Telling the story gets a little easier each time around. Living the story was an unsettling nightmare.

Rounded up and herded into a cattle truck along with his sisters and other youngsters from a Moose Mountain First Nations community and shipped off to a residential school in the Qu’Appelle Valley, 10-year-old Armand McArthur quickly honed his defensive coping skills.

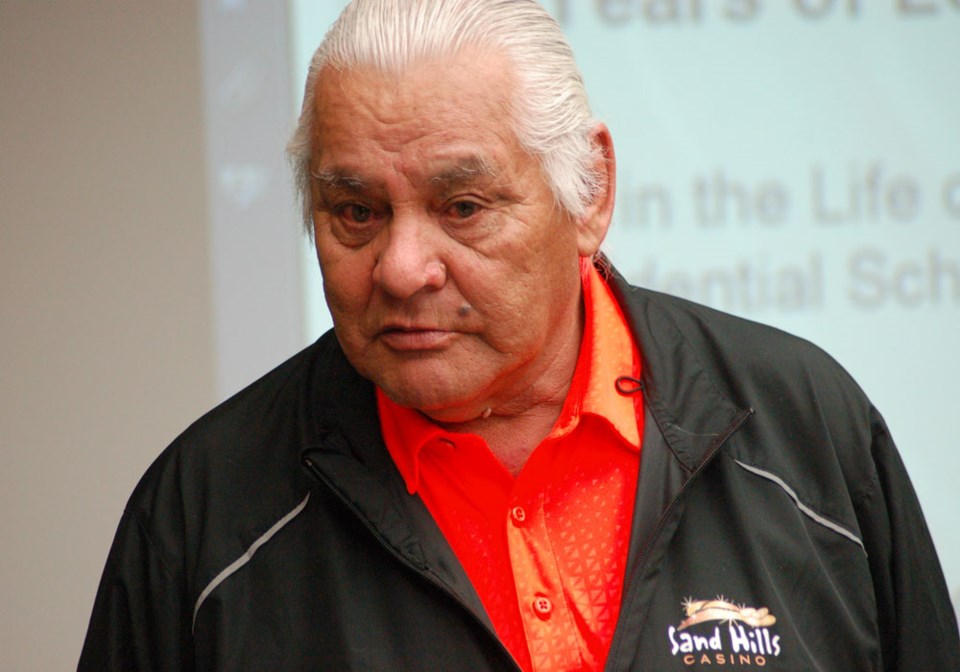

Being whipped on a regular basis and witnessing other youngsters undergoing the same ritual, McArthur, a tribal elder and respected First Nations educator and instructor, told the trustees of the South East Cornerstone Public School Division, how he learned to weep quietly so as to not attract the attention of the nuns and priests who were wielding the punishment tools. McArthur addressed the trustees during their open business session in the division’s head office on March 19.

In 1958 McArthur was hustled into the cattle truck along with a younger and older sister and several other students from the reserve. They had no idea where they were going, he told the board members, but after a few hours on a dusty road they were dispatched to a “big red building with a lot of people dressed in black clothes walking around. I didn’t know what they were or who they were,” he said.

He was soon separated from his sisters and sent to a part of the building designated as the “small boys area.” He learned this sector was housing boys from the age of five to 12.

He got a look at a gymnasium and then a shower room where the youngsters were required to strip and undergo a cold shower.

“Of course, we were naturally shy, so this was really difficult, and then we didn’t get our clothes back. Instead we had another couple of buckets of liquid poured on us and it really burned. Most of us got red rashes right away. We tried to find our clothes, but instead we were led to another room, and I was told my number was 58, I was handed some clothes and every piece had 58 written on a tag.”

McArthur said the humiliation continued as they were led to a series of benches, and he took his position in front of the space that was marked 58, his new identity.

“So, that’s where I sat, and we were told that if we moved, we were in trouble.”

Supper hour came and then a dormitory assignment where 58 was matched with his bed number 58.

Their first instruction came from the nuns, who showed them how to make a bed.

“I had never made a bed. We usually slept in buffalo robes back home,” he said.

He recalled having to make his bed four times on the fifth morning before it qualified as being satisfactory by the overseeing nuns. He related how one unfortunate six-year-old continually struggled with bed making and was punished by having to make every bed in the 20-bed dormitory for several days, until he learned how to do it in the proper military style. McArthur said scenes like those stayed with him over all these decades.

Early breakfast was usually burned porridge or eggs, served on metal plates. It was so bad, he said he often needed to throw-up his morning meal. This was followed by something the priests and nuns called Benediction at 6:30 a.m.

“Benediction meant we kneeled for a half hour,” he said.

The boys were assigned to a variety of farm labour jobs until noon and then returned to the school and regular lessons until 5 p.m.

“We got a little time to play then, before supper at 6 o’clock and bed by eight,” he said.

It was that time of day, McArthur said, where he would be overcome by homesickness or a general lonesome feeling. But he learned quickly, that those feelings were not to be displayed, at least not in front of the people in the black clothes, or else you received a whipping.

“Yes, we were whipped for being lonesome,” he said. “That’s where I learned to cry quietly, so I wouldn’t be whipped.”

Just sitting on those benches required the development of several other small skills that had to be learned to avoid the switch. McArthur demonstrated to the trustees how he learned to fold and grip his hands to eliminate the usual childish fidgety movements and squirming around on the seat.

“After we got a whipping, we’d have to go back and sit quietly and that was very painful because it burned so hard, and we had to sit so quietly,” he said.

Transportation was not as easily available then as it is today, so McArthur said he was simply astonished come April when he was brought to a room where he got to see his mother.

“My mother came to visit us. She had hitchhiked to the school and we got to visit in the visitors’ room for a half hour. It was the most beautiful sight in the world for me, I saw my mother’s face again. I got to talk with her.”

Of course he wasn’t able to tell her what was going on because the visit and conversation was closely monitored. Too soon the time was up, but as he left, he passed his sister in the hall, who was also being allowed a half-hour visit, which made him doubly happy.

“I remember as I got up to leave my mother, I began to cry and she told me ‘go and don’t look back’ and I didn’t.”

After that, McArthur said he formulated a plan.

“The first chance I got, I knew I was going to run.”

The attempt was foiled early. He made it to the valley edge to some bushes, but he was soon spotted and captured by the priests who brought him back to the school and whipped him in front of the other boys who were arranged in a circle around him.

The second run to freedom was slightly more successful. McArthur said the first run was one of desperation. The second one had a better plan.

“I knew my directions. I used the skills my grandpa had taught me about tracking, directions, finding my way in the bush. I made it home by walking around the lake. Grandpa had shown me how to follow trails, tree moss, sun and to trust nobody. It took me awhile. After two days I was really hungry. I came to a farmyard and the farmer had put some dog food out, so I ate the food from the dog dish because I knew I couldn’t raid the garden. That wouldn’t be right.” It was probably too early in the growing season for the vegetable gardens to be yielding much anyway.

The Aboriginal educator said he certainly caught his mother by surprise.

“But she thought the people running the school were sacred people, so she said I had to return, but I had only built up a great hatred. Then I remembered another lesson grandpa had taught me. He had taught me how to forgive.”

He went back to the school. When he finally got out he entered into a successful marriage of 47 years with his wife who had gone through a similar excruciating time where she had seen young girls abused and impregnated unwillingly.

“But it wasn’t until 2010 that we finally told each other our story. She had been abused by priests, she heard my story and the door opened to our relationship that just became stronger,” McArthur said. “We talked about the nightmares we had, and now the opportunity to talk about it helps me heal.”

In introducing McArthur to the trustees, Aaron Hiske, curriculum co-ordinator for the school division, said he had urged the native elder to record his story on video, so the message could be taken to each of the 38 schools in the division to be viewed by the students before the official federal “letter of apology,” signed by Prime Minister Harper would be placed in a conspicuous spot in each building, as a reminder for all to pay attention to lessons taught by history.

“But he didn’t want that. He said that telling the story in person, was what he needed to do because each time he did, it became a little easier.”

McArthur nodded, and added the hurt was diminished with each retelling.

“Other kids ran away. Some did not make it home like I did. I had a deep hatred for the Catholic church for a long time, but I remembered my grandfather’s lesson. I hope this never happens again and mine is just one story,” said McArthur.

“Our kids have heard the story, and retelling it has helped his healing,” said Hiske, who added that supporting documents and handbooks are available for students of all ages and a female elder/counsellor has been added to the program, teaching lessons of reconciliation and the official federal apology as the nations build a more meaningful relationship.

“The discussions tie in very well with curriculums. We can learn about sweat lodges and medicine wheels and we’re learning that you just can’t lump First Nations issues into one tidy block and consider the work done. Each nations has their story,” said Hiske.

Audrey Trombley, chairwoman of the board, thanked McArthur for sharing his story with this generation of educational trustees and the school division’s students.