Editor’s note: In August 2020 Shelley Luedtke visited Shiloh, the site of the first Black settlement in Saskatchewan. A story about that experience was published in the September 3 issue of The Outlook. Following its publication, we received the names of two descendants who live in this part of the province. She made contact with them and is proud to present their stories.

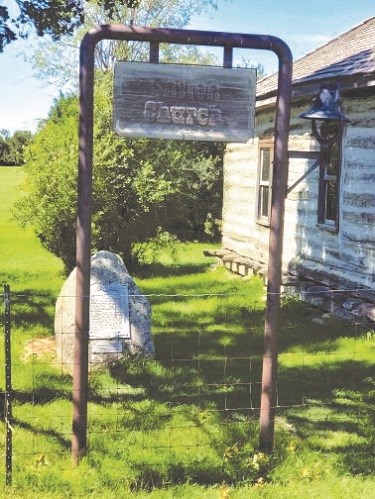

There are no big billboards drawing attention to its location. No gift shop that accompanies a tourist attraction. Then again, this is no tourist attraction. It is an historic site that holds the stories of Black families looking to escape segregation in Oklahoma in the early 1900s, and willing to see if this place called Saskatchewan could be a path to greater freedom and a brighter future. Its legacy lies not just in the land they settled 30 kilometres north of Maidstone, but in the testimonies of the descendants who continue to call Saskatchewan home.

Among those that came north were Joseph and Mattie Mayes who took on important leadership roles in the community that would come to be known as Shiloh. Their descendants include great granddaughter Dr. Charlotte Williams, a Veterinarian living in Elrose.

Williams, who was born and raised in North Battleford, has always been aware of what drew her ancestors to Saskatchewan. “My great grandparents, Joe and Mattie, and their ten children immigrated to Canada in 1910 to escape segregation laws that they saw as a form of re-enslavement,” she explained. “I think of all the freedoms that I enjoy because of the hard work and sacrifice it took to come to a new country.”

Eleven other families came from Oklahoma as well, representing about 75 individuals who arrived in the Eldon District, establishing homesteads in a region so different from what they left behind. Williams marvels at their courage to “leave the warm weather of the southern United States and endure the harshness of Saskatchewan” as a new settler.

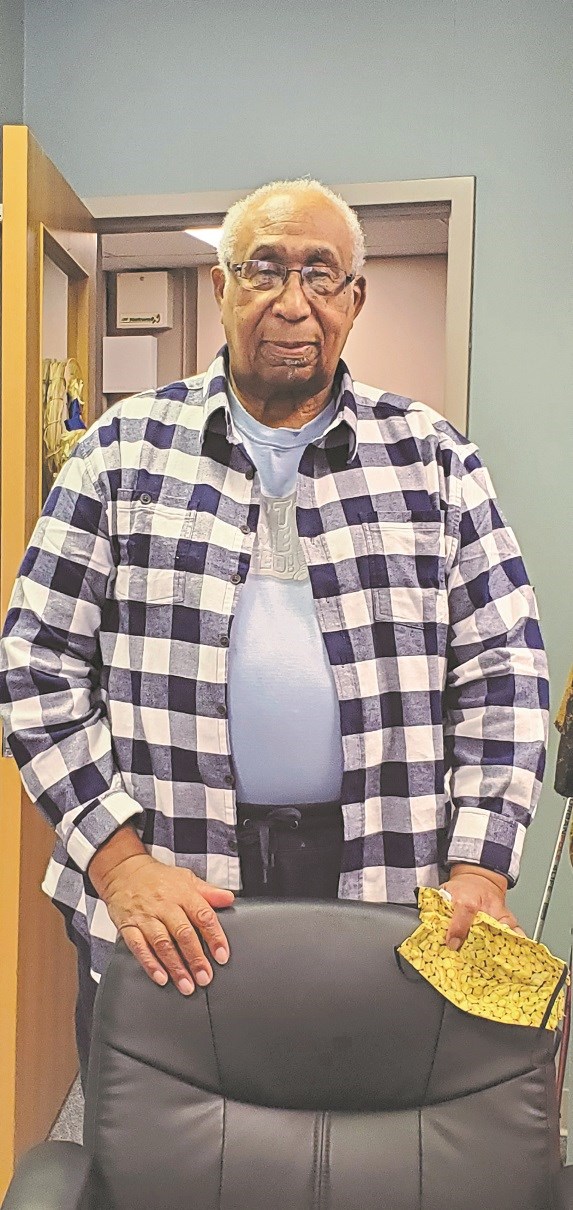

Elwood Mayes, a descendant who lives in Saskatoon, was part of another line of Mayes’ settlers, and he had the unique experience of living there himself as a child. “I was part of the Shiloh community when I was a kid,” the 87-year-old said. “I lived right on that settlement. That was the early ‘40s. I can’t remember who all was there but there were quite a few families living there at the time.”

Born in 1933, Mayes recalls helping out on the family farm as well as playing with other children at Shiloh. “When I was a kid there was a lot of kids running around. A lot of families there lived about a mile apart,” he explained, “one family on a quarter, another family on another quarter.”

Like all farm families, each member assisted where they could. “I was a little kid,” Mayes said, “but even at seven or eight years old, kids worked.” In the summer he was picking stones, and by age 11 was stooking sheaves.

At the heart of the new settlement was Shiloh Church, a building filled with Sunday School memories for Mayes, and a place of special connection for Williams. “My great grandfather Joe was a spiritual leader and pastored the church,” she explained. “It was the first building built as a gathering place for the new Black immigrants.”

When Williams was at Shiloh the day it was designated a heritage site, she marvelled at the effort it would have taken to get that church built. “When you sit in the pews and feel the texture of the mudded walls, you think of what they went through to build this gathering place, and are thankful,” she remarked.

The church was constructed of hand-hewn poplar logs hauled by ox cart from the North Saskatchewan River. The labor involved was matched by the care taken to build it, and it remains the only building still standing on the settlement. The other piece of the community that remains is the cemetery that sits nestled in a grove of trees just beyond the church. Among the individuals buried there is Elwood Mayes’ mother who passed away when he was quite young. The cemetery sits on what is still his grandfather’s property.

In the early 1930s Shiloh was a prosperous community, growing to as many as 75 families. But following the Great Depression people started leaving and by the 1950s only a handful of Black families remained in the area.

Elwood Mayes’ family was among those who sought opportunities elsewhere. “I was 16 when I left Maidstone,” he explained. “My family left, and then others, too. Then there were not that many families left.”

Mayes moved out on his own, was employed with the railway, and then worked construction for 32 years. He lived in Alberta and BC, raised a family and then returned to Saskatchewan two years ago to be closer to his sons. He has been back to Shiloh to help with clean-up efforts and mark graves with crosses, but his most recent visit occurred at the ceremony marking its designation as a heritage site in August 2019. “Visiting it at the unveiling was so much different than when we went to clean it up,” he shared. “I’d been away so long but this was a chance to take some of my grandkids out there. They were really proud to be there.”

It was an event that drew descendants from across the country and south of the border. “A lot of the Mayes family showed up there,” he remarked. “There was family I’d never met before because we are all scattered across Canada and the U.S.” But it also gave him pause as he looked at all the dignitaries gathered that day. “All the mayors of all the little towns were there. I couldn’t help wonder where they were when we were growing up. It was hard to put it all in perspective.”

It’s something the residents of Shiloh dealt with as they established the community, and something their descendants still deal with today: racism. Mayes said, “It was pretty rough at times. A lot of White people didn’t want the Black people there. We used to have fights in school because someone would come along and call us that ‘n’ word. My dad would become the mediator when there was trouble. We’d call him in to settle things down when we were growing up.”

Yet he notes it wasn’t just his community experiencing this, but other ethnic groups as well. “A lot of racism was against other groups, too. People were against them for some reason. But the racism? Yes, it was there. But I tell you what, I don’t think it was near as bad as what you saw in the States last year and the year before. Nothing like that.”

He also points out not everyone held discriminatory attitudes. “My family got to be good friends with some of the families in the area. They were very good people and we made friends.” He also takes an optimistic tone when it comes to his own family. “Of course it is much, much better for my children and grandchildren.”

Charlotte Williams credits her family with helping her confront racial challenges. “Lately it is a question I have had to ponder a lot,” she admitted. “I grew up in a community with very few Black people but my parents kept us so involved with community I did not feel different. If I experienced racism, I never dwelled on it, it never impeded my path. My parents taught me to walk around it or over top of it, but just to put it behind me.”

Nonetheless, the woman who blazed trails in the world of Veterinary Medicine has had to be prepared for all sorts of encounters. “When people meet me for the first time, they ask what country I am from,” she said. “Then I have to explain to them that my family likely immigrated before, or at least the same time, as their ancestors.”

With her own children, she took the lead from her upbringing. “We as parents did what my parents did to make sure they got involved.” It is reflective of the approach her ancestors Joseph and Mattie also took when they first came to Canada. “My great grandparents were spiritual people. They were community people,” Williams remarked. “My great grandparent Mattie was a midwife and helped the community with herbal remedies until the doctor arrived. They shared their food and skills with the entire community, not just the Black people. They understood if they were to survive, they had to work together. I want my children to understand it is important to be tolerant, work hard, be kind and to pray.”

Inside the Shiloh Church sits a guest book inviting visitors to make note of having stopped in and taken time to consider this important piece of the province’s history. “People from all over the world have signed it,” Mayes says with pride. He knows it means their stories are being told the world over. “When people find out I’m a Mayes, they want to talk,” he said. He is more than pleased to do so.

Perhaps that is the greatest legacy of the Shiloh community. Not in future billboards announcing its location, but in the stories of the original settlers and their descendants, in lives well-lived.