MOOSE JAW — The federal government imposed the Chinese Exclusion Act on July 1, 1923, which negatively affected over 56,000 people nationwide, including Moose Jaw-based men like Sang (Charlie) Chow, Yow Yuk Yee and Wong Poy Jing.

Ottawa imposed the legislation to control the Chinese community and make it difficult for them to remain in Canada. This draconian law — a “humiliation,” as people called it — repressed and isolated people for almost a quarter century before the federal government lifted the Act in 1947.

Ottawa gave Chinese people one year to register — it was mandatory — and the first from Moose Jaw was Yee, 29, who worked as a cook at the Maple Leaf Restaurant on River Street West, according to his Chinese Immigration (C.I.44) information sheet.

Born in Hoi Ning, Canton, China, he arrived in Victoria, B.C. on Feb. 9, 1913, leaving behind a wife and infant son. He was forced to pay the $500 head tax to enter Canada, which Ottawa had imposed to restrict Chinese immigration.

Yee registered at the RCMP detachment in Regina on Oct. 11, 1923, with his certificate showing he was five-foot-six and had a burn mark above his right eye.

The oldest Chinese person from Moose Jaw to register was Jing, who was 67, lived at 160 River Street West and was a cook. He arrived in Canada on June 10, 1896, with one son in tow; he left behind a wife and four children.

He registered in Moose Jaw on May 27, 1924.

Chow, 48, arrived in Victoria on May 17, 1899, and later moved to Moose Jaw. He was married to a Romanian wife, Mary, while he worked at a restaurant at 128 River Street West and ran a small general store; he lived at 841 Coteau Street West.

Chow registered on March 14, 1924, while he waited until June 14, 1924 — 16 days before the deadline — to register his five children, including son Peter, 11. The adults received C.I.44 certificates, while Ottawa issued C.I.45 immigration cards to Canadian-born kids — the paper identities did not grant them legal status in Canada.

It was through Peter that Charlie became the great-grandfather of Darin and David Chow, who sit as judges in Moose Jaw.

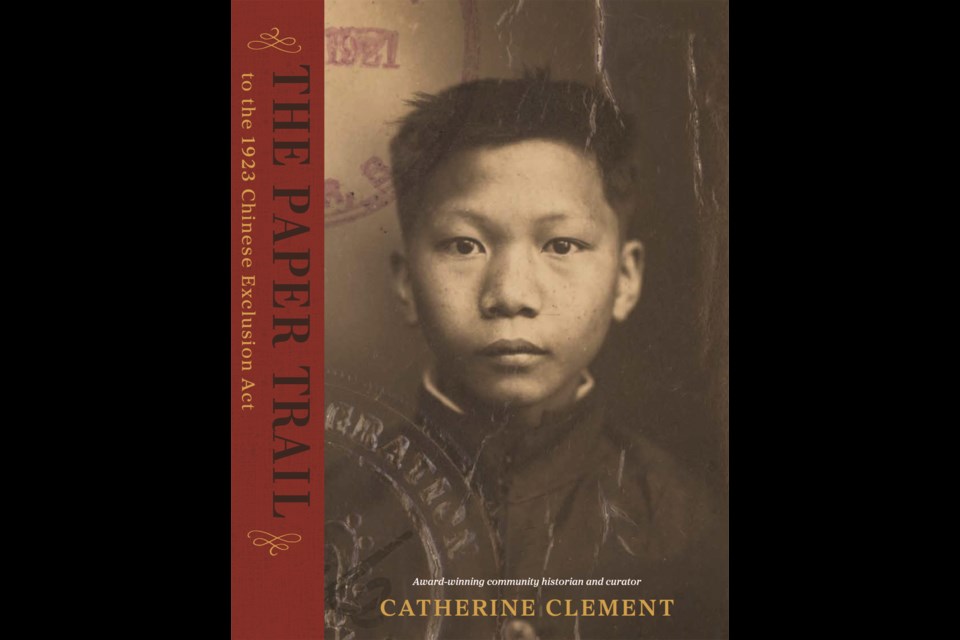

Chow, Yee and Jing were just some interesting people whom author Catherine Clement discovered while researching the topic and who are included in her new book “The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act.”

Clement will be at the library’s performing arts theatre on Thursday, July 24, discussing the book from 2 to 3:30 p.m. and 6:30 to 8 p.m.; attendance is free.

A poorly understood story

“It’s the least well-known story … (in) Canadian history, even amongst the community it most affected,” Clement stated during an interview.

Chinese people were the most heavily documented and surveilled immigrant group ever in Canada, based on information from Library and Archives Canada (LAC), she said.

Furthermore, this was the first time in Canadian history that the government used mass photography to identify people, coming just 11 years after Ottawa first used photos — mugshots — for prisoners at the Kingston Penitentiary.

“… for immigration officers, the photographs became a way to distinguish people” because most Chinese men looked alike, said Clement.

The “silver lining” with the photographs is that they bring to life the certificates and registration forms and let viewers see the subjects and whether they are wearing cultural clothing or Western clothing, she continued.

Meanwhile, the “irony” of the situation is that while the Chinese community hated the certificates and destroyed most of them afterward, the remaining documents created an immense “paper trail” that helped Clement tell this story.

She noted that knowledge about this topic was lost in a single generation after the Act was repealed because Chinese people wanted to forget it, move on and integrate into society after receiving their citizenship. Therefore, they never told their children or grandchildren about their experiences.

Hard numbers

Of the more than 56,000 Chinese people who registered in Canada, roughly 1,300 were adult females, the researcher found. Most were men who had spent 30 to 50 years living here but couldn’t bring their wives and kids because of the 1885 head tax.

In Moose Jaw, 431 people registered, with only 14 of them female. Forty children under age 18 were also registered, and while most were born in Canada, they received an immigration card under the Act.

Of those 431 people, roughly 250 men worked as waiters or cooks, while 72 worked as laundry cleaners.

The search begins

Clement went searching for the certificates but didn’t find any with Library and Archives Canada — although it did have the Chinese Immigration Service registration forms. LAC initially refused to provide the forms because of privacy concerns, but eventually released everything — over 56,000 JPEGs — after Clement found “influential people” to help.

Meanwhile, Clement travelled the country meeting families and photographing the certificates in their possession. When she asked them what their fathers or grandfathers had said about living during the exclusion years, almost 95 per cent of them knew nothing.

Unimaginable stories

Archival newspapers were critical in helping Clement fill in the gaps. She searched through Chinese and English publications looking “for a bread crumb” or a glimpse of what happened during the 24 years, while she also dug through court records and coroner’s reports.

“And, it turned out, in many cases, to be worse than I could have ever imagined,” the author remarked. “The silence buried so many things … . It was purposely done to not talk about it.”

Clement discovered many stories of “great despair,” including many men who committed suicide or were put in insane asylums. There were even men who had lived in Canada for decades and worked menial jobs, but just gave up on life.

Yet, there were also stories of resilience, especially about people living on the Prairies. Clement noted that she found stories that were “funny and quirky,” such as one woman who killed a skunk and fed it to her family since they had so little food.

“People did what they had to to survive,” she added.

‘Dark winter of exclusion’

Meanwhile, the registrations were nerve-wracking experiences for many people, Clement said. People disliked the mandatory registration not only because they faced an “interrogation” from the RCMP, but also because they had to register their Canadian-born children.

Clement said she felt frustrated learning about this topic, but became more forgiving as those affected told her why they remained silent for decades. She also realized that she wanted to honour these people for their “walk through the dark winter of exclusion.”

The author also pointed out that history is important and builds on the past, whether people like it or not. Moreover, this story illustrates how ethnic groups can contribute to society when given the chance to thrive.

Clement added that once Chinese people gained citizenship and entered professions that were once closed to them, they became “a model minority.”

Visit plumleafpress.com for information about Catherine Clement and “The Paper Trail.”