Music might not be the most obvious, but it’s definitely one of the very important parts of the military. Ahead of Remembrance Day, Cadet Instructor Cadre (CIC) Officer and Saskatchewan Pipe Band Association board member Capt. Robert Rooks, CD, talked to the Mercury about some military musical traditions associated with ceremonies and the role of music on battlefields and in regular life.

There are certain pieces of music in the military that people hear and associate with particular events, but not always do they know why these particular pieces are played and how they came about. Rooks opened up the story behind the Last Post, a piece that is played during the Remembrance Day ceremonies, as well as at funerals and which is a bugle call.

"If there is the Last Post, there must be a First Post someplace. How this came about is back when we didn't have communications like radios, cellphones and other, the military used buglers to alert officers and soldiers to what was going on," Rooks explained.

"When a regiment would be camped out during battle and nightfall comes, they set sentry posts, because at night it's more dangerous because 90 per cent of the troops go to sleep, so you had to have sentry posts. So you had a number of sentry posts guarding the area."

Rooks went on to explain that when sentries were taking their posts, sergeants would take a bugler with them and inspect each post.

"He starts at the first sentry post, and when he arrives there and everything is OK at the first post, the bugler sounds the certain bugle call, so those back at camp know that the first post has been inspected. Then they would go to every other post and when they got to the last post, the bugler would play the Last Post. Then the camp commander knew that the camp was secured," Rooks explained.

The bugle calls came from the British army and were adapted by Canadian soldiers during the First World War. The Last Post later gained symbolical meaning.

"It came to be used for soldiers' funerals because it was last of the soldier's life. And on Remembrance Day we remember all soldiers that were killed in action and one of the things we do we play is the Last Post."

The Remembrance Day ceremonies will look a bit different this year and it will be by invitations only, but Estevan will still hear the Last Post preceding the two minutes of silence.

After that, another bugle signal, the Rouse, "wake up" in German, known by many people as Reveille (French), is played.

"After they play the Last Post in respect to the soldier's death, then they play the Rouse for his awakening in the next life," Rooks explained.

The bugle calls were means of communication; they woke soldiers up and informed the commanders about the situation at the camp. There were special calls for meals and other routines, as well as for military actions. But music, in general, was also always a big part of the military be it battlefield or ceremonies.

"A parade without music is just a drill," Rooks quoted a colonel he knew. "But when you put music in it, when it's a big parade, they stand straighter, march smarter, it's just that much better, because music brings more life to the situation."

Canadian and British military always had brass and pipe bands. Back in the day, the bands would play in action restoring soldiers' morale.

"The last to that was World War One when pipers played in action," Rooks said. "Quite often they were the first ones to jump up and start piping to give the troops a little more encouragement. And they weren't necessarily protected."

But pipers back then were soldiers first. Rooks recalled the history of the Edmonton pipe band, which joined the Princess Patricia Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI) in 1914 and piped the PPCLI to France and back. The original duties of the bandsmen were treacherous, unarmed pipers playing were the first over the top, as they did in the leading wave at Vimy Ridge on Easter Monday in 1917, and later, at the conclusion of the battle, the men were sent, again unarmed, into no man's land to retrieve the wounded and dead.

Besides, pipers, who knew Gaelic, Scottish language which Germans didn't know, were delivering messages between the frontlines and the headquarters, so the enemy couldn't intercept the communication. They were also used as runners and carriers. But they still were musicians.

"The importance of music, it goes way back. They figured drums were the first things used in the army to send messages. And then after a while came bugles, then pipes," Rooks said, adding that the drum and pipes bands appeared in the military as well.

The PPCLI pipe band led the regiment through the streets of Ottawa on March 19, 1919, upon their return to Canada. They were demobilized the following day along with the regiment.

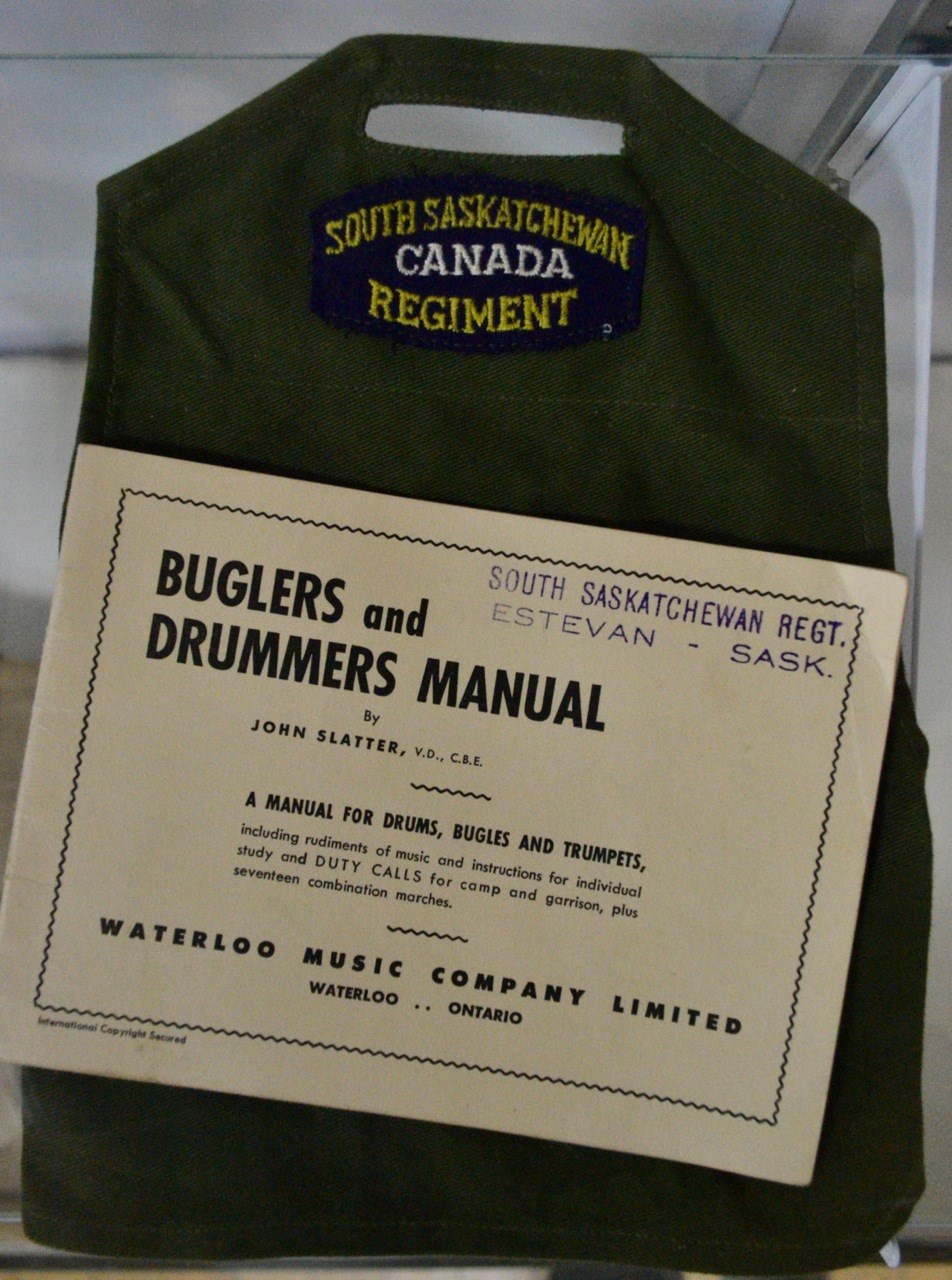

The 2901 Estevan (Elks) PPCLI Army Cadet Corps Pipes and Drums Band is descended from that band and thus wears a full Highland kit and Hunting Stewart tartan. They were formed in 1976 and Rooks, who had been a bugle player when he was a part of the South Saskatchewan Regiment prior to its being stood down, recalled how he had to learn from several great pipers to later start teaching young musicians.

The Estevan (Elks) PPCLI Army Cadet Corps Pipes and Drums Band usually participates in the Remembrance Day ceremony. But since they fall under the Department of National Defence and are currently restricted from holding any music training, they won't be at the cenotaph on Nov. 11. Rooks said that Angela Durr, who is a part of a civilian band, is planned to play at the ceremony as a piper, so that music, often an unnoticed but essential part of all military ceremonies, would still be a part of the Estevan's Remembrance Day.