More than 250 years ago European mapmakers pasted maps onto wood and cut them into small pieces that could be pieced back together. As a result, jigsaw puzzles were born. Two and a half centuries later these “dissected maps” have become educational and entertainment tools for some, and a bit of a passion for others.

Miss Mahoney, grade one teacher at Outlook Elementary School, has puzzles of varying size and difficulty in her classroom. Some are used for specific purposes such as completing a 100-piece jigsaw on 100 Day, while others are options for students during down time or when recess is indoors. Like many educators, Mahoney believes there are benefits to be gained by having students work on puzzles. “I think it promotes problem solving,” she said, as well as “grit—having kids stick with a task, and cooperation, as they often work with a friend on a puzzle.”

That element of cooperation is on display at Outlook High School where students stop by the library to work on puzzles, in an initiative that has proven to be quite popular. Librarian Marla Ziegler was looking for fresh ideas that could be implemented on a small budget, and decided to give jigsaws a try. What started as one donated puzzle “just kind of snowballed” and she now has a shelf full, which is a good thing since students are completing them at an average rate of one per week.

At different points throughout the day individuals or groups of students can be found gathered around the puzzle working toward its completion. “It’s a pretty consistent group in the morning,” Ziegler remarked, “ and a consistent group that comes in after lunch before heading to class. But throughout the day different ones come in and do a piece here and there, or when they come to pick out a library book they will also put in a puzzle piece or two.”

Dissectologists, the name given to those who enjoy what were originally dissected maps, experience benefits from assembling puzzles. Dopamine, which affects memory, concentration, motivation and stress levels, is released each time someone successfully puts pieces in place. Many offices have jigsaw and other puzzle games in their breakrooms because after working on these for a few minutes, employees come back feeling more refreshed. Ziegler points to that benefit in the school as well. “What I like about it,” she said, “is that they don’t even realize they’re using their brains. It’s a rest period. It’s not something begging them to engage like you have to in class so they come in here and it’s relaxing.”

That is certainly the experience of Cam and Dorianne Leslie who work on puzzles most evenings throughout the winter. Cam, the Maintenance Technician with Outlook Housing Authority, and Dorianne, a care aide with Home Care, are currently completing their 22nd puzzle since Thanksgiving. As soon as one is completed Cam will take a picture of it and they will begin another selected from their burgeoning shelves.

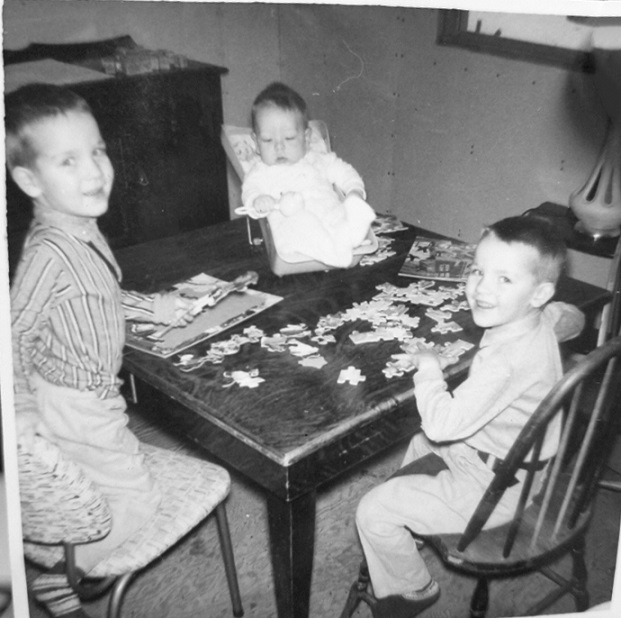

Cam has been doing puzzles since he was a child. “I’ve still got a couple of puzzles I had when I was around 10 or 11,” he remarked. “My favorite is a 500-piece Saturday Evening Post Norman Rockwell cover. I’ve done it many, many times.” So many, in fact, that he often claimed he could put it together in about 2 ½ hours. Two years ago he put that claim to the test and actually completed it in less than two hours. “I have all the pieces memorized,” he said with a smile.

About five years ago Dorianne joined Cam doing puzzles and though she struggled at first she has grown to enjoy the hobby very much. “I’ve learned some of the techniques that he uses,” she said, and is now better at matching colors in difficult sections or seeing emerging patterns. But she added, “He does this way better than I do. He gets to a certain point where he has all the pieces lined up in shapes. It looks like an army,” she added with a laugh. “

When puzzles were first produced for adults, they often came with no picture or title on the box so the assembler had the challenge of working without a guide. Today, puzzle aficionados have a huge range of complexities to provide similar challenges. From solid colors, to same-shaped pieces, to 3D versions, Cam has done them all, recently completing one he describes as the most difficult amongst them. “It was a total black one,” he explained. “Just solid black. On the box it said it was 1000+ pieces. It came with a map so at least you knew what shape they were but it was still very hard to find each piece. It’s the toughest one I’ve done.”

Puzzles on-line are a huge industry and although Cam does those as well, he prefers working around his kitchen table where there is always one on the go. “I need to have the feel of the pieces,” he said. “On my phone I can’t see enough of it, but here I can see all of it. I can look at all the pieces and find what I need.”

Kate, a grade 12 student who enjoys doing puzzles in the OHS library and at home, has a similar reflection. “You use your brain,” she said. “You have to think more in putting the pieces together rather than just swiping and clicking pictures.”

For any puzzler, one of the most frustrating things to encounter is a missing piece. So what do you do when that happens? Well, if you’re Cam Leslie you build replacements of course! To finish a 2000-piece Coca Cola puzzle which had two missing pieces, Cam used cardstock cut into 2-inch squares. After tracing and cutting out the shapes needed, he laminated cardstock together to replicate the required thickness and used whatever he could find to match the color as closely as possible. “It’s quite a disappointment when you work on a puzzle and you are missing a piece. I have to complete it to the point of even having to make my own pieces, just in case you give it to somebody else.”

The puzzles Cam and Dorianne do together also mean time spent together and that’s something they both appreciate. “When you finish a puzzle there’s a feeling of accomplishment,” Cam remarked. “Especially after you finish a challenging one like this one we’re doing now and you know it’s a team effort.”

This is one of the benefits Marla Ziegler sees happening in the library. “You’re still able to engage with people,” she said. “Often there are hushed conversations over the puzzle. I kind of feel like we’re losing our social skills so this is just another way to connect.”

.png;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)