At the outset I must give credit to Irene Ternier Gordon whose wonderful book People on the Move (The Métis of the Western Plains) provides the backdrop for this essay.

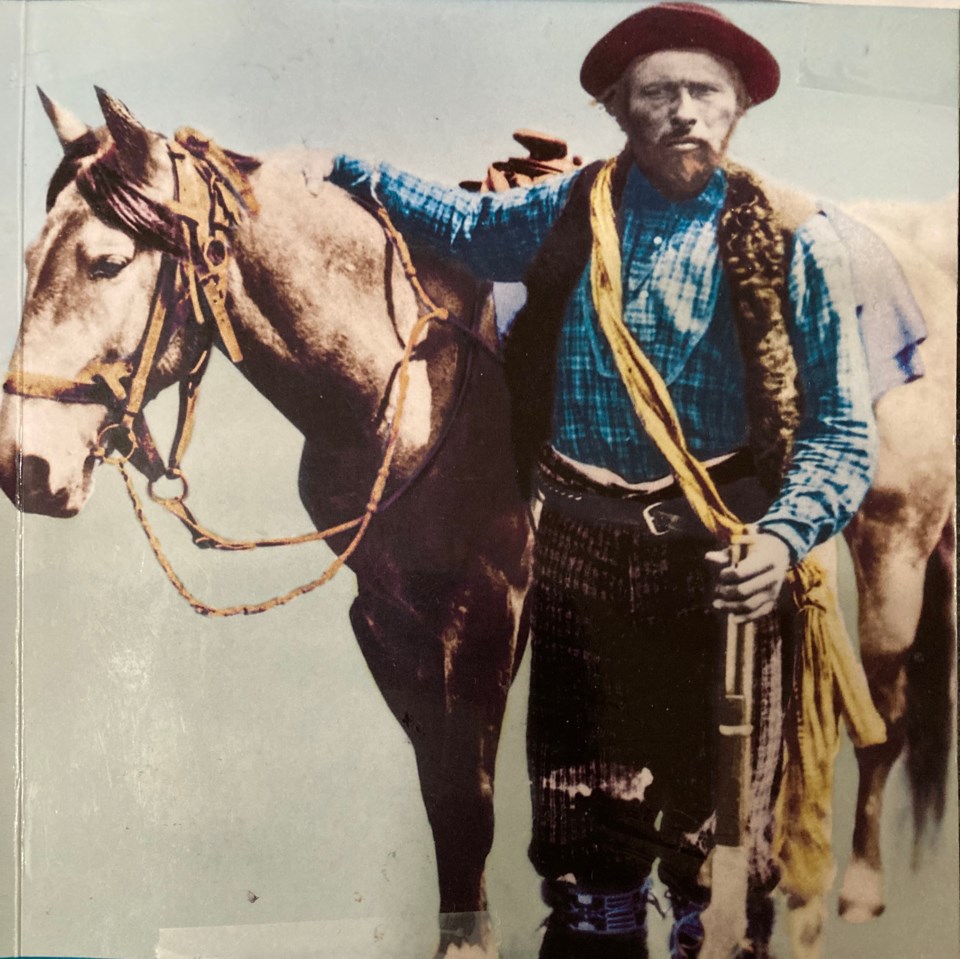

Gabriel Dumont was almost as well-known as his leader, Louis Riel. He wasn’t tall and he was built like a barrel, but he was immensely strong. He could pick up a bale of buffalo hides weighing in excess of 400 pounds and push it over the side railing of a Red River cart. He could also ride a horse like a Plains Cree warrior who were known for their great skill and prowess with horses. And Gabriel was an exceptional marksman. He could light a match at 50 paces with his Winchester carbine. After the Resistance, Gabriel Joined Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show in the United States for a time. Americans had never seen a man who could ride and shoot like Gabriel Dumont.

Yes, the Métis were a hardy lot. William Francis Butler, a successful portrait painter, noted that the driver of dog teams, who had the ability to run 50 miles, is a great man. A missionary, Father Belcourt, wrote in the 1850s that the Metis are endowed with uncommon health and strength and that they are capable of enduring the cold and fatigue with the greatest cheerfulness.

Who were the Métis and where did they come from? Métis means mixed blood This splendid race are the descendants of the French Coureur de Bois and Cree and Saulteaux women. To the north were the descendants of Scottish fur traders and Cree women.

The Métis came from the eastern lands of the French (primarily Lower Canada) and from the north east (Scotland). Métis forefathers were from these far-flung lands. What lands and places did the Métis occupy in Western Canada, and how did they make a living?

The blossoming of Métis society and culture in the 19th century marked a fascinating and colourful era in western Canadian history. The Métis began in the area of the Red River in what is now Manitoba then spread out to occupy areas that are now Alberta and Saskatchewan. Here are the stories of the masters of the plains – Louis Riel, the charismatic leader and the legendary Gabriel Dumont, his general, Métis buffalo hunters, traders and entrepreneurs like Louis Goulet and Norbert Welsh.

Marriage customs and fancy clothing, the river parcels of land and the Catholic Church were of basic importance to Métis culture. They served to underscore their vision of nationhood. The government refused to recognize the Métis as a distinct nation separate from the rest of Canada, so it was inevitable that this would be contested on the field of battle.

By 1812, the Métis were a distinct society with their own culture, traditions and laws (the buffalo hunt and the laws of the prairie). They had their own language – Michif (French nouns and Cree verbs and words from other First Nations). In addition, the Métis economy was based on freighting supplies and furs, the buffalo hunt and pemmican.

Modes of travel

In summer, the vehicle of choice was the Red River cart. The cart was adapted from carts used by habitant farmers of Quebec. The carts were made of whatever hardwood was available and held together by wooden dowels and shaganappi. The carts were relatively stable. The carts could be converted into tents or even boats and rafts. Carts were usually pulled by a single horse. They were commonly organized in brigades of 10 or more but some could stretch up to a kilometre. Travelling in a cart was usually a family affair. Many families owned more than one cart.

In winter, the most important means of travel was by dog sled. The two types of sleds, the sledge and the carriole each harnessed in tandem. The sledge was used to haul freight. The carriole accommodated one or two persons. It consisted of a thin, flat board bent up with a straight back to lean against. It was covered with untanned buffalo hide. William Francis Butler, a portrait painter, in the early 1870s, travelled on the Saskatchewan River for 50 days with 20 different trains of dogs. Another Métis adventurer, Eben McAdams, made a marathon odyssey from Duck Lake to Dawson City. I do not have the time or space to detail his journey. But I can take sections of his dairy; this will give the reader a window into the inner workings of a truly great man.

May 8, 1899. “Charlie and I went down the river to pick gum for our boats. We left at 8 a.m. and returned at 3:45 p.m. We carried rifles in the hope of shooting a stray moose or caribou. But no luck. The river is breaking up rapidly and getting dangerous ... May 9, 1899. Began drifting at 8 a,m, and stopped at 5 p.m. … June 11, 1899. Started drifting and quit at 7 p.m. ... Saw a black bear with two cubs. Scrambled ashore with rifles but couldn’t get a shot. Bear meat would have been a welcome change from hard tack and pork.”

The 1840 buffalo hunt

William Fiddler and his son Andrew had prepared for a buffalo hunt. They had talked to each other and steeled themselves for the danger ahead. And they had prayed to the Virgin for guidance and protection. They rode west towards the thunder on the plains. Suddenly, over the rise came a herd of 50 buffalo. Andrew’s father shouted, “cut off the big bull; he can turn and gore your pony; be careful.” Andrew got in closer, steering his pony with only his legs. This allowed him to manoeuvre his rifle into position and move in closer yet. The Métis were excellent horsemen and Andrew’s endless hours of practise had paid off. Andrew listened to his father; not to do so could result in injury or death. “Closer, my son, closer,” yelled Andrew’s father at the top of his lungs. Andrew was 15 feet from the bull that was running at 25 mph. Andrew’s father brought him within five feet of the buffalo. “Now my son, now!” Andrew took aim and sent a rifle slug through a 2,000-pound bull’s heart.

Isabelle Fayant McGillis observed that, “Once we had to camp for more than three days at the crossing of the Milk River to let the buffalo go by. They kept going north like a big black river, turning aside for nothing. On the second day neither the beginning nor the end of the herd was seen.” At the beginning of the 19th century, the great herds seemed inexhaustible – never ending. But by 1870, only a few hundred remained. During the first half of the 19th century, the buffalo hunt defined the Métis more than anything else.

The 1840 buffalo hunt

By the 1820s buffalo hunts had become extremely large, so large in fact that they had to be organized like a military operation. The 1840 hunt included 1,210 red river carts, 620 men, 650 women, 360 children, 586 oxen, 655 cart horses and 450 buffalo runner horses. It was a tremendously exciting time. The hunt garnered over a million pounds of meat and hides.

The laws of the hunt were strictly enforced. No one could leave the camp without permission. No one could run buffalo until the order was given. Every man had to take a turn in patrolling the camp and guarding at night. Penalties for breaching these laws were severe. Men were flogged for a third offence.

At the beginning of each day, scouts headed out to look for buffalo. When a large herd was found, 400 men and their horses waited until the captain give the order to go. The buffalo hunt lasted for about two hours. Experienced hunters could kill up to 10 to 12 animals. Injuries were high. Angry bulls could gore a horse and rider. Horses on rocky ground also caused many injuries. After taking stock, 1,375 buffalo tongues were brought into camp. It was time for a celebration. Fiddles came out and strong drinks were poured.

As dangerous as the buffalo hunt was, the spectre of armed conflict with the Lakota Sioux, traditional enemies of the Métis, was a daunting possibility. The Métis engaged the Sioux at the battle of Grand Coteau on the Missouri River (a famous battle that became entrenched in Métis folklore). The battle lasted about six hours. The Métis lost one man and 16 livestock. The Sioux, having lost 80 warriors and 65 horses, retreated. The Métis had decisively won the battle.

Dressing the buffalo

After the hunt was over, the hard work began. The carcasses had to be skinned and the meat cut up. The hides of older animals were scraped of hair and cut into quarter-inch strips called shaganappi which was dried and soaked in water. It was extremely strong; cart wheels bound with this material would last a summer. Sinews were made into thread, which was three times as strong as ordinary thread. They were used to sew leather tents, clothing and pemmican bags. Virtually all parts of the buffalo were used – for food, and hides were an important material for clothing, shelter and saddles. Even the horns were used for coat hooks.

The end of the buffalo hunt

In 1800 there were 50 to 60 million buffalo on the Great Plains. By 1870, only about 700 remained. The last great buffalo hunt took place in 1876 when the buffalo were nearly extinct. Both the American and Canadian governments encouraged the extermination of the buffalo to prepare the land for agriculture. But there were other reasons for the end of the buffalo. The use of firearms meant that everyone could efficiently kill buffalo. These Included the Indigenous hunters - the Plains Cree, the Blackfoot and the Saulteaux. Professional hunters were brought in by the national railways to kill buffalo for meat for the railroad men. And there were hunters who killed large numbers of animals for sport – for their tongues. The slaughter of tens of millions of buffalo is one the great tragedies of the 19th century. For the Métis and First Nations their livelihood was taken. The end of the great beasts meant that they would have to find a new economy. This would prove to be extraordinarily difficult.

Métis independence

The drive for Métis independence took place in what is now Saskatchewan. The original resistance took place in 1869-70 at Red River settlement in Manitoba, and another in 1884. The tragic events of the Resistance ended in central Saskatchewan and forever changed the destiny of this stalwart people.

Following the 1885 Northwest Resistance, and the execution of Louis Riel, the vast influx of white settlers and the failure of the scrip system, greatly disrupted the Métis traditional lifestyle. Most Métis would lose out in the prairie west's new social and economic landscape as newcomers flooded the area.

The Trial of Louis Riel

Among the spectators are the lieutenant- governor, officers of the militia and Mounties. Mrs. Richardson (wife of the judge), Mrs. Middleton (wife of general Middleton, who will testify), Miss Osler (daughter of one of the counsel) and other ladies of social eminence. The colours of the ladies' hats and dresses and the scarlet uniforms of the officers lend the courtroom the aspect of a gala opening as counsel arrives. They are dressed in pleated white shirts and white ties and they wear black gowns. No wigs. This finery must have caused Louis a great deal of distress. The courtroom was dressed to the nines. Everyone, including Louis, knew he would have to endure a gruesome trial before he was sentenced. Yes, a gala affair, festive even. Everyone knows in the courtroom that Louis Riel does not have a chance despite his spirited defence and intellectual superiority.

Insults from the Crown were hurled thick and heavy. The Crown said that on, “March 18, Riel sent out a large body of men who busied themselves looting and taking prisoners. Looting stores at or near Batoche.” And so the trial progressed (or regressed as the case may be).

At Riel’s sentencing, the judge, in lofty, superior terms, related that, “you have committed the most pernicious and grievous crime a man can commit.” Now the judge had one last duty to commit. Riel is taken to the guard room and told to prepare to “meet your end.” And this Riel did – setting his sights on God and setting a moral example for his people.

Métis self-government

The Métis of Canada have been fighting for recognition of their indigenous rights and the inherent right to practice them, until Danial versus Canada (Indian Affairs and Northern Development) was settled in 2016. Neither the government of Saskatchewan nor Canada wanted to hold responsibility for negotiating with the Métis.

After the Danial versus Canada decision, the government of Canada and the Métis Nation (represented by the Métis National Council and members of its board of governors) signed the Métis National Accord on April 13, 2017. This started the process of repairing the relationship between the Crown and the Métis Nation – to address the wrongs committed against Métis people and the Métis Nation and to move forward on recognition of Métis rights, and to address the needs and issues facing Métis people.

On July 20, 2018, the Métis Nation – Saskatchewan and Canada signed the Framework Agreement for Advancing Reconciliation. This established the mechanism by which the negotiations on the shared objectives would be conducted. As negotiations progressed between Canada and the Métis Nation – Saskatchewan, along with the Métis Nation of Ontario and the Métis Nation of Alberta, signed the Métis Recognition and Self Government Agreement with Canada on June 27, 2019.

The Métis Nation has come of age. Métis Nation, Saskatchewan president , Glen McCallum shook hands with a Parks Canada representative to cement a land transfer ceremony in Batoche on Friday June 22 which resulted in approximately 690 hectares being returned as sacred to the Métis people.

This essay will finish with a cross-section of Métis cultural venues:

Michif. In an article titled Breathing life into Michif, Samson Lamontagne noted “there are amazing and fluent speakers from just the sparks that other educators in my community are igniting right now. We're just the beginning. What the kids and other people do with this is going to be amazing.” (Source: STF Bulletin, Fall, 2022, p.6).

Red River cart. Two master craftsmen, Armand Jerome and Don Benoit, were responsible for the revival of the Red River cart. Great skill is required to build a Red River cart. Spokes must be fitted into a hub, a horse must be trained to lead a cart and hand rasping an axle end is necessary. (Our Canada, Aug.-Sept., 2022, pp. 26-27)

Métis Cultural Days. Métis Cultural Days recently celebrated the Year of the Family. Shirley Isbister, president of the Central Urban Métis Federation Inc. (CUMFI) urged families to come out and support the festival. CUFMI created to the festival in 2018 to showcase Métis culture, history and language. (Source: Saskatoon StarPhoenix, Sept. 8, 2008)

Métis perspective. The exhibition Kwaata-nihtaawakihk – a Hard Birth brings a Métis perspective to archival materials as well as to historical and contemporary art that is used to mark the recent 150th anniversary of the founding of Manitoba.

Métis artist makes mark. Indigenous tattoo artist Stacey Fayant celebrates her heritage and culture with beads and ink. Her strong pride in her culture is a “bold stance” against the racism her family has faced over the years. When she found out about Indigenous tattooing, she really knew she had to be part of it, bringing it back and revitalizing it.

The Willow Bunch Giant. Edouard Beaupre stood eight feet two inches tall, which made him the tallest man in Canada. He was born on Jan. 9, 1881. And he was incredibly strong. Edouard could have used his strength to intimidate others but he did not. Instead, he was a very peaceful man. The story of Edouard Beaupre's life is included in The History of the Métis of Willow Bunch.

Conclusion. The story of the Métis of the western plains is about a people on the move. The Métis dominated the western plains for many decades. They were hunters and freighters. The buffalo was central to the Métis way of life, and the Métis lived by the laws of the prairie. Tragedy struck with the Resistance in 1885 and many Métis were reduced to poverty. But eventually they climbed out of this dark pit and became prosperous once again. Finally, this story concludes with Métis independence and self government.

(Source: Internet (Wikipedia); Bridges, The Star Phoenix, June 9, 2022; Canada's History, August-September, 2022; Saskatchewan Folklore, Spring 2012; A people on the move: The Métis of the western plains, Irene Ternier Gordon, 2009; photo credit – Chyla Cardinal.; From Duck Lake to Dawson City, Ebenezer McAdam; The Trial of Louis Riel, John Coulter)