Sometimes, things seem too good to be true.

Usually because they are.

Recently, an ad was placed in the News-Optimist, seeking secret shoppers to evaluate the services of certain businesses.

My editor clipped out the ad and dropped it on my desk, thinking it might make a good first person story. Turns out she was right.

I sent an inquiry to the e-mail address on the ad, [email protected], and waited for a reply.

The next day, I received an e-mail from Collins Maxwell, explaining the role of secret shoppers. The e-mail also informed me I would be paid "two hundred Canada Dollars" for every assignment. If I had a Spidey-sense, it would be screaming.

So I searched the Internet for CA Shoppers Crew Int. (which was the name of the company given in the email) and confirmed my guess: this was a hoax.

Curious to see how it would play out, I sent my name and work address as requested and waited for another reply.

In about 20 minutes, I received a reply, informing me that my "details were received and forwarded to our customer service. Through extensive background checks and processing, your application was approved."

I wonder what extensive background checks can be completed in 20 minutes?

The e-mail asked me to send them my schedule, so I informed them I could work at any time.

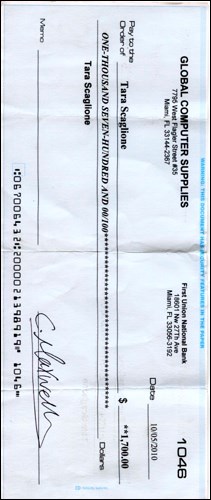

About two weeks after this, I received an e-mail informing me of my first "assignment." I would be evaluating "Wallmart" and Western Union. I had been sent a cheque for $1,700, of which $200 would be my payment for the assignment, $100 would cover costs (transportation/secret shopping) and $1,400 would be sent through Western Union to a "Javair Saulsberry," presumable to "test" Western Union's services.

So, I did a little "secret shopping" of my own. I went to the Cash Store to see if I could cash the cheque. They informed me I would have to get the cheque certified by a bank before they could cash it, which means the bank would check to see if the funds were available, effectively guaranteeing the cheque would clear.

I was fairly confident I knew what that would reveal.

But I still had a chat with Keith Kelloway, branch manager at the North Battleford Scotiabank, asking what would happen if someone deposited such a cheque into their account and tried to withdraw the funds. The answer was comforting.

"There's normally a hold put on cheques for six days," explained Kelloway.

He added customers, if credit-worthy, are able to add a cashback feature to their accounts that would enable them to withdraw a portion of the funds immediately, but these customers aren't typically ones who would fall for such a scam.

Kelloway said withholding the full amount of the cheque is beneficial for both the bank and customers.

"There are so many fraudulent cheques on the market," Kelloway said.

I soon received an urgent-sounding e-mail from the fraudsters, asking me to report on my assignment and provide the Western Union transaction number. I replied, saying the check had not cleared.

"Dear Tara," Maxwell wrote, "That is strange. Kindly tore the cheque. We will wire fund direct into your current account. Kindly send us complete informations of your current account. Thanks."

I sent them a series of random numbers. I didn't hear back from them.

Because the fraudulent company sent me the name and address of the person who would be collecting the funds on the other end, I wondered if they could be apprehended by police in the area, if a small amount were to be sent to them through Western Union.

So I called the FBI to float my idea past them. After being transferred to a million different departments and informed, "Ma'am do not engage with the criminals," I was asked to send an e-mail to their Internet fraud department.

I gave up. Clearly, the FBI has bigger fish to fry.

While all this was happening on my end, Maureen Charpentier in the advertising department discovered the payment had not gone through for the ad.

She sent them an e-mail, informing them the credit card number they provided wasn't working, and promptly received the same reply I did: sorry about that, give us your account information and we'll wire the funds.

There's not much that can be done about these types of frauds, as they are hidden by the obscurity of the Internet.

But while pondering the matter, I did consider one idea. If enough people set up a free e-mail account, sent a message to [email protected] requesting to be a secret shopper, and provided a mailing address somewhere in Canada (not necessarily real), it would seriously inconvenience the criminals.

Not that the average dollar it takes to send a letter to Canada would compare with the $1,400 they planned to scam people for, but if enough people did it, it would be a small payback. It would also show them Canadians don't make such easy targets.