On March 19, 1974, Myron Johnson departed from Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake, piloting a CF-104 fighter jet as part of a mission to test a newly installed cannon on the aircraft. It was about two o'clock in the afternoon when Johnson, 43 at the time, cleared the runway. The weather was clear and it seemed like just another flight for the air force veteran, who at the time had been a fighter pilot for over 20 years.

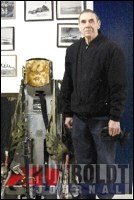

Of course, it would be anything but just another flight. Almost exactly 40 years after his plane fell out of the sky, the victim of a gun malfunction, Johnson donated the seat he ejected from to the Royal Canadian Legion museum in Humboldt. Sitting in the bed of his truck, the seat was old, heavy, and a bit worn, though still in quite good shape.

Johnson got his hands on it by virtue of knowing the grounds crew at CFB Cold Lake, who he often played hockey with in those days.

"A few days after the crash, they gave it to me," Johnson, now 73, says. "I don't know if it was against the rules or not."

Johnson's account of the crash that miraculously left him with no more than a bruised hip begins when he was making his third pass at a ground-based target (it was a live-fire exercise). A malfunction in the cannon caused a bullet to explode prematurely and sent shards of metal rushing into the engine, causing a nearly instantaneous stall and flameout. Johnson quickly recognized what had happened, ascended to about 1000 feet and tried to restart the engine three times. When that failed, and with the plane losing altitude quickly, the only remaining option was to eject.

"There was no time to be scared," Johnson says.

Between Johnson's legs was a yellow-and-black striped handle. He pulled it.

"It propels you about 300 feet above the aircraft," Johnson says. "At that point you detach from the seat and deploy your parachute."

The ejection had gone smoothly, but there was a problem: Johnson had been far too close to the ground for the parachute to slow him down enough for a safe landing. As he rushed toward a stand of spruce trees, Johnson angled his body to the side and braced for impact.

"I didn't want to mess up my nose," he now says with a laugh.

Of all the rules that Johnson followed during his ejection, it was one rule he didn't follow that might have saved him from serious injury or even death. Attached to Johnson as he rushed toward those spruce trees was a metal survival kit, a red box about the size of a couch cushion. Protocol dictated that the kit be detached from the pilot's body and trail behind on a lanyard. Johnson didn't have time to do that, so when he turned in the moment before impact, it was the survival kit that took the brunt of the blow.

"I fell into about four feet of snow and got right up," Johnson says. "A bit of a bruise on my side but other than that I was fine."

A trailing pilot had seen Johnson eject from his plane and immediately alerted the base. Within a few minutes a rescue helicopter arrived to pick Johnson up. He was flying again within a week.

Johnson was careful to downplay any heroic elements to his story.

"It's just something that happened to me," he says. "I made it through it and that's that. I don't want any fanfare or anything like that."

Johnson has been farming in the LeRoy area for the better part of 30 years, but recently decided to donate the seat from the plane to the museum.

"I'm downsizing and have nowhere for it anymore," he says.

For Rev. Al Hingley, who runs the Legion's museum, donations like this one are the kind that keeps the place going.

"Sometimes people think that once they've seen a museum that's all there is to it," Hingley says as Johnson backs up his truck, seat in tow, up to the museum's entrance. "What they forget is that a museum is a living organism. There's always something new to see."