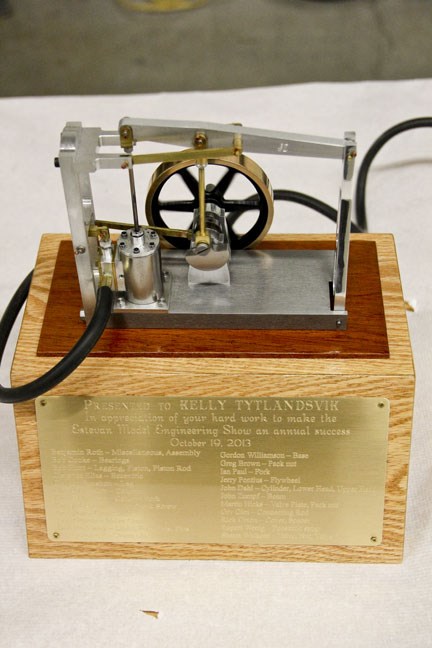

For 26 years, Kelly Tytlandsvik has been hosting a model engineering show in the Energy City, and after 26 years, many of his regular exhibitors decided to give something back.

On Oct. 19, Day One of this year's show, a group of 26 model engine enthusiasts presented Tytlandsvik with a small engine built collectively by the group. An e-mail was circulated in February with the idea of everyone building one piece and sending it to Benjamin Roth who assembled each piece into the final running engine.

This year's event at the Wylie-Mitchell Building featured 221 engines displayed by 55 exhibitors.

One such exhibitor was Rich Carlstedt, a 74-year-old retired mechanical engineer from Green Bay, Wis. Carlstedt showed off two engines of particular significance to the history books, Matthew Murray's steam powered hypocycloidal pumping engine from 1802 and a replica of the 1862 steam engine in the USS Monitor, the first all-iron ship ever built.

Murray's hypocycloidal pumping engine now resides in the Henry Ford Museum, and that's where Carlstedt got the basis for his model. Carlstedt noted that Murray was a British engineer and tool manufacturer but is largely lost to history because of a possible smear campaign by James Watt, who had his own steam engine.

He said the two warred with each other, but Watt had more money behind him, bought all the land around Murray's plant so he couldn't expand and sent spies into his professional enemy's factory.

Carlstedt first visited the Henry Ford Museum and saw the engine in 1972.

"I was just blown away by the technology of a 200-year-old engine. The pump on the engine was very complicated, but it was a one-piece casting. That to me is just incredible, because this would be difficult to cast today," said Carlstedt.

When he builds his models he does a lot of research to learn what technology is behind the real engine.

"What I discovered was fabulous," he said. "Matthew Murray, in 1802, patented the hypocycloidal motion, which was taking linear motion and converting it to rotary."

On the engine, the gear travels around clockwise, converting the motion of the piston from the steam cylinder into a rotary motion, which then operates two pumps.

"In this engine you have the invention of the D-valve. The D-valve was a very small valve arrangement, and it's used to this day."

He said the D-valve had a number of advantages over the Murdoch valve that was commonly used at the time, most noticeably, size.

Another part of historical note on the engine is the first tapered bearing, which Murray patented in 1802. Carlstedt said the bearing was fully adjustable, and mechanics could tighten the nuts in order to draw the bearing in to take up any clearance.

"On this engine, we've got the tapered bearing, the hypocycloidal motion and the D-valve that are all earth-shaking inventions," said Carlstedt. "Its a unique engine, in it's historical application, because of what it produced. It would be like having a laptop computer or an iPod if you had it 30 years ago, that's how advanced it was. This was considered so technologically advanced that they didn't consider it a contribution to the Industrial Revolution."

His model he called unusual because it's all steel and cast iron. There is no plating or stainless on any of the pieces.

It's all bare metal, so he has to keep it somewhat climate controlled. The humidity and the touch of a person's oily fingers could lead to rust build up.

"It took many hours of polishing in order to produce that," he said.

His mentor passed away just before Carlstedt started work on the engine and he remembered being told, "the problem with paint is that it covers the beauty of iron," and that's when he decided not to paint any pieces on the engine.

"The majority of the parts I finished were of such high polish because I was trying to emulate the quality that (my mentor) did. He was just such a fabulous craftsman, and I wound up building the entire engine, dedicating it to his memory and not painting any part of it."

It took Carlstedt about two years to build the model, and about 1,500 hours of work. It cost $50 in raw material, but $300 in polishing supplies as he went though two Dremel tools while polishing each piece of cast iron.

After building the model engine of the warship, Carlstedt is still involved with the Monitor, as he is writing a book on the engine of the Civil War warship, which would eventually sink on New Year's Eve in 1862 off the coast of Cape Hatteras, N.C. The wreck was later found in 1973.

Carlstedt said he has 10 years of research into the model engine, which he doesn't call a model.

"It's really a miniature replica, because all of the internal parts are also machined to the same detail," said Carlstedt, who is helping the Smithsonian Museum restore the original engine.

He began work on the engine with little to go from in terms of visual representations. He was given a photocopy of the design, which had been photocopied a number of times previously and was little more than faint strokes on a piece of paper covered in oil splotches.

From that copy, he carefully connected the dots until he had a reasonable blueprint to draw from. It took him seven years to complete the replica that was scratch built from solid materials. At one-sixteenth scale, all components inside the engine are built to scale as well. The smallest parts are 17 iron keys used in various shaft fittings that measure .030 by .030 by .076 inches long.

Carlstedt called himself a little "nuts" when it comes to his attention to detail. Along with the minute interior on the Monitor, he researched what kind of bricks were used as a base for Murray's hypocycloidal pumping engine.

He found they were "blue bricks," which are uneven leftovers that wouldn't have been suitable for building. The exhibitors at the Model Engineering Show don't really believe in something that can't be useful.

For people like Carlstedt, and Murray long before him, they can turn anything into something.