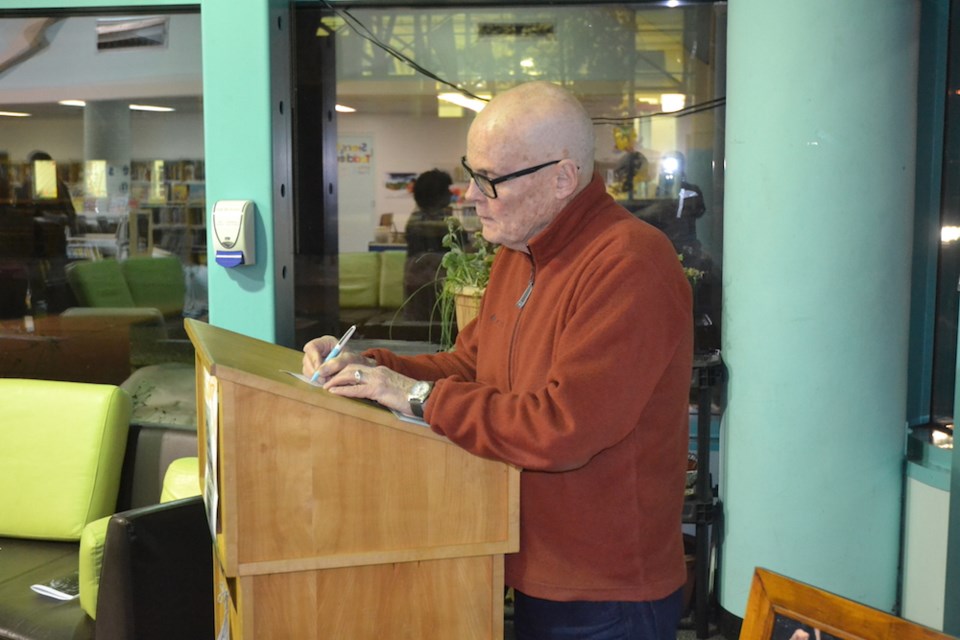

The Estevan Public Library hosted a conversation on the many traumas of residential schools and one man’s resiliency against it, when author David Carpenter paid a visit on March 2. Carpenter visited to share the story behind The Education of Augie Merasty and to sign copies of the memoir.

The Education of Augie Merasty is the product of a collaboration between Carpenter and the late Augie Merasty, a Cree trapper who lived in northern Saskatchewan and was a survivor of the residential school system and the abuses it entailed.

Although Merasty recently died, his legacy lives on in a series of stories that are entailed within the Education of Augie Merasty. Carpenter explained to guests that the accounts in the book were written by Merasty himself, while Carpenter edited and compiled them into the format of a book. The anecdotes and stories were sent by mail to Carpenter, who is a writer and professor who used to teach in Saskatchewan’s far north. Merasty sought Carpenter out, looking for someone to help tell his story.

Much of the writing Merasty did, he did at a cabin in the far north of the province, in a remote area called Birch Portage. Carpenter said the time Merasty spent writing in the far north was an escape for him. In the seclusion of the far rural north, Merasty devoted himself to the task of writing. Merasty struggled with a drinking problem and preferred the quiet of rural life in the north, to life in the city.

Merasty’s writing was focused on his experiences as a child at the St. Therese Residential School between 1935 and 1944. Merasty’s accounts covered every aspect of life in those years, from the steady efforts to assimilate the young Merasty and many like him, as well as the physical and sexual abuse he and the other aboriginal children faced at the hands of those in charge of the school.

Although a troubled, complex man, there is an undercurrent of defiant optimism in Merasty’s writing about his own life. This is present in descriptions of how he and his friends made the best of things, despite the awful way they were treated.

Carpenter said that in all his editing of Merasty’s writing, he made a deliberate effort not to edit out any of the latter’s writing voice. He noted that Merasty’s vivid personality shone through in his writing, adding “Augie could go, in two paragraphs, from abject despair to uplifting joy.”

Carpenter spoke reverently about the courage of Merasty, in talking about the abuse and indignities he’d experienced while at a residential school. Carpenter said that he believed Merasty’s sharing of his story had a redemptive effect on him, helping him “exorcise ghosts of his past.”

“As a kid, I was interested in heroes, whether they were superheroes or sports heroes, but I never met a hero until I met Augie,” said Carpenter. “It took amazing courage to revisit the nightmare of his childhood, and admit he was assaulted and abused.”

There has been some controversy afoot relating to The Education of Augie Merasty, with some Canadian schools allegedly refusing to include the book in their curriculums.

While he acknowledged that he had heard about some schools not wanting to include the book in their curriculums, Merasty said, “I’ve only heard about one school that don’t want it taught, but I’ve also heard that it isn’t going to be taught at that school because it wasn’t sent to a committee that decides which books are read to students.

“I haven’t seen any evidence of censorship on this long tour of mine. I’ll find out as I go, but so far, there has been no evidence.”