaring inflation and crashing bond markets. The opposite actually occurred. Bond yields shrank across the world (some going subterranean), and deflationary forces loomed large.

In her final days as the Fed’s chairwoman, Janet Yellen even came close to admitting that QE is still poorly understood by the Fed: “We believe we understand pretty well what the effects are on the economy.” Translation: It’s complicated.

What did the consensus miss? They misread the transmission dynamics of QE. What is now clearly known (and forecast as early as 2009 by your favourite Canadian macro managers) is that QE had more impact on the financial economy than the real economy. The liquidity created was distributed to capital owners (i.e., the wealthy) who have a far lower marginal propensity to consume compared with the lower and middle classes. Thus, the injected liquidity boosted asset prices rather than being multiplied by the credit and banking systems. This at least partially explains the apparent paradox of rampant asset price inflation with lower consumer price inflation.

Given the above, a useful exercise is to ask, if most market participants missed QE, what could we miss now? This is the symmetry investors should focus on.

To start, we must acknowledge that QT is unprecedented. No one knows for sure what may unfold. However, there are strong reasons to believe that the Fed’s actions will have less impact than they have in the recent past. Retrospectively, and perhaps as would be expected, QE had a bigger impact the closer it was to the global financial crisis. A comprehensive study by the Bank of England in 2016 found that QE had double the effect on economic growth during the panic period of the financial crisis compared with later iterations.*

Removing QE (when markets are functioning well) is very likely to have far less impact than if markets were in turmoil. Today, the actions of central banks have become predictable, even boring. Every major world central bank is committed to a gradualist approach. Therefore, compared with the fast-moving dynamics of QE during the financial crisis (when central bankers were desperately trying to boost confidence in the entire financial system), QT will be a glacial affair that plays out over several years. It is not the equal and opposite of QE.

Investment implications

QT will have some impact on markets. However, it will not be the Armageddon scenario currently being portrayed in much financial commentary. In the months ahead, beware of luxuriating in the polemics of many well-known bears. That was not a winning portfolio strategy since the crisis, and it will not be one now.

* http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/research/Pages/workingpapers/2016/swp624.aspx

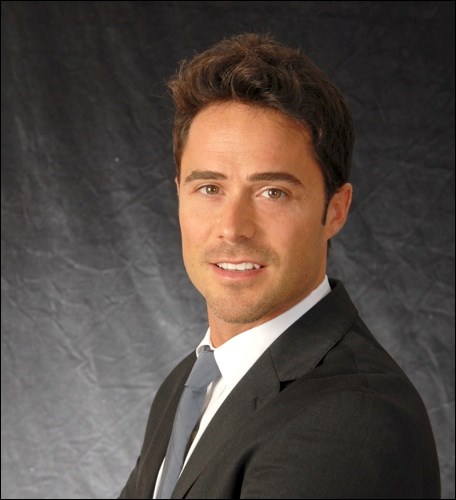

Tyler Mordy, CFA, is President and CIO for Forstrong Global Asset Management Inc., engaged in top-down strategy, investment policy, and securities selection. He specializes in global investment strategy and ETF trends. This article first appeared in Forstrong’s December 2017 issue of Super Trends and Tactical Views. Used with permission. You can reach Tyler by phone at Forstrong Global, toll-free 1-888-419-6715, or by email at [email protected]. Follow Tyler on Twitter at @TylerMordy and @ForstrongGlobal.