REGINA — Moose Jaw may have never hosted Al Capone. Its tunnels weren’t the dens of debauchery that billboards and bored Bills say they were. Even its bizarre name has minimal connection to deer maxilla, rendering Mac, the 34-foot concrete sculpture dubbed the "largest moose in the world," another of the city’s counterfeit creative licences.

After clearing away the bull-moose shit, one finds that the biggest real thing to occupy "The Jaw" was a five-foot-five Asian man who prospered there from 1905 till 1921, when he vanished, only to turn up more than a decade later in Detroit as an FBI-suspected spy sent to incite African-Americans against their government. The modest Moose Javian had become Major Satokata Takahashi, and, nearly 70 years after his death, he’s here to make jaws drop.

Last Samurai, First Pastor

The man the FBI thought was a much younger Tokyoite named Takahashi was actually born Naka Nakane (中根中) in 1870 in Kitsuki, Japan. The Land of the Rising Sun had set on feudal society, so the Nakanes, who sustained several generations of samurai, were squinting at an opening world. What emerged the brightest, at least for the Nakane boys, was Christianity.

After centuries of exclusion and execution, Christian missionaries had returned to Japan. One of these was Samuel Wainright, an American Methodist who taught the Bible and English with his wife in Ōita prefecture, where the eldest Nakane son, Naka, was attending school. Naka became one of Wainright’s pupils and the first Methodist baptized in the area. Naka’s younger brother, Masato, was baptized the following year.

In 1889, Naka was part of the inaugural class of Kwansei Gakuin, a private Christian university still in operation. He spread his wings as a preacher, notably railing against prostitution. After further training, Naka became a full-fledged missionary. He resettled in his hometown, founding Kitsuki Church and serving as its first pastor. He was 22.

However, in 1895, Naka was expelled from the parish. Although no explanation exists, a succeeding pastor surmised that his fiery spirit may have conflicted with expectations of chastity. Naka wed a woman named Sao, but she died at age 20. Then he had an extramarital tryst with the daughter of a sake brewer that bore two children. Unsatisfied being a defrocked bastard father relegated to teaching English at a junior high school, Naka took the reverse course of Wainright, abandoning the first of his families for the West.

Rising Sun Meets Living Skies

Naka landed in Victoria, BC, Canada, in 1904. From there he moved to Moose Jaw, then the largest city in the new province of Saskatchewan. Work and opportunity offered by the Canadian Pacific Railway brought Asian immigrants to the city, first Chinese nationals in the 1880s and later Japanese like Naka. In 1911, three-fourths of Sask’s Japanese residents lived in the Moose Jaw district.

Naka worked/lived at the CPR hotel and attended Western Business College. He often went by George, which is no surprise considering his name was rendered by officials as Nata Nakane, Naka Nakame, Naka Makane, Nasa Nakane, N Nakani, Naka Nakama, G Nahani, and M Nakanee.

Naka made his own name for himself by rising in status. He became a citizen of the British Empire and married an English woman, Annie Craddock, following a long-distance romance. “Marries Japanese” is how Victoria’s Daily Colonist announced their nuptials, which took place in Saint John, New Brunswick, on Feb. 10, 1910. This was at a time when reverends rejected mixed-race marriages and newspapers instructed readers to “never marry an Oriental.”

Ignoring their advice, Annie went back with Naka to Moose Jaw, where they settled into a house at 98 Fairford St E. Excluding one that died in infancy, they had four children. By 1912, Naka was running Carlton Cafe on River St. By 1918, he also operated La Hale Lodge. Unlike the Asian patriarch of an off-white family, an Asian proprietor was no anomaly in 1910s Moose Jaw, which had a Japanese-owned dental clinic and dozens of Chinese-owned businesses, comprising nearly half the restaurants in the city.

That it wasn’t an anomaly disturbed many white people—to such a degree that, in March 1912, Saskatchewan’s government voted to ban “any Japanese, Chinaman or other Oriental person” from employing white females, effective May 1.

The “White Women's Labor Law” implied that Asian employers were too depraved and white women too pure to mix in a workplace. Saskatchewan’s small but significant Asian population was outraged, as were certain non-Asians, including Caucasian women who had no beef with Asian bosses. Right after the vote, Saskatchewan’s attorney general William Turgeon received a letter from a concerned Moose Jaw resident. It began, “I am a Naturalized British subject, and have been doing business in Moose Jaw for the past 7 years, during which time, I have never heard of any complaint against any Japanese in this City.” The resident claimed that, except for those employed by the railway, there were less than 20 Japanese people in Saskatchewan. Even so, the bill’s passing “would be a great dishonor to our nation in general”:

. . . it would be extremely unjust to apply it to all those who are carrying on honest and straight forward business merely on account of difference of birth, and I feel it is our duty to make an appeal for the exclusion of the Japanese from this Bill.

The letter was signed, N. Nakane.

Turgeon gave a diplomatic reply and the bill passed as planned. Thankfully, Naka also contacted the Japanese government. This spurred talks between the then-allied nations, including a meeting in Regina between Turgeon and the Japanese consul to Vancouver, Chonosuke Yada. In 1913, Saskatchewan struck Japanese people from the law. Chinese people, who were scapegoated for their alleged immorality by whites and Japanese alike, remained on the bill until 1919, when all references to Asia were eliminated. However, the bill continued to target employers of colour and wasn’t repealed until 1969.

Naka’s activism endured. Already a frequent visitor to Vancouver, he helped its Japan-born residents assert their rights as naturalized British subjects during WWI. When California passed a law barring Japanese immigrants from owning land, he argued in Vancouver’s Daily News Advertiser that America had betrayed its fundamental ideals by treating his countrymen worse than those from other nations. He listed several more bills that disenfranchised Japanese-Americans and contrasted them with the noble emancipation of slaves, which may be his first published nod to black Americans, whom Naka would get to know in the next chapter of his improbable life.

Vice City

Despite turning 50 and having spent 15 years thriving in a Canadian city, Naka again bolted—this time taking his family with him to Tacoma, Washington. That’s where his brother had lived since 1911. Back in Japan, Masato graduated with a degree in literature and married Kuni, taking over her family name to become Masato Yamasaki. He followed Naka to the West in 1906, first settling in Seattle, where Kuni later landed, and then relocating with his wife to Tacoma to run its new Japanese Language School. They had two daughters who were close in age to their Canadian cousins.

The Nakanes took up residence near the school and Naka got a job as a life insurance agent. A fifth child was born in 1922. At least on the outside, they were a big, happy family with an even bigger support system.

Then, in 1926, Naka disappeared, leaving behind an enormous debt and a broken household that Masato tried to mend. Yet again, mystery shrouds his uprooting, but drinking, gambling, and a black reverend allegedly named John White are said to have contributed to the most extreme about-face from the man of many faces.

Up in Michigan

There’s a six-year gap in the Nakane story preceding his arrival in Detroit in the early ‘30s. Naka left with stolen funds and may have sowed his wild oats across multiple countries, or he may have patronized the black community he met in Tacoma. Perhaps both. Whatever the truth may be, Naka told the FBI that Reverend White sent him to preach for black people over 3,000 kilometres away.

Thus, an old, short Japanese man claiming to be a retired army major named Satokata (S.K.) Takahashi started turning heads at black churches around Detroit. Like the Japanese, black Americans were subject to racist laws which restricted their work and land. Groups such as the Nation of Islam, established in Detroit by Wallace Fard Muhammad, were trying to change that. Takahashi attended NOI meetings and even lived with one of its first ministers, Abdul Muhammad. Thinking him a fraud, Takahashi left Abdul’s circle and drew his own, Development of Our Own, which absorbed followers from the NOI.

DOO aimed to unite black Americans, black Africans, Indians, Filipinos, Japanese, and other people of color against white supremacy. Takahashi preached that Japan, being the most powerful “colored” nation, was the “darker” races’ best chance for liberation. With African-American oppression worsening alongside America-Japan relations, DOO gained thousands of members.

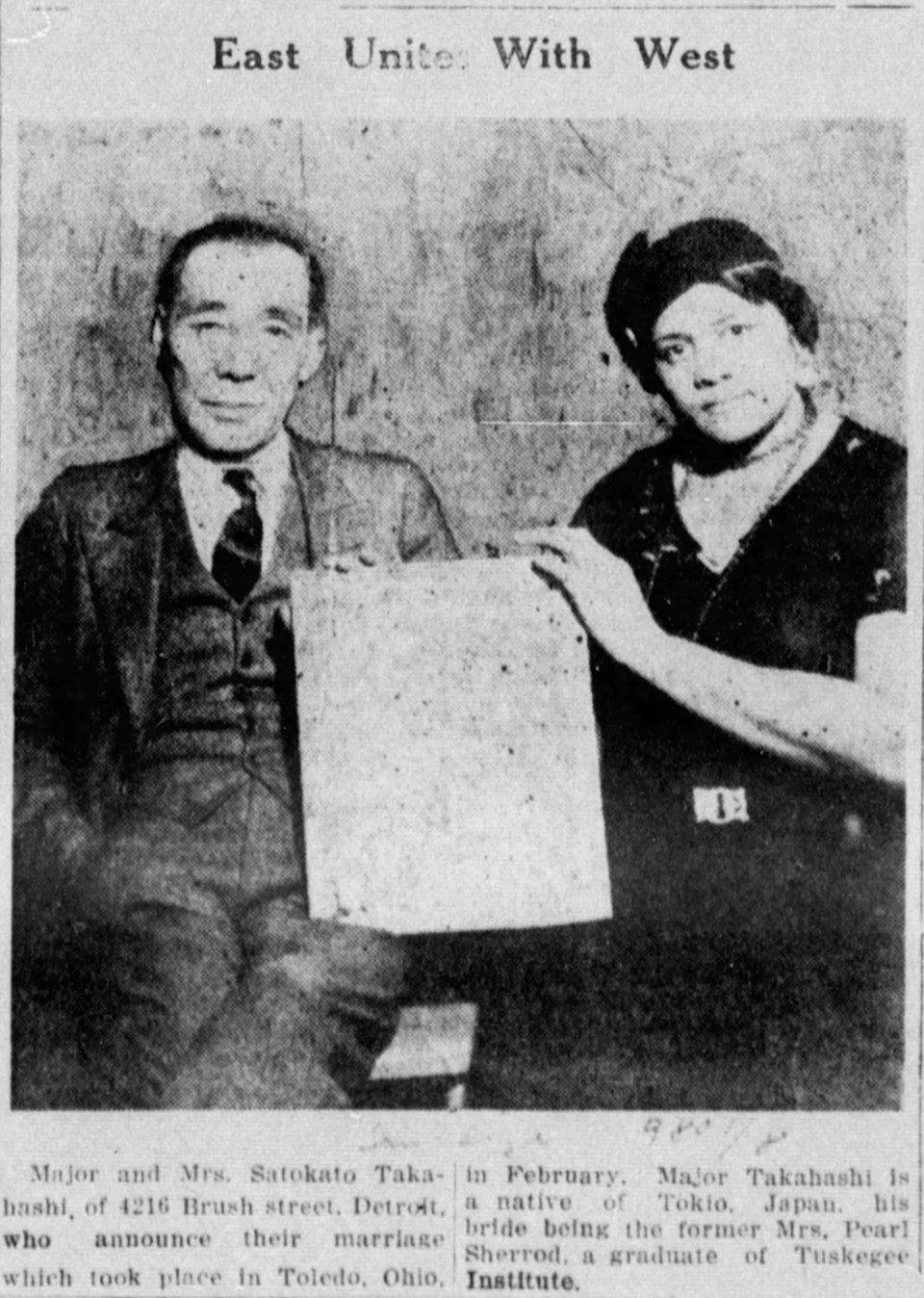

Along with strong messaging and membership, Takahashi advanced DOO with strong disciples like Policarpio Manansala, a Filipino whom he allegedly sent under assumed identities, including as a fellow Japanese, to proselytize across America; Emanuel Pharr, a chairman whom he recruited by cutting his fingers and performing a blood oath on a piece of sharkskin; and Pearl Sherrod, whom he made his DOO- and life-partner despite still being married to Annie.

Takahashi claimed to be widowed (he was, but only once). So did Annie back in Tacoma, where she worked as a hotel maid to support her fatherless children. Like in Canada, the media was thrilled to report on a marriage between a Japanese man and a woman of another race, this time black. “Japanese Weds Colored Woman” declared the Tribune Independent of Michigan.

They eloped while the groom was awaiting deportation following an undercover probe into DOO. Agents had infiltrated rallies where Takahashi promoted a violent end to white rule. In one speech, he urged “the dark races of America to overcome white supremacy and to throw the white tyrants off your backs.” In another, he attacked his own Christianity for being a tool of white domination and praised Japan for crushing it. Sufficiently triggered, the agents arrested and interrogated Takahashi. Most of his answers were false, including that he was born in Tokyo and was 10 years younger than his actual 63. Since he had been in the United States without a permit, they charged him with illegal entry.

Takahashi was deported to Japan on Apr. 20, 1934. On Aug. 29, he returned to his legally adopted home, Canada, carrying a small fortune, which he claimed was from selling property in Ōita. Over the next few years, Takahashi ran DOO from cities like Vancouver, Windsor, and Toronto, while his wife manned the frontlines in Detroit. However, their organization—and marriage—crumbled when Takahashi accused Pearl of using DOO to fund her lavish lifestyle. He fired Pearl and smuggled himself into Detroit to rebuild the org.

The Not So Little Major

Back on the Incitelin’ Circuit, Takahashi swapped disciples with Elijah Muhammad, the future NOI messiah who turned Malcolm Little into Malcolm X and Cassius Clay into Muhammad Ali. Takahashi became the Little Major and, despite conflating the letters R and L, he sermonized better than selfish and uneducated Elijah.

That is according to Cheaber Farmer (then Cheaber McIntyre), a 26-year-old mix-raced married mother of four when she replaced Elijah’s sermons with the Little Major’s. “Black” by American one-drop racial standards, Cheaber was moved by the Major; she had never seen a Japanese person before, let alone one who cared so much about her people as to lecture for their liberation in a foreign language. Although he was then 68, 13 years her mother’s senior, the two began an affair. The elderly Major was a much better lover than her husband. In fact, Cheaber playfully recalled that he didn’t need Viagra.

Once or twice a week, Cheaber would sneak to the Major’s house where he lived away from Pearl. She joined his other organ as a secretary and speechwriter. Rare for that climate, the Major was a feminist. He filled important positions with females and reproached those of his followers who believed that “women should not hold any office in an organization, nor have voice at the meetings.”

Late one June evening in 1939, as Cheaber was about to leave the Major’s house, two men in suits burst through the door, pummelled the near-70-year-old, and put Major and mistress in handcuffs. The men were immigration officers tipped off by one or both of the adulterers’ spurned spouses (or the sister of Cheaber’s spouse). The officers later alleged that the Major tried to bribe them, but Cheaber denied this and many other claims spread by the FBI. The lovers were taken in separate cars to separate locations. Cheaber was released the next day but the Major remained for extensive questioning. She never saw him again.

Through interrogation—of him, his associates, and even Masato and Annie, who pleaded ignorant to his recent extremism but acknowledged their past relations—authorities finally uncovered his true identity. Major Satokata Takahashi had become Naka Nakane again. Naka was charged with illegal entry and attempted bribery. He was fined $4,500 and sentenced to three years in federal prison.

Race Riot

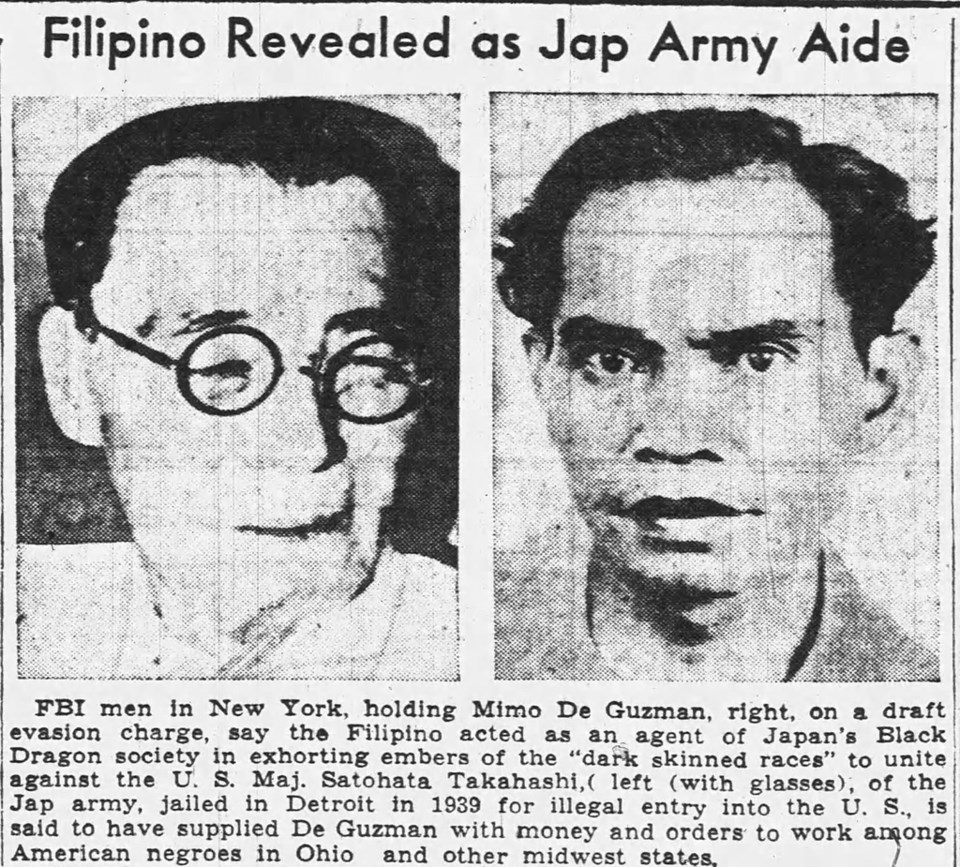

From mid-1942 to early 1943, federal agents swept through several states and arrested 100-plus racialized radicals, including Elijah Muhammad, Policarpio Manansala (under the alias Mimo De Guzman), and other leaders of the Nation of Islam (then called the Allah Temple of Islam), Pacific Movement of the Eastern World, Ethiopian Pacific Movement, and Moorish Science Temple of America. All those differently shaped yet similarly colored pieces had the same shocking connection.

They were “Takahashi’s Blacks” according to Time magazine: “cultist-puppets who, FBI believes, [were] jerked by the Japs to stir up racial trouble.” “80 Negroes In League With Japs Jailed . . . Got Ideas From Takahishi [sic]” was the headline from the Daily American. The Salt Lake Tribune summarized the FBI’s take on Takahashi, “Through the organizations he founded and inspired he taught that there were only two races—the white and the colored—and preached to American negroes that they should prepare to fight with their Japanese brethren against the white race.” Even Saskatchewan’s Leader-Post covered the conspiracy, unaware that “Major Satakata [sic] Takahashi” was one of their own.

Months later, a race riot erupted in Detroit that killed 25 black and nine white people. Authorities again blamed Naka and applied for his re-interrogation.

It turned out that, despite his three-year sentence having long expired, Naka was still imprisoned and severely imperilled.

Enemy Alien

Naka had rotten luck with Pearls. Nine days after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover personally lobbied to extend Naka’s incarceration, citing his past antagonism and ties to the Japanese government and Black Dragon Society as assets to America’s new enemy.

The Black Dragon Society was an ultranationalist paramilitary group that conspired for Japanese expansion. Naka was not an official member but he had admitted affiliation. Moreover, Manansala recalled Naka introducing himself as a spy sent by former Japanese prime minister Baron Tanaka. The alleged meeting occurred during Naka’s “blank” period of the late ‘20s and early ‘30s, which, combined with his frequent travel and mysterious wealth, lent credence to espionage.

However, Naka was a small lure in a large pond of pathological liars. Manansala had been caught in lies, as had the FBI by Cheaber, indicating that the former may have scapegoated Naka to bolster his own reputation and the latter may have exaggerated Naka’s connections to implicate black radicals and Japan, two of America’s top adversaries, in a plot to take over the country. Naka seemed to have desired that outcome and had initiated talks with the Japanese government while in Moose Jaw, and Japan likely had sent agents into African-American communities, but there’s no direct evidence (yet) that he was one of them.

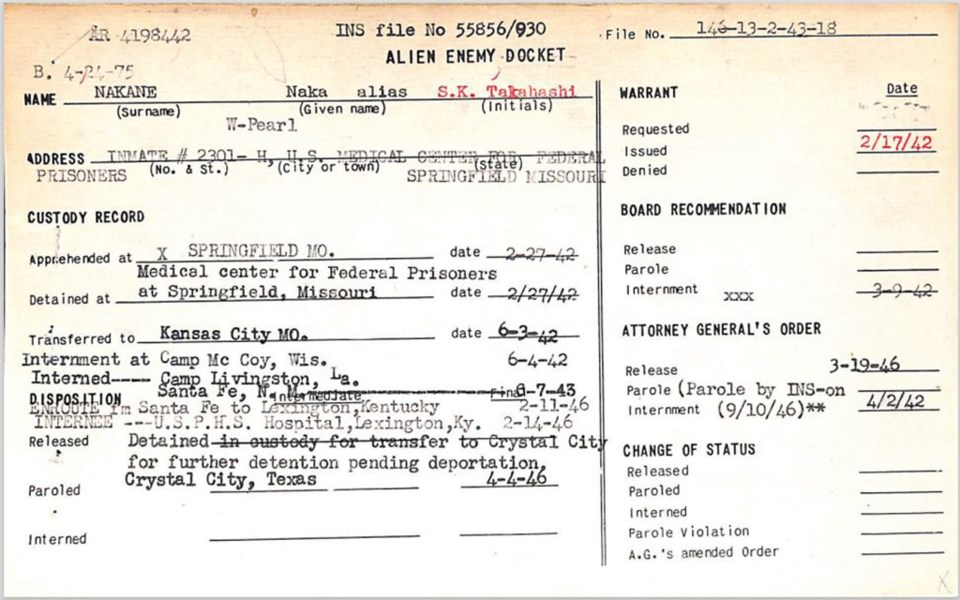

While still in custody, Naka was apprehended on Feb. 27, 1942 via Presidential Warrant as a “dangerous enemy alien.” He was interned with 140,000 other people of Japanese descent in North America. Masato, Kuni, and their one daughter (the other lived in Japan) were among them. Masato died in Lordsburg Camp. Kuni succumbed soon after her release.

The United States hoped to extract from Naka information on the Black Dragon Society and other Japan-hatched conspiracies, but by then he was well past 70 and suffering from ulcers, near-blindness, and mental impairment. He had been transferred from Kansas’s Leavenworth Penitentiary to Missouri’s Medical Center for Federal Prisoners and then interned in a number of camps before finishing at Crystal City, Texas.

Despite their troubles, Pearl supported Naka throughout his chaotic confinement.

Death of a Superman

After his three-year sentence reached seven, covering a whole year since America defeated Japan and ended WWII, Naka was paroled. Owing to his deterioration and Pearl’s determination, he was allowed to remain in America under her care.

Cheaber, whose memory of the Major still blazed when interviewed over 60 years later, heard from a fellow DOOsciple that their leader had died shortly after the war. This is corroborated by the 1950 US Census which records him as an “unable to work” lodger in Pearl’s Detroit home and an FBI file which lists his death date as Mar. 2, 1954. His resting place is unknown.

In all those decades that Cheaber couldn’t forget Naka, Naka’s families mastered forgetfulness. In Japan, they are either ignorant or dismissive of the ancestor who fought white supremacy on behalf of global people of color: “Nothing good would come of that uncle even if he lived.” In America, the “Nakane” name became “Kane” and the children’s obituaries made no mention of their renegade Japanese daddy.

Cheaber’s gone, so it’s on Saskatchewan to rekindle the flame that it helped ignite.

— Shane Fraser is a writer of fiction and nonfiction from Regina, Sask.

— Research support from Tyrone Spray; translation support from K.S.

Sources:

Introduction

Al Capone, tunnels: Jensen, P. “Moose Jaw’s Urban Legend.” Canada's History.

Moose Jaw name origin: Larsen & Libby. Moose Jaw: People, Places, History. Coteau Books.

“Largest moose in the world”: Tourism Moose Jaw site.

Height: “Alien Certificate,” Vancouver, Aug. 15, 19??, #88007.

Moose Jaw tenure: Naka’s statement to Turgeon; Henderson’s Moose Jaw Directories, 1907-1920 (1907 part of Western Canada directory; 1910 not published); Sheet 12, “List or Manifest of Alien Passengers Applying for Admission,” Port of Vancouver, June 2, 1921.

Last Samurai, First Pastor

Naka’s Japan upbringing: Idei, Y. 黒人に最も愛され、FBIに最も恐れられた日本人 (The Japanese Most Loved by Blacks and Most Feared by the FBI). Kodansha.

Rising Sun Meets Living Skies

Landing date: Sheet 180, “List or Manifest of Alien Passengers . . .” Port of Vancouver, May 24, 1907.

Moose Jaw largest city: 1906 Census of the Northwest Provinces.

History of Asian diaspora in Moose Jaw: Larsen & Libby, Moose Jaw: People, Places, History.

Sask Japanese population, Moose Jaw address: 1911 Census of Canada.

Lived/worked at CPR Hotel: 1908 Henderson's Directory.

Western Business College: Penman’s Art Journal. Sep. 1908, vol. 33.

Name variations: Henderson's Directories; Tacoma Directories; “Alien Certificate”; FBI File on Wallace Fard Muhammad.

Marriage to Annie: “Marriage. Registration Division of Saint John City and County,” Feb. 10, 1910, #002585.

Asian/white marriage opposition, history of White Women’s Labour Law, white women without beef: Backhouse, C. Colour-Coded: A Legal History of Racism in Canada, 1900-1950. University of Toronto Press.

“Never marry an Oriental”: The Leader-Post. Jan. 8, 1912.

Infant death: Moose Jaw Burial Record, Mar. 15, 1911.

Four children: “List or Manifest of Alien Passengers . . . ” Port of Vancouver, June 2, 1921.

Naka’s businesses, Asian-owned businesses: Henderson’s Directories.

White Women’s Labour Law: Original bill from March 1912.

Naka/Turgeon correspondence: 大日本外交文書 (Nihon Gaiko Monjo). 1912, vol. 1.

Naka and Japanese government, white/Japanese scapegoating of Chinese: Hosokawa, M. “Asian Immigrants and the British Empire: Canada’s ‘White Women’s Labour Laws’ in their Imperial Context.” The East Asian Journal of British History. July 2017, vol. 6.

Vancouver activism: Evanzz, K. The Messenger: The Rise and Fall of Elijah Muhammad. Pantheon Books.

California land bill: Daily News Advertiser. June 11, 1913.

Vice City

Masato’s story, Nakane house near the school, Naka’s disappearance: Idei. Japanese Most Loved by Blacks.

Naka’s employment: Tacoma Directories, 1923, 1925, 1926, 1927.

Fifth child: “Births.” The Tacoma Daily Ledger. Mar. 7, 1922.

Up in Michigan

Six-year gap, DOO absorbed NOI followers: Allen, E. "When Japan Was "Champion of the Darker Races": Satokata Takahashi and the Flowering of Black Messianic Nationalism." The Black Scholar. Winter 1994, vol. 24.

Stolen money, DOO ideology, America-Japan relations, membership total, Takahashi’s associates, blood oath, DOO infiltration, anti-Christianity speech, interrogation, selling property in Ōita, marital and organizational strife: Idei. Japanese Most Loved by Blacks.

John White, black churches, NOI affiliation: FBI File on Wallace Fard Muhammad.

African-American oppression worsening, “white tyrants” speech: “Discrimination Big Factor In Negro Unrest.” The Minneapolis Star. June 14, 1942.

Takahashi a “widower”: Toledo, Ohio Marriage Record #101725, Feb. 24, 1934.

Annie a “widow” and hotel maid: 1934 Tacoma Directory.

Deportation and return: Hill, R. The FBI's RACON: racial conditions in the United States during World War II. Northeastern University Press.

The Not So Little Major

Cheaber’s story and statements, Naka’s arrest, interrogation, sentencing: Idei. Japanese Most Loved by Blacks.

The Major’s feminism: Takahashi, S. “DEVELOPMENT OF OUR OWN.” The Tribune Independent of Michigan. Apr. 21, 1934.

Race Riot

FBI purge: Allen, “Darker Races.”

Takahashi sedition coverage: “U.S. At War: Takahashi's Blacks.” Time. Oct. 5, 1942; “80 Negroes In League With Japs Jailed.” The Daily American. Sep. 22, 1942; “FBI Reveals Jap Plot to Win Negroes.” The Salt Lake Tribune. Sep. 22, 1942; “Now Fifth Columns By Negroes, I.R.A.” The Leader-Post (via Associated Press). Sep. 22, 1942.

Riot death toll: United States Task Force on Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Violence in America: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. 1969.

Naka blamed for riot: Hill. The FBI’s RACON.

Authorities applying for re-interrogation: Idei. Japanese Most Loved by Blacks.

Enemy Alien

Hoover’s request, alleged FBI framing, Japanese spies, Masato and family’s fate: Idei. Japanese Most Loved by Blacks.

Black Dragon Society affiliation, Tanaka affiliation, release and reincarceration, Leavenworth transfer: Hill. The FBI’s RACON.

Not an official in Black Dragon Society: Kearney, R. African American Views of the Japanese: Solidarity Or Sedition? State University of New York Press.

Black Dragon questioning, internment locations, Pearl’s support: Nakane “Alien Enemy Docket” Internment Card, INS file no. 55856/930.

Death of a Superman

Parole date, under Pearl’s care: “Alien Enemy Docket.”

Cheaber’s memory, “Nothing good would come of that uncle even if he lived” from one of Masato’s daughters (translated from Japanese): Idei. Japanese Most Loved by Blacks.

“Unable to work” lodger: Sheet 3, “1950 Census Of Population And Housing,” Wayne County, Michigan #8559.

Death date: FBI File on Wallace Fard Muhammad.

Obituaries: Kanes in Contra Costa Times (Oct. 2, 2003) and Biola Connections (Spring 2007); Cheaber in Detroit Free Press (Apr. 20, 2006).