WEBB, Sask. — How did a pioneer family with no farming experience find the courage to gamble everything on an uncertain new life as homesteaders in Western Canada?

“I tried to look cheerful when we got off the train, and when he bought the wagon,” said Liza Greer about her husband, Dan, as they slowly travelled with their two children across the Saskatchewan prairie to the unbroken land they would have to turn into a farm.

“Now, I was really frightened. What were we doing here, a clerk and his wife in their city clothes?”

The fictional couple from Montreal are the focus of Drylanders, the first feature-length fiction movie in English made by the National Film Board of Canada. It can be viewed for free online as part of this month’s Perspectives from the Prairies, a year-long collaboration between the board and The Western Producer that celebrates the newspaper’s 100th anniversary.

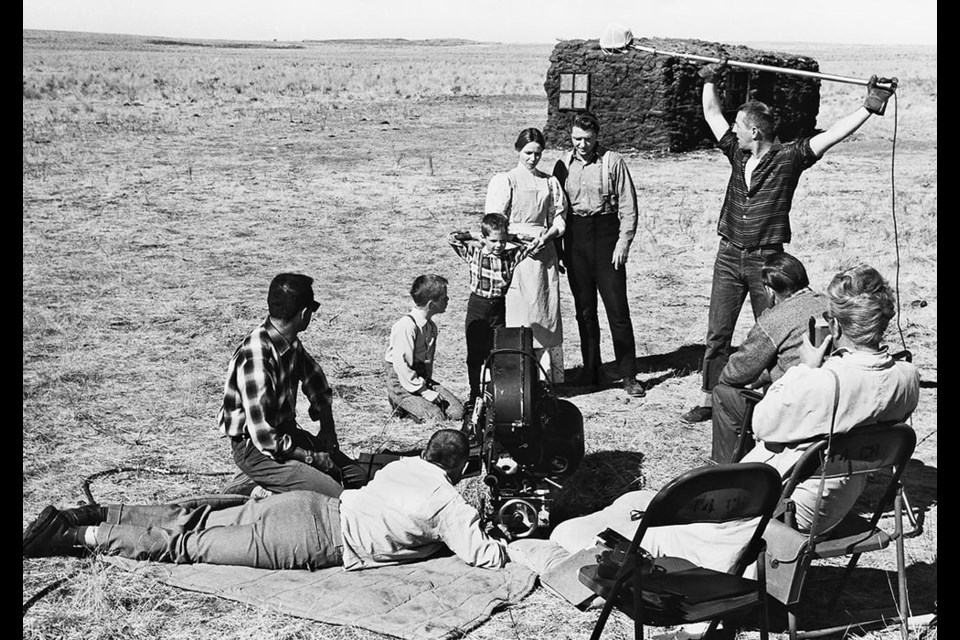

Liza was played by the late actor Frances Hyland, a member of the Order of Canada who was born in Shaunavon, Sask. Drylanders was mostly shot on location in 1961 in the Swift Current area, where it premiered in that city in 1963.

The movie is regarded as one of the top 10 films ever made by the NFB, said collection curator Camilo Martin-Florez.

It is not only praised for its cinematography and soundtrack, but also for its realistic portrayal of pioneer farm life from 1907 to 1938 by a cast that included local people.

One of them was the late Blake Thierman, who was part of a threshing crew depicted in the film, said his son, Kurt. Much of the movie was shot on the family’s farm near Webb, southwest of Swift Current, which included a two-storey wooden farmhouse that is still standing.

Kurt said the film’s depiction of the struggles faced by the Greer family mirrored some of the difficulties his own paternal and maternal grandparents had to overcome as they slowly built their farms in a vast and sometimes unforgiving prairie landscape.

“It was a hell of a lot of work, and can you imagine packing your wife up on a wagon, and a team of oxen pulling this wagon, and you don’t even know where (your land) is?”

Inexperienced newcomers like the Greers had to find their survey stakes in a country with no trees or roads, he said.

“And they said, ‘we’re here, we’re home, this is our farm.’ And there was nothing.”

Such pioneers were motivated by the promise, under the Dominion Lands Policy, of 160 acres for $10. However, each homesteader had to build a house, even if it was made of sod, and cultivate a certain amount of land within three years.

The back-breaking toil it took to turn empty prairie land into a farm, while raising children on whatever money the family could earn, was particularly hard on women. They often aged before their time in an era before indoor plumbing or rural electricity.

Household tasks such as laundry were done by hand by wives who also sewed their family’s clothes to save money. It is hard for people who use smartphones and the internet to imagine how much such women sometimes suffered from an intense sense of isolation and loneliness.

Many immigrant farm families didn’t speak English, and settlers preferred slow-moving horses or oxen to the early automobiles, which were regarded as too expensive and unreliable given the poor state of rural roads.

The nearest farm, let alone doctor, could be many kilometres away, and there were only occasional trips to the nearest community for supplies.

Kurt remembered the stories told by his maternal grandmother, who emigrated from Scotland with her husband. They left behind their relatives and friends, and letters or telegrams were the only form of long-distance communication.

“And they didn’t have much money when they came here,” said Kurt, who was about five years old when Drylanders was filmed. “Grandma said she was homesick and wanted to go home back to Scotland and stuff, but she stuck it out.”

Much of the movie is from the viewpoint of Liza, who provided the narration. As the Greers travel to what will be their farm, they meet another family returning to Minnesota after their sheep froze to death and their four-year-old son died of pneumonia.

“Dan, you’re a dreamer,” said Liza to her husband, who was played by the late Canadian actor James B. Douglas. “You saw those people this afternoon. They were farmers and they were beaten by this country. What chance have we got?”

Dan tells Liza it is his chance to be more than a second-grade clerk, and that there would also be opportunities for their children.

“It won’t be easy. I never said it would be.”

The family’s first crop of wheat was destroyed by hail, and Dan nearly froze to death in a blizzard while walking back to their sod house after getting food for his family from a neighbouring farm. However, Liza comes to believe in her husband’s dream as they eventually become prosperous enough to build a wooden farmhouse and own a car, celebrating their biggest harvest in 1928.

It would be their last in years due to the massive drought and dust storms of the Dirty Thirties, which occurred during the Great Depression after the stock market crashed in 1929. The film chronicles the deepening toll the impossible situation took on Dan and the family as his youngest son, now grown, is forced to ride the rails as a hobo in a fruitless search to find work.

“Dear mother, still no luck,” said Liza, as she reads a letter from her son. “Sometimes, it seems that the whole country is closing down. I’m still trying, but I’m beginning to think that nobody has a job for a farm boy.”

Many people lost their farms because they couldn’t pay their taxes, said Kurt. His own family had a spring on their land that provided about 27 gallons per minute of water for their livestock and vegetable gardens, helping their farm remain viable even if they had to trade potatoes for things the family needed.

The perseverance and fortitude it took to survive, but also the caution about spending money or dreaming too big, marked the character of many western Canadians for decades. It is hard for people who were born after agriculture started recovering in the 1940s to understand what it was really like.

Kurt said some young farmers in his area have never experienced drought. People need to have a tough skin to be a farmer, but it’s a good life, he added.

“We take a lot of things for granted around here that we get to see the sunrise in the morning and the sunset at nights and the stars. In the big cities, you don’t get to see that.”

Visit nfb.ca/channels/perspectives-from-the-prairies/ to watch Drylanders.

This column is part of a year-long collaboration between The Western Producer and the National Film Board of Canada celebrating the newspaper’s 100th anniversary.